Did Lucy Foster run a Tavern?

The story of Lucy Foster has always intrigued me. Born in 1767, Lucy Foster was initially a black slave to Job and Hannah Foster. Later, she gained her freedom and lived independently. In 1945, two archaeologists, Adelaide and Ripley Bullen, stumbled upon her homestead while searching for a Native American site. To their surprise, they discovered the 19th-century home of a freed black woman.

The subsequent archaeological dig revealed a wealth of information, including thousands of objects, a house foundation, well, garden, and dump on a one-acre lot. In 2018, the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) showcased these objects as part of the Slavery and Freedom exhibit, on loan from The Peabody, The Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology of Andover, MA.

The site earned the name "Black Lucy’s Garden" from a newspaper article in 1863. However, I prefer to refer to it as Lucy Foster’s Homestead. I believe she deserves recognition beyond being identified by her race and a garden. Lucy Foster led a full life, yet numerous questions remain unanswered. What was her life like? How did she support herself? What do these discovered objects tell us about her life?

With over 2000 shards found on the site, many wonder if Lucy Foster was involved in running a tavern or providing hospitality services. Over the last 80 years, others have examined Lucy Foster’s Homestead in an attempt to unravel the mysteries of her life. I aim to take a fresh perspective on her story, particularly exploring the possibility that she ran a tavern.

Who was Lucy Foster?

In 1767, Lucy became a part of Job and Hannah Foster’s household as a black slave. At that time, the Fosters had a 5-year-old son named Joseph and had recently acquired an indentured servant, a white girl named Sarah Gilbert. Lucy and Sarah were baptized together at South Parish Church in 1771 when Lucy was just 4 years old. The Fosters welcomed their second child, Mary, on Feb. 5, 1775, making Lucy and Sarah vital helpers in the household. Genealogy records indicate that Job and Hannah had only two children, possibly explaining the addition of two helpers.

The Fosters owned land on both sides of Woburn Street, known for many years as the Way to Boston. Job inherited “land, dwelling, barn, and corn-barn” from his father, Joseph, in 1751. The disbursement of the land led to the establishment of the Ballard Tavern (1771-1798). The Ballard Tavern absorbed the earlier Chandler’s Horseshoe Tavern (1690-~1715), as the Ballard's likely incorporated the old house and tavern into a newer structure.

Job's mother, Deliverance Dane Foster, lived with him until her passing in 1754, after which Job gained full access to the home. Job married Hannah Ford in 1760 at the age of 34.

During the mid-1700s, travel primarily involved horses or walking, with frequent stops for those on the road. Between the closure of the Horseshoe Tavern in 1715 and the opening of the Ballard Tavern in 1771, travelers likely paused for refreshments even without a tavern sign. The Abbot Tavern in town serves as an example, where people would stop for a rest regardless of signage. When the Ballard Tavern displayed the Black Horse Tavern sign in 1771, it likely became a bustling spot for travelers and soldiers.

Details about the operational aspects of the Ballard Tavern, such as the source of their liquor, remain unclear. Rum probably came from local distilleries like those in Boston or Haverhill, while beer, often made by women at home, was more localized. Well into the 1800s, cookbooks provided detailed descriptions of brewing beer, considered a task traditionally undertaken by women over an open fire.

Hannah, Lucy, and Sarah took charge of all domestic chores until Mary was old enough to contribute. These tasks encompassed cooking, cleaning, tending to livestock, butchering, gardening, sewing/needlework, and providing beverages. Common drinks included brandy, wine, beer, or cider, which were not only for family consumption but also for sale, with cookbooks offering a plethora of beverage recipes. Women often engaged in bartering, especially trading beer, to support family finances.

By 1750, Rhode Island prohibited the sale, trucking, bartering, or exchange of liquor with any Indian, mulatto, or Negro servant or slave. Massachusetts later enacted a more stringent law applicable to free minors and slaves, imposing fines for violations. Violations were punishable by a fine of four pounds with one-third going to the informer, the remainder to the collector of excise.

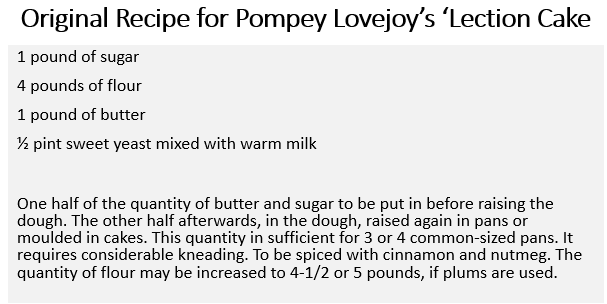

While Lucy might not have been allowed to drink at the Ballard Tavern, she could have been involved in making and delivering beer to the establishment, potentially serving as a helper at the tavern. Similar opportunities arose for black residents like Salem Poor (see Salem Poor: Colonial War Hero), who likely worked at the Poor Tavern, and Pompey Lovejoy, known for making and selling root and ginger beer and 'lection cake’ during town meetings.

Taverns and liquor became avenues for black individuals to earn money. In 1789, Massachusetts passed a bill to "Encourage the manufacture & consumption of strong beer, ale & other malt liquors," favoring locally grown grains over the expensive import of molasses required for rum. Breweries and homemade beer production thrived.

In 1782, Job Foster passed away, and his son, Joseph, inherited the property at the age of 20, becoming the man of the house. Hannah received the widow's half of the property until her remarriage, at which point Joseph gained full ownership. Hannah Foster now found herself caring for three children: Lucy (15), Sarah Gilbert (~15, possibly out of the household), and Mary (7).

The next year, Massachusetts emancipated all slaves, although many chose to remain with their masters. Lucy, at 16 in 1783, likely stayed with the Fosters during this time.

In 1789, Hannah Ford Foster married Philemon Chandler, and Joseph inherited the entire property as Hannah moved out. Lucy, now 22, seemed to choose to stay in the Foster's home. Joseph, at 27 and still unmarried, continued to share the household. In 1791, Lucy received a "warning out" notice, a town decision determining responsibility for her if she couldn't support herself. As a freed woman, Lucy, likely pregnant, was under the town's care for potential financial support.

On Oct. 20, 1792, Lucy's son Peter was baptized, with no record of the father. Joseph Foster, residing in the house, later married Mary Frye, having no children. The absence of marriage and father records added to Lucy's challenges in a society when having a child out of wedlock was frowned upon.

After Philemon Chandler's death in 1798, Hannah became a widow once again. Philemon bequeathed Hannah “$610.16, plus flax, wool, soap, cyder, apples, and the right to remain in his dwelling house for one year after his death”. Hannah likely moved back to live with her son, Joseph, until her death in 1812. We don’t know where Lucy Foster lives, but in 1800 and again in 1810 census, the Foster’s home has two “freed people” living there. It is likely they are Lucy and her son, Peter, but those details are not captured.

Upon the passing of Hannah Ford Foster Chandler, her will revealed a touching gesture towards Lucy Foster, stating, “I give and bequest to Lucy Foster, the Black girl who lives with me… a cow. I also give to said Lucy one acre of land.” Lucy received $126.15 from Hannah’s estate; the most substantial sum distributed. With this money and the one acre of land, Lucy embarked on the journey of building her own home.

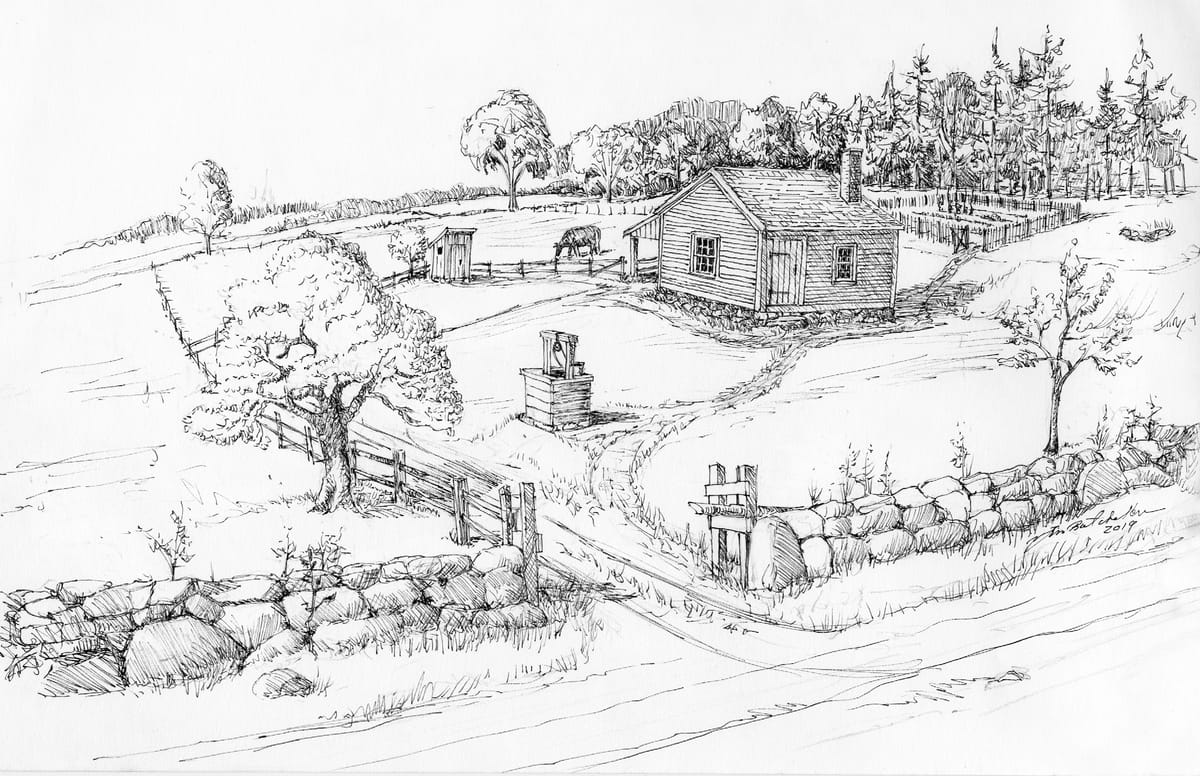

In an 1863 newspaper article, Alfred Poor described Lucy's dwelling. He mentioned, "When we get nearly over the plain, we pass by the road that leads through the woods over the Chandler Bridge and the river street. As we leave the plain, a sandbank is called Black Lucy’s Garden, named after a colored woman who once had a cottage between this and the meadow on an acre of land bequeathed to her by Widow Chandler." Captain Joshua Ballard played a significant role, gathering additional support from her friends to construct her cottage around 1815. In total the cottage costed $150 to build. Lucy resided there for about 30 years.

While constructing the cabin, Joshua Ballard assisted, and others contributed to the funds. Although there are no records of her son Peter, who would be 21 at this point, Lucy Foster began her independent journey. From her early years on her own, Lucy received assistance from the South Parish Church Fund, starting in 1813 (the year after Hannah’s passing) until her death in 1845. In 1827, at the age of 60, Lucy became eligible for firewood and supplies from the Overseers of the Poor, a service she continued to receive until her passing. The Overseers of the Poor aimed to support those in need while encouraging them to remain in their own homes. Lucy's neighbors, including Thomas Manning, Capt. Stephen Abbot, and Capt. Joshua Ballard, kindly delivered firewood and supplies, receiving a small sum of $97.70 over 18 years for their assistance.

Why did Joshua Ballard help Lucy get started?

The Ballard's considered Lucy not just a neighbor but a valued friend who deserved their support, especially considering Joshua's role as the executor of Hannah’s estate. Lucy's funds, totaling $150 ($126.15 from the estate and an additional $23.85), hold an approximate value of $3,655 today. This sum, though modest, was just enough for Lucy to construct what we would now call a “tiny house.” Her new cabin, measuring 12 feet by 12 feet, truly epitomized the concept of a tiny house.

From 1813 until her passing in 1845—spanning 32 years—Lucy Foster managed to navigate life on her own, teetering on the edge of financial hardship but avoiding destitution. This accomplishment is noteworthy for anyone, and particularly remarkable for a freed woman of color living independently, yet not entirely alone.

Lucy spent her entire life on Woburn Street, the Way to Boston, on land owned by multiple generations of Fosters. Her location ensured a constant flow of visitors traveling along the road. Lucy was not just a church member, but also a neighbor, mother, and a freed woman remembered in her master’s will. At times, others stepped in to lend a helping hand. While Andover had other freed persons of color like Salem Poor and Pompey Lovejoy, it was Lucy's white neighbors who prominently offered assistance. While race played a role in colonial Andover, with specific church seating and restrictions in taverns, Lucy's life was marked by the support she received—perhaps earned through her hard work, independence, and good nature.

Although there were other persons of color in her life, Lucy's narrative is one of collaboration and assistance from her community. While we may never know the true motivations behind these acts of kindness, I like to believe that Lucy earned the respect and support she received throughout her life.

Please join me next week for part two of the Lucy Foster story. I will explore the artifacts found on her property to better understand her life. Was she a tavernkeeper? Did she serve guests? How did she survive for 30 years in a small house on her own? The items found on her property begin to help us understand her life.

Sources

Andover Center for History and Culture, write-ups and photos of Locke Tavern, https://www.andoverhistorical.org/.

Andover Historic Preservation Site, write-ups and photos of Locke Tavern, Welcome to the Andover Historic Preservation Web Site | Andover Historic Preservation (mhl.org).

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Baker, Vernon, Historical Archaeology at Black Lucy's Garden: Ceramics from the Site of a Nineteenth Century Afro-American, Phillips Academy Andover, The Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology, 1978.

Greene, Lorenzo J., Slave-Holding New England and Its Awakening, The Journal of Negro History, Oct. 1928, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Oct., 1928), pp. 492- 533, 1928.

Martin, Anthony, Homeplace Is also Workplace: Another Look at Lucy Foster in Andover, Massachusetts, Published online: 18 January 2018 # Society for Historical Archaeology 2018.

Mofford, Juliet Haines, Andover Massachusetts, Historical Selections from Four Centuries, Merrimack Valley Preservation Press, 2004.

Comments ()