Rum and the Revolution

When I began delving into the history of the Molasses and Sugar Acts of the 1700s through the lens of taverns, I gained a newfound appreciation for the significance of molasses and rum in the events leading up to the Revolution. It's intriguing how our education primarily focused on the "taxation without representation" aspect, neglecting the profound impact of the rum trade and its associated issues like alcoholism and economic consequences. Boston, boasting an impressive array of 38 rum distilleries, a bustling shipping trade, and a population reliant on rum, had no choice but to respond with outrage.

The sprawling rum supply chain had a far-reaching influence, intricately intertwined with the fabric of Boston's surroundings. Molasses flowed into Boston, transformed into rum, and then dispersed to local and distant taverns. Simultaneously, commodities such as cod, lumber, and livestock embarked on their journey to the West Indies. The repercussions were significant: livelihoods were lost, coupled with the agonizing physical symptoms of rum withdrawal. This combination inevitably led to a populace willing to resort to almost anything to satisfy their craving and resurrect the rum trade.

Perhaps the narrative of the temperance movement and prohibition has skewed our perception of history, favoring a perspective akin to tea drinkers. Alternatively, it's plausible that we haven't dedicated enough time to excavate the profound context of those who lived in the past. Regardless, my aspiration is to use this episode to shed light on the often-overlooked history of the 1700s. By immersing the reader in the shoes of tavern owners and their patrons, I aim to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the era – an understanding that goes beyond facts and figures and delves into the visceral experiences of the people who shaped history.

Andover's intriguing connection to rum

Back in the 1640s, Andover began to flourish with its earliest settlers, and within the following six decades, it burgeoned into a community of over 500 people. This thriving population established itself as a notable hub for both local and international trade, with a distinct focus on industries like sawmills, ironworks, and lumber. The exchange of lumber to the West Indies brought back coveted treasures – sugar, molasses, and, of course, rum. Amidst this prosperity, Andover also faced challenges, grappling with Indian attacks, a smallpox outbreak, and the infamous Salem Witch hysteria.

During the 17th Century, six taverns graced Andover, each coming and going, yet only Parker's, Chandler's Horseshoe, and Osgood's endured into the 18th century. The preferred drink of choice shifted to rum, accompanied by an array of new concoctions designed to enhance its palatability. The historical records from this period indicate a surge in "undesirable behavior," leading to multiple petitions against the Horseshoe tavern, the occurrence of the community's first murder, and the implementation of a curfew to "manage" the escalating issue of rowdy and inebriated conduct. Notably, these records mirror the rising availability of rum.

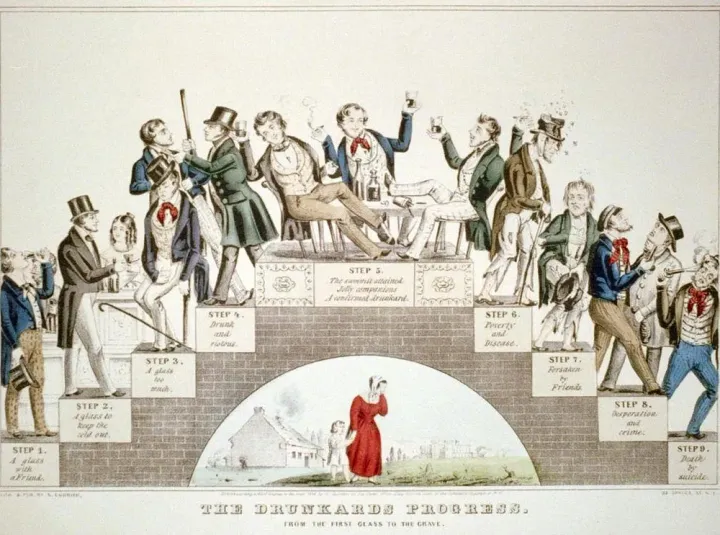

As the 18th century dawned, colonists found themselves consuming up to seven drinks a day, with Cider, Beer, and now rum gaining traction in ever-increasing quantities. Between 1690 and 1790, a beverage known as Flip, a blend of rum and beer, took center stage as "the drink" of preference. Alarming patterns emerged, marking the onset of an alcohol epidemic, with a growing number of citizens now grappling with alcoholism.

And so, Andover's story intertwines with the history of rum, weaving a tapestry that reveals the complex interplay between trade, society, and human behaviors. But Andover is not in isolation.

Is Rum the True Underlying Cause?

Before we delve into the specific taverns of Andover, let's set the stage by discussing the broader context of Massachusetts in the 1700s. Andover's taverns, much like those in neighboring towns around Boston, were buzzing with the latest news and happenings of the time. Stepping into the shoes of these citizens allows us to gain a deeper understanding of that era.

Rum, an alcoholic beverage, finds its origin in the industrial byproduct of sugar production – molasses. As sugar crystallized in clay pots, a thick, dark syrup trickled out from the pot's base. About one pound of molasses was yielded for every two to three pounds of sugar. This molasses was repurposed as livestock feed, fertilizer, and disposed of in various ways, including being dumped into the ocean. The more sugar that was produced, the greater the surplus of waste. This dilemma led to the discovery that molasses could be distilled to create rum.

In his seminal work "The Wealth of Nations" (1776), Adam Smith noted that sugar planters relied on the profits from rum and molasses to cover the expenses of their cultivation. The substantial revenue generated from sugar sales was nearly all profit. (And a bottle of rum) Many sugar producers saw the profits from rum as a means to offset costs, leading to investments in improved distillation techniques and higher quality rum production.

The trade of rum to cities like Boston and Newport was a significant enterprise. Goods like livestock, lumber, and other commodities, including lumber from Andover's Simon Bradstreet, were sent south to Barbados, where the exchange of "Good Rume and Mallasces" was highly lucrative. Over 90% of rum from Barbados and Antigua, and 100% from other islands, found its way to mainland North America. Between 1726 and 1730 alone, over 1 million gallons of rum were shipped to the northern colonies. However, much of the rum arriving in Boston or Newport had brief stays, often continuing its journey to destinations like Newfoundland or Virginia, where it facilitated trade for cod or tobacco.

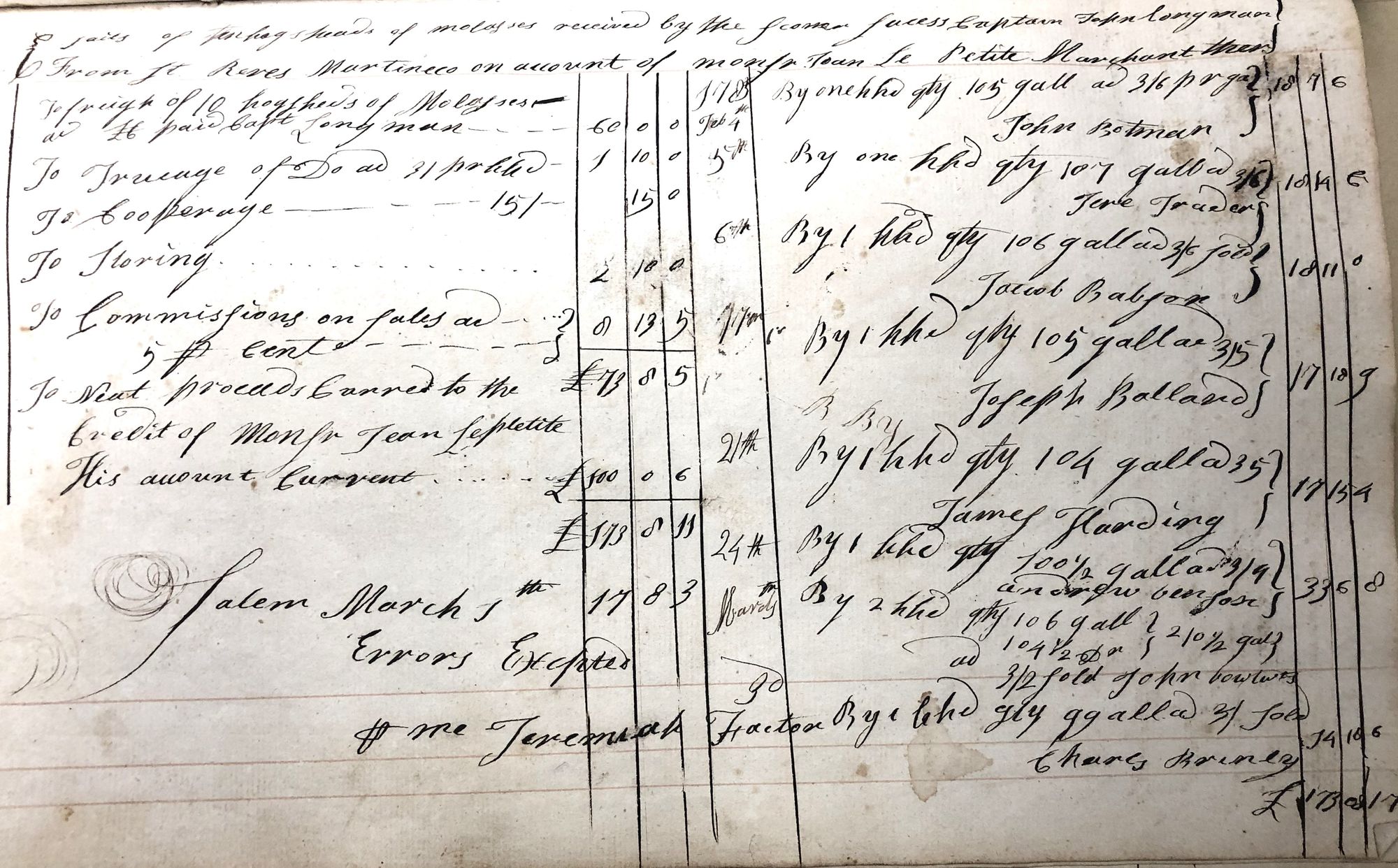

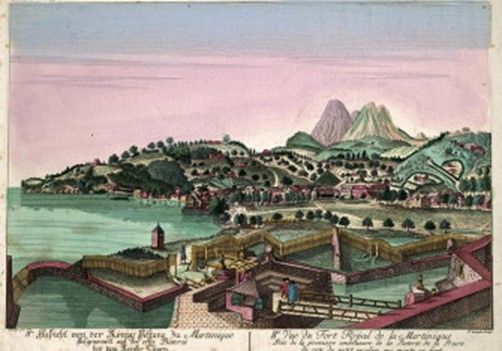

The West Indies trade involved various distillers from British, Spanish, French, and Dutch islands. Interestingly, French molasses was preferred, despite Barbados being a British colony. The reason was its affordability – molasses from French islands, such as Guadeloupe, Grenada, and Martinique, was nearly free due to limited local demand and protective measures for the French wine industry. This prompted Boston's trade with French islands to expand, particularly with Martinique, as production increased, and prices dropped.

By 1716, North America's rum industry was flourishing, leading to a decrease in imports from British islands, particularly Barbados and Antigua. This shift caught the attention of these British colonies, resulting in complaints to Parliament. Parliament's response was the Molasses Act of 1733. This act allowed "favorable" trade, permitting lumber, grain, and horses to be sent to non-British islands, while imposing substantial tariffs on sugar and molasses.

With half a million colonists paying higher prices to benefit just 50,000 residents of British islands, North American merchants and traders were incensed. They faced a choice: comply with the Molasses Act or defy it. Trade persisted as before, disregarding the duties and contributing to the growth of New England's rum distilleries. Ships from New England started routing through free Dutch or Spanish ports before reaching French islands to avoid potential seizure or tariffs. Astonishingly, the duties on French molasses even decreased after the Molasses Act. Over the three decades before the act, the Crown collected £13,702, which plummeted to a mere £2 by 1735.

This complex historical narrative uncovers the intricate relationship between rum, trade, legislation, and the strategies employed by various stakeholders in the colonial era.

New England Rum

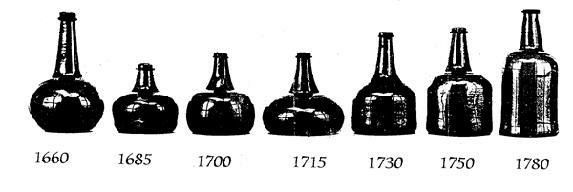

Back in 1684, the first distillery in North America began operating in Providence, RI. However, it wasn't until around 1700 that the rum trade in North America truly came into its own. A combination of factors contributed to this development: immigrant distillers settling in the colonies, the increased availability of molasses, the expansion of a robust trading fleet, and the growth of the slave trade to provide much-needed labor. This environment led to rapid growth in the number of distilleries.

Let's focus on Boston: in 1688, they imported about 156,000 gallons of molasses (half of which would become rum). Fast forward to 1717, and Boston was producing a whopping 200,000 gallons of rum annually. By 1750, the city boasted over 25 distilleries, and beyond Boston's borders, another 10 distilleries were scattered across places like Watertown, Haverhill, Salem, Charlestown, and Medford.

Interestingly, despite the proliferation of these distilleries, the focus was often on procuring inexpensive molasses and selling the resultant rum at similarly affordable prices. "New England Rum" earned a reputation for being of lower quality compared to the esteemed West Indian rum. Maybe this is how New Englanders earned their reputation for thriftiness? However, there was one exception – the town of Medford. Sometime between 1715 and 1720, Medford ventured into the scene and began producing a notably high-quality product. By the time Paul Revere made his famous midnight ride, even he couldn't resist a detour, stopping at the Medford Tavern. Legend has it that Revere took a moment to share a drink with Captain Hall, an opportunity he deemed more important than the pressing matters of his mission. It seems that when it came down to it, nothing could beat a good glass of rum!

This glimpse into the world of New England Rum reveals a fascinating interplay between economics, trade, reputation, and taste. As the industry surged, Boston became both a competitor and buyer of West Indies products. Dependent on the supply of molasses, Boston would do almost anything to maintain its livelihood.

Influence of the French and Indian War

The pages of history reveal the profound impact of the French and Indian War (1756 – 1763) on the rum trade. As English and French forces clashed, the repercussions rippled through the trade networks. The British's conquest of the islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe, initially transferring control to the British, was seen as a positive turn for North American traders. This shift allowed them to legally engage with their long-standing suppliers and bypass the onerous tariffs. However, as the war's dust settled, these islands were handed back to France, reintroducing those tariffs. (It's a good guess that the sugar magnates voiced their objections, possibly not welcoming the competition of more affordable rum.)

But the aftermath of the French and Indian War delivered less promising news. It ushered in the replacement of the Molasses Act with the Sugar Act of 1764. The war had drained resources, and Parliament sought financial recovery. Additionally, the British suspected that smuggling had assisted the French, so the colonists were deemed liable to pay. The Sugar Act came with rigorous enforcement, targeting smugglers and prosecuting offenders. Even John Hancock, the bigger-than-life figure known for importing French molasses and considered one of the wealthiest men in the Americas, saw his sloop, Liberty, seized under charges of smuggling. Although these charges were eventually dropped, Hancock began witnessing the Sugar Act's impact on his fortunes. Over time, this would influence his political allegiance toward supporting the Revolutionary cause.

Disapproval of the Sugar Act reverberated across the northern colonies. In Massachusetts, boasting over 38 distilleries, and with just a mere 3% of imported molasses originating from British islands, citizens were incensed. Some distillers closed shops, while others either absorbed the increased expenses from tariffs or turned to smuggling. Smuggling persisted and pirates found their numbers swelling.

The assemblies of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania directly voiced their grievances about the Sugar Act to Parliament. Their argument revolved around the notion that without affordable molasses, the colonies' income would dwindle, leading to reduced purchases of British goods. Worse still, the northern colonies might initiate their own manufacturing endeavors, potentially crippling British manufacturers' growth prospects. Even Parliament had to acknowledge the economic impact of molasses and rum on the Colonies. In response, in 1766, Parliament modified the Sugar Act to set tariffs so low that smuggling would become pricier than compliance. This revealed that united colonial efforts had an impact, an invaluable lesson that would play a role in the lead-up to the Revolutionary period.

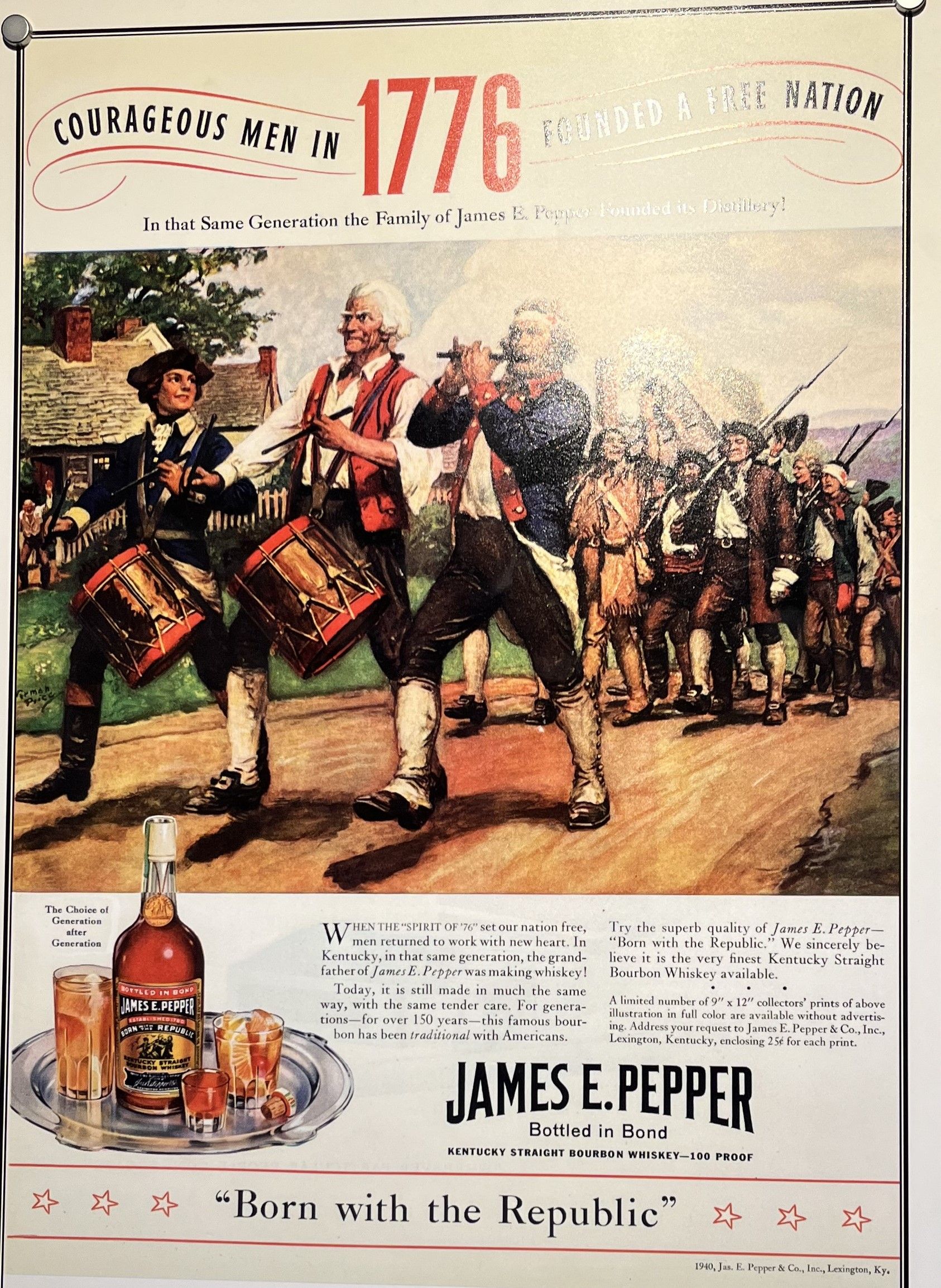

Yet, Parliament's concerns about repealing the Sugar Act and the colonies growing more audacious led to the passage of the Stamp Act. This new law took a heavy toll on New England colonies – a heartland of rum production. The Act served to fund the East India Company, which had suffered due to smuggling and held deep ties to Parliament. The Stamp Act's enforcement triggered a chain reaction: a boycott of British goods, the Boston Tea Party, and, by 1775, the pivotal Battle of Lexington, echoing with the "shot heard round the world." Nevertheless, once again, it was the far-reaching impact of rum and the rum trade that spurred Parliament into action.

While I won't dive into the Revolutionary War here, my aim is to illuminate the influence of rum and the rum trade on the war's genesis. After the war, by 1794, the number of distilleries had dwindled to a mere handful, many operating well below capacity. By 1800, American distilleries produced only 45% of their 1790 output. Rum gradually faded into the past, making way for whiskey as the spirit of the future. Post-Revolution, the allure of fertile lands along the Ohio River Valley catalyzed migration and whiskey production. The economics of cheaper whiskey over rum took root, ushering in the whiskey boom while marking the continued decline of rum's popularity.

In our forthcoming episodes, we'll shift from the panoramic view of the century to a more local and personal perspective. We'll delve into the realm of taverns, exploring what they were like, how they were used, who frequented them, and most importantly, how Andover's taverns played a role in shaping the Revolutionary War narrative.

Sources

Cheever, Susan, Drinking in America, Our Secret History, Twelve, New York, 2015.

Covert, Adrian, Taverns of the American Revolution, Adrian Covert, San Rafael, California, 2016.

Curtis, Wayne, And a Bottle of Rum: A History of the New World in Ten Cocktails, Broadway Books, New York, 2006.

Field, Edward, The Colonial Tavern: A Glimpse of New England Town Life in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Preston and Rounds, Providence, RI, 1897.

McCusker, John T., The Rum Trade and the Balance of Payments of the Thirteen Continental Colonies 1650 - 1775, The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 30, No. 1, Cambridge University Press, 1970.

Comments ()