Jenkins Post House

Stage services in the Boston area gained momentum around 1800. Setting off in the early morning, the stage would reach Andover five hours later for a lunch break and a change of horses at Jenkins’ Post House. The 34-mile journey to Andover necessitated stops for rest and horse changes.

Captain Benjamin Jenkins' Post House (circa 1807) was strategically built along the post-road with the stagecoach in mind. Featuring a tap room, an upper room utilized for dancing, and a side porch for a welcoming entrance, the Post House was well-designed. Notably, the Jenkins family erected a spacious barn to tend to the horses and store the required hay.

Captain Benjamin Jenkins constructed the Post-House for his son Benjamin. Situated at the intersection of Salem Street and Jenkins Road, this establishment, known as a "Post-House," served as a place of entertainment for passengers while stagecoaches changed horses. Each stage accommodated nine passengers and a driver, translating to at least 20 tavern patrons daily. Jenkins Road, a straight north-south route stretching from Boston to New Hampshire, running between the house and barn in the above picture.

Benjamin Jenkins Jr. was born on Apr. 4, 1786, and first married Naamah Kendal Carter who died Feb. 10, 1821. Benjamin remarried Elizabeth "Betsey" Berry b. 1783. Benjamin and Betsey had five children. Benjamin died on May 2, 1835. His wife remained in the home and raised her children. Betsey died on June 24, 1853, at age 60. The children were heirs to the property.

Hay-day of Stagecoaches

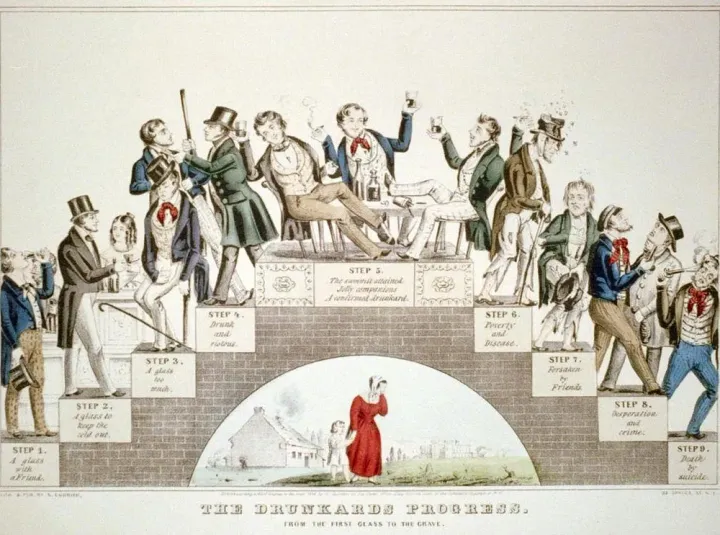

Stages departing from Boston often set out early in the morning to reach the changing center by noon. The post-house ensured that food was readily available for passengers, along with the option to enjoy a drink (cider, flip, beer, or rum) and warm up near the fire—an appreciated comfort. "An hour before the stage coach was due," recounted Frederick Currier in his 1897 history of life in Fitchburg, Mass., "the landlord was to be found in the tap room" preparing his bottles of liquor and "setting his glasses in single file." At the same time, he was urging the kitchen to "make haste with the dinner or the supper, of which there were already premonitory odors of the most appetizing kind." When the stage arrived, the tavern keeper "hastened to the porch and stood there with a smiling face, the picture of welcome as the coach rounded up and the driver threw his reins to the waiting hostlers."

These wayside stops became settings for the exchange of stories and jokes among passengers. I can envision passengers leisurely hanging out on the side porch or gathering around a fire in the parlor during winter. The prominent elm tree in the front provided shade for the house and its visitors, with the wooden protection around it likely serving to shield it from horses as they approached. Nathaniel Hawthorne observed a lively scene in a North Adams tavern, where many dogs were kept in the village, and travelers' canine companions added to the merriment. Dogs freely roamed, entertaining both guests and each other, a charming aspect captured in paintings and historical records.

Dancing was all the rage in the 1800s. The inventory does not highlight a dancing hall, but it is highly likely one room is used for entertainment. When the stage and farming activities slowed down in winter, other pastimes, such as dancing, gained popularity. It served as a social activity that allowed people to mingle without being too forward. Social rules and rule books were published during this time, hovering dance steps, manners, band placement, dress codes (boots were discouraged), and more. A public dance night must have been a sight to behold, with everyone dressed to the nines. It's fascinating how these social gatherings brought people together in the spirit of merriment and camaraderie.

By 1835, the opening of railroads from Boston to Lowell (north), Providence (south), and Worcester (west) rendered the Jenkins Post House obsolete. However, during its "hay-day," this post-house played a crucial role in the area. Even as late as 1955, the property spanned 40 acres, encompassing the house lot, an adjoining orchard, barn lot, and pond lot on both sides of Salem Street, extending up to the road.

After Benjamin's passing on May 2, 1835, his wife Betsey bravely continued to reside in the home, raising their children. The post-house faced challenging times with the advent of early railroads in 1835 and the subsequent collapse of the Eastern Stage Company by 1838. This period undoubtedly presented hardships for the post-house and likely closure.

The barn is the business.

The stagecoaches, each powered by four horses that required regular changes, created a demand for a substantial barn. Judging by the barn's considerable size and numerous windows, it likely had the capacity to accommodate three or more sets of horses, totaling 12 horses, alongside other domestic animals. Given that each horse requires approximately 1-2 acres of pastureland, this implies that around 15 acres were dedicated to horses and other farm animals.

When we take a closer look at the inventory, it becomes clear where most of the estate's value lies. The total worth of the estate is an impressive $1763, with a whopping $1330 attributed to the barn. The inventory sheds light on the diverse array of farm animals, including a horse valued at $50, old oxen at $52, young oxen at $65, 10 cows at $165, one bull at $15, four calves at $10, 4 two-year-old steers at $36, two 3-year-old heifers at $18, 9 sheep and one lamb at $12, five hogs at $53, and 10 pigs at $20. This comprehensive list amounts to a total of $496. (Note: Eastern Stage Company provided their own horses).

The farm equipment, ranging from wagons, carts, ploughs, rakes, hoes, axes, chaise, harness, and more, is valued at $196. Additionally, there's an abundance of grains, including cider, rye, and corn, totaling $288, with an extra $350 earmarked just for the hay. It's fascinating to see how the barn, with its assortment of animals, equipment, and provisions, played a pivotal role in shaping the overall value of the estate. The dedication and hard work invested in the farm truly shine through in these details.

Unfortunately, the barn met its end in a fire in 1922, and the intense heat caused some charring on the adjacent house. Following the fire, old wagons were left to rot in place, and eventually, the lot was sold as a house lot.

Cider Production

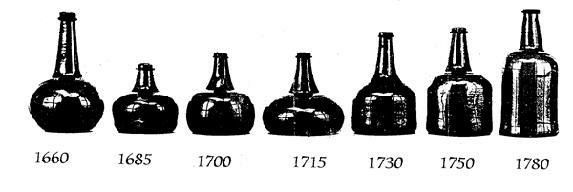

When it comes to drinks in the inventory only cider barrels is mentioned. The early 1800's is the beginning of the temperance movement, so maybe the Jenkins did not approve of drinking? We do know Captain Benjamin Jenkins sent apples to the cider mill at Henry Gray Farm on Salem Street, just a mile away. Henry Gray, who not only had a sawmill on the Skug River but also an apple mill for cider-making, was the go-to destination every fall for the Jenkins family. They would gather their apples and make the short trip to Gray’s mill to crush them into fresh cider.

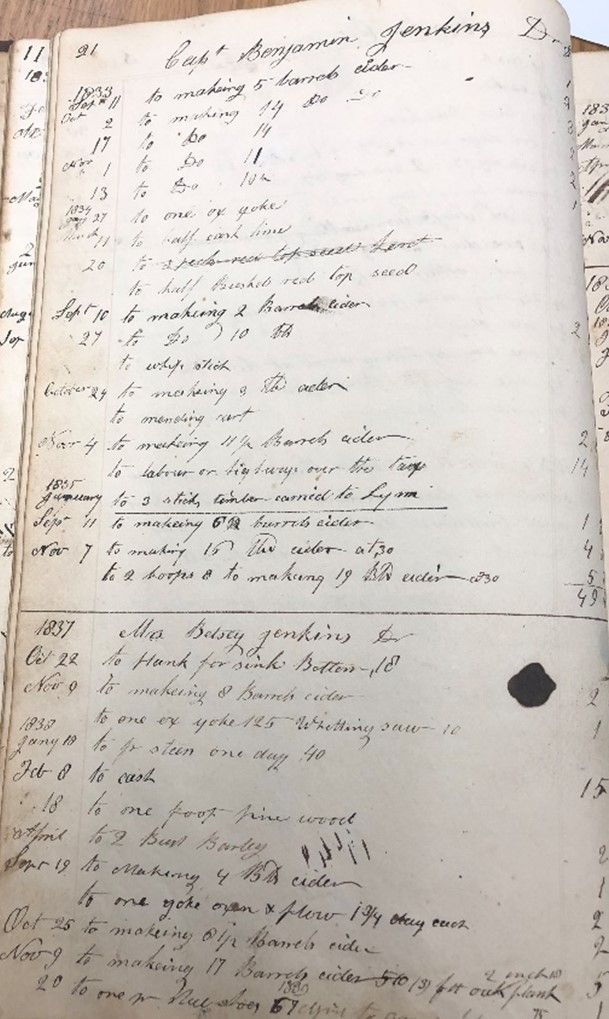

According to Gray's logbooks from September 11 to November 13, 1833, Captain Benjamin Jenkins had a whopping 54 barrels of cider produced in 5 batches, totaling approximately 1890 gallons. To put that into perspective, a typical family would consume about 10 barrels annually, leaving the remaining 44 barrels for the enjoyment of tavern guests. The Jenkins, much like many farmers in the 18th and 19th centuries, had dedicated land for apple orchards. With a yield of 54 barrels of cider, we can estimate that Jenkins had at least 3 acres devoted to apple production. Those apples weren't just for cider; they were also used for making dried fruit, preserving, and baking fresh pies.

After Captain Benjamin Jenkins' passing in 1835, his wife Betsey continued the tradition of sending apples to Gray Farm. However, by 1837, the volume had decreased to only 8 barrels, just enough for family consumption. It's reasonable to assume that with her husband's passing, and with five children under the age of 13, she makes some hard choices. With the advent of rail traffic, and the collapse of the Eastern Stage Company in 1838, Betsey likely decided to discontinue the Post House operation.

Sources

Andover Center for History and Culture, write-ups and photos of Jenkins Post House, https://www.andoverhistorical.org/.

Andover Historic Preservation Site, write-ups and photos of Abbot Tavern, Welcome to the Andover Historic Preservation Web Site | Andover Historic Preservation (mhl.org).

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Fitch, Caroline, Travel Diary, 1836. Old Sturbridge Village Research Library. Edited by Old Sturbridge Village.

Larkin, Jack, Dining Out in the 1830's, Published by Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge MA, 1999.

Comments ()