17th Century Drunks

Is everyone drunk in the 17th century?

In 1658, Mr. Sergeant John Steven found himself facing charges of intoxication and was summoned to court. His servant, Lovejoy, testified against him, stating that he had observed Mr. Steven “reele [really] coming to me”. Lovejoy further explained that Stevens was so intoxicated that he couldn't walk or stand properly and appeared as if he were a child just learning to walk. Lovejoy described the strong liquor Steven had consumed “may well be called KILL DEVIL [rum] for he thought it would kill devil and man too”. The story didn't end there for Mr. Stevens. By the end of that year, the men of Andover had petitioned to change his title from Sergeant to John Osgood.

During the 17th C, consumption of kill-devil increases, and many become addicts. Benjamin Franklin highlights the issue in the early 18th C by making light of the growing issue under his alias, Mrs. Silence Dogood writes,

"They are seldom known to be drunk, they are very often boozy, cogey, tipsy, foxed, merry, mellow, fuddled, groatable, confoundedly cut, see two moons; are among the Philistines, in a very good humor, see the sun, or the sun has shone upon them; they clip the King’s English, are almost froze, feverish, in their altitudes, pretty well entered, etc. In short, every day produced some new word or phrase which might be added to the vocabulary of the tipplers."

Inside a 17th C Tavern

During the 17th century, inventories providing insight into the furnishings of taverns were quite scarce. However, the Essex Institute in Salem, Massachusetts, possesses a valuable record in the form of William Clarke's Probate inventory dated April 25, 1647, which sheds light on the items found in his house and tavern.

In Clarke's tavern, various provisions were stocked, including 3 bushels of Indian corn, 15 bushels of wheat, and 35 bushels of malt. Within the kitchen area, there were 4 ale quarts, 1 pint, 6 beer cups, and 4 wine cups. Down in the cellar, hogsheads were stored for containing liquids (likely beer) or other goods.

Despite the busy nature of Clarke's tavern, its capacity was somewhat constrained by the limited number of visitors who could be served drinks simultaneously, as the total number of containers added up to only 15. Of course, this assumes that there was no sharing of a single container, which was quite common.

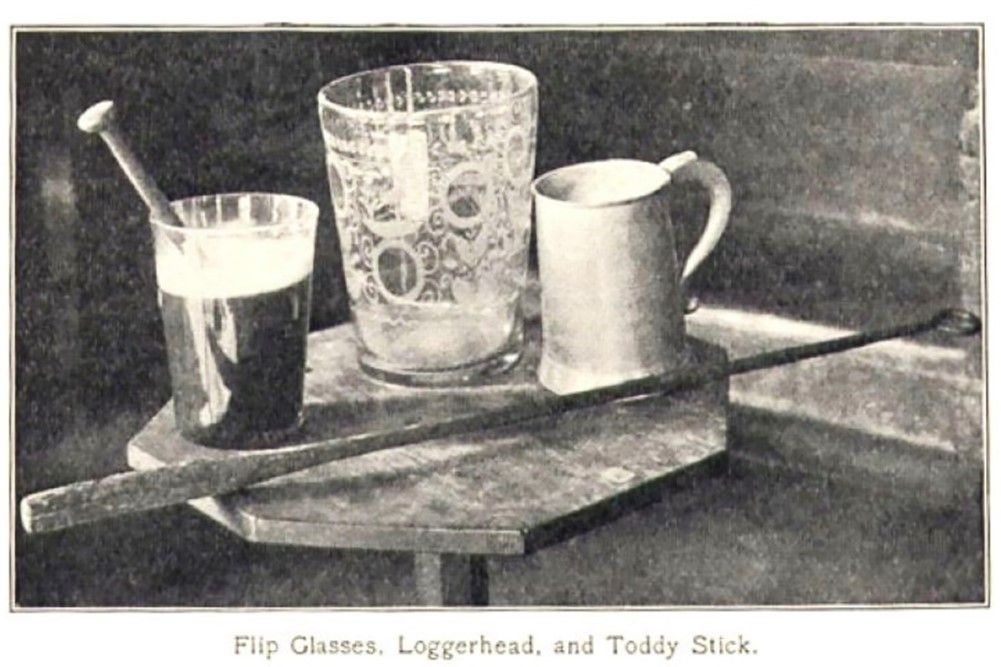

The furniture is simple and unpretentious. Stools, benches, and/or a few "tavern tables" offer seating options to the guests. Although no mention of fireplace tools needed to heat up a drink, they likely had a loggerhead. A loggerhead is heated up in the fire coals and used to prepare hot drinks, especially flips, which are desired for their frothy and slightly burnt taste. The loggerhead, it is a long poker with a round circle head. Also referred to as a flip-dog or hottle, this tool is instrumental in heating drinks and creating frothy textures by dipping it into the beverages.

Taverns are gathering spots

Taverns were informal clubs and gathering spots where men would meet. They frequently hosted civic meetings, militia drills, and various committees. One of the busiest days at any tavern was Training Day, as required by the Court since 1637. Each town had to hold militia training days eight times per year, and men between 16 and 60 were expected to participate. Each man came with a “musket, a pair of bandoliers (to hold up a heavy gun & equipment), powder, pouch, bullets, sword, belt, worm, scourer, rest and knapsack” to practice the skills necessary to live among the Indians. In 1664, Andover has 24 taxpayers, so Training Day had an estimated 30 men. After the exercises, the men would relax with a beverage and catch up on news, either through a town meeting or friendly conversations, making Training Days an all-day affair and a profitable day for the tavern owner.

John Osgood, who later became Captain, was listed as the Andover militia's second sergeant around 1658/59 after taking the job following the drunken behavior of the first sergeant, Mr. Steven. As the militia leader typically chose the Training Day location, it is likely that the militia trained at Osgood's tavern. Although Osgood wasn't officially licensed until 1687, he likely served and sold beer and/or rum without a license, a common practice at the time. I can only imagine how good an aim the militia had after a few drinks!

During the 17th century, taverns served a role like today's newspapers. The local taverns would post notices of town meetings, elections, new laws, sales, auctions, and records of property transfers. The innkeeper, much like a present-day bartender, was often well-informed about local news and events. Other activities which took place among the patrons at taverns included the borrowing and lending of money and game playing (dice, cards, billiards, etc.).

Taverns often had stocks and whipping posts nearby, allowing citizens to witness justice being served firsthand. Auctions, including those of items and people – such as criminals and paupers – were also common at taverns. Although it's unclear if auctions took place in Andover, several affluent residents owned slaves, both white and black. Simon Bradstreet, for instance, owned a "man," though the number and extent of slaves in the area were not well-documented. Regrettably, over the next two centuries, Andover residents continued to own slaves, with the last one being freed in 1840.

The history of these taverns and their role in the community provide us with valuable insights into the past and how societal norms have evolved over time.

Dancing was such a beloved activity that even the Puritans couldn't completely banish it, although they considered it a temptation towards sin. Nevertheless, dancing remained a popular and enjoyable form of entertainment. In many taverns, weather permitting, dances were held outdoors. As time went on, special rooms were set aside solely for dancing parties.

Where there's dancing, there's music! Music and singing were incredibly common in the 17th century. Both men and women delighted in music and song. Puritans, in particular, loved singing songs of praise but strongly disapproved of "bawdy ballads" and other profane tunes often associated with drinking songs. Taverns played a significant role in fostering song and music, as evidenced by the Sun tavern in Boston advertising a "concert of music" in 1735. A few common songs trace their roots to at least the 1700's, including: Although somewhat altered in content and meaning, well-known surviving songs include "Three Blind Mice," "Pop Goes the Weasel," "The Bear Went over the Mountain," and "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star."

During mid-day breaks from the meetinghouse, people would gather at the tavern, which, by law, had to be located a short distance from the meetinghouse. This provided an opportunity for a warm meal and drink, and during the summer, a chance to relax in a shaded courtyard. Ministers would sometimes lament that parishioners chose the tavern over church and behaved inappropriately. John Adams, in the early 1700s, even wrote in his diary about his unsuccessful campaign against taverns while traveling for his law practice, “Few things have deviated so far from the first design of their institution, are so fruitful of destructive evils, or so needful of a speedy regulation, as licensed houses,” he complained. Later Adams realized that taverns have people of influence. “You will find the [tavern] full of people, drinking drams, phlip [flip], toddy,” Adams wrote, “if the ancients drank wine as our people drink rum and cider, it is no wonder we hear of so many possessed with devils”, wrote John Adams.

Overall, taverns served as vital social hubs where people indulged in dance, music, and camaraderie, making them an essential part of life in the 17th century.

Taverner owners look to increase consumption and profits

Drinking was encouraged, for example Benjamin Franklin under alias of Mrs. Silence Dogood writes,

“Tis true, drinking does not improve our faculties, but it enables us to use them; and therefore I conclude that much study and experience, and a little liquor, are of absolute necessity for some tempers, in order to make them accomplished orators.

The more people enjoyed their drinks, the more profit it meant for the tavern owner and their family. Take Thomas Clark, for instance, who sold beer to his customer Samuel Bennett an impressive nineteen times between June 1657 and September 1658. Every time Bennett visited, he happily drank 3 quarts of beer, which Clark sold at the regulated price of 2d. per quart. Over the course of a year, Bennett drank an average of 84d. worth of beer. If we consider that Bennett was just one of 40 customers, Clark's Ordinary could expect to sell approximately 3,360d. or £14 worth of beer in a year. This additional income was quite significant, especially when compared to the earnings of a field hand in 1659, who made about £2 6s. per month.

Having a tavern meant the ordinary keeper enjoyed more income compared to a home brewer. Of course, having a wife who could brew excellent beer was a bonus, ensuring even more satisfied customers.

Consumption to drunks

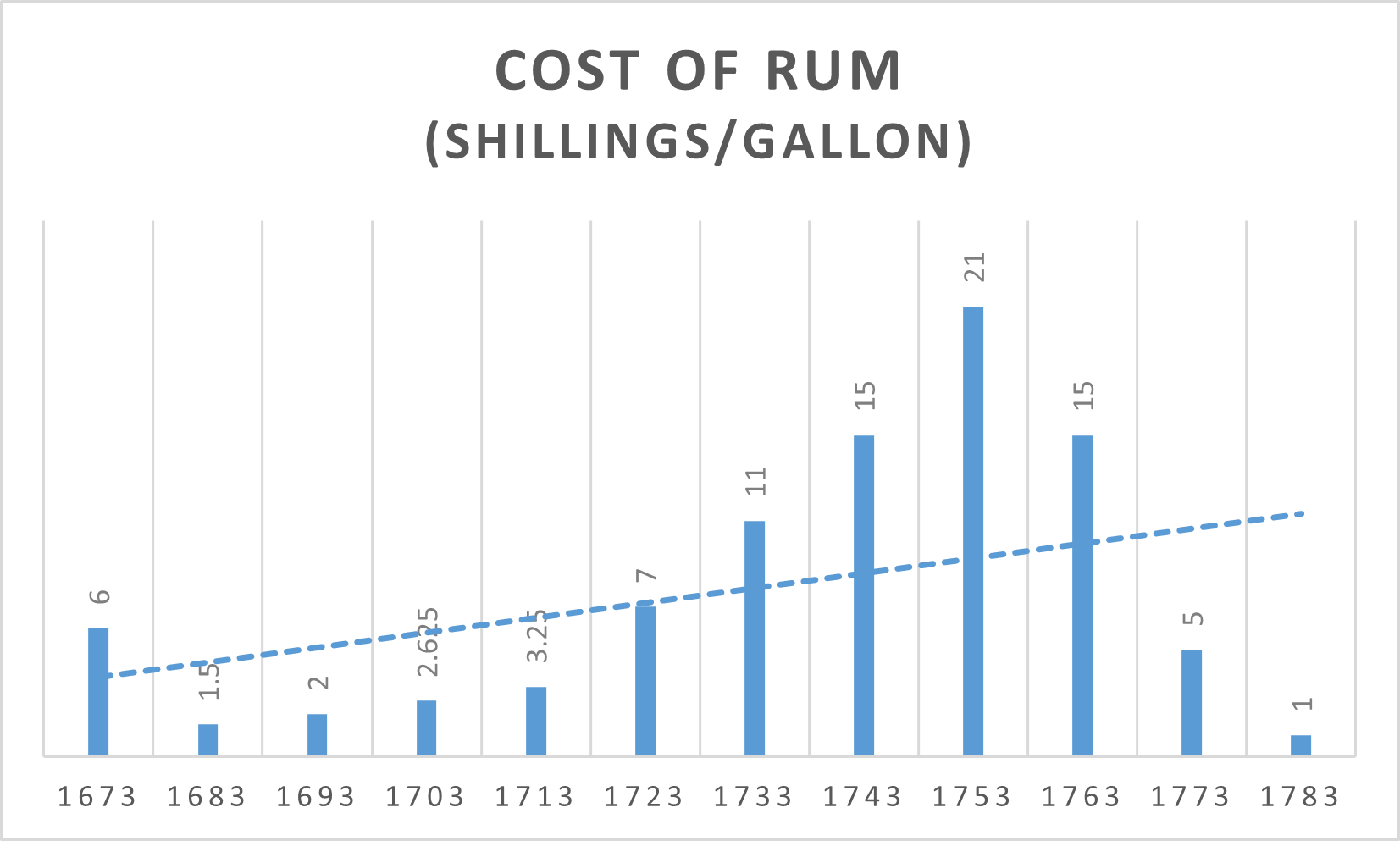

In the mid-1600s, taverns primarily served cider, beer, and wine. Early rum was expensive, priced at 6s/gal, and the taste wasn't as appealing as the nickname "Kill-devil" might suggest. However, as time passed, the cost of rum decreased, and its quality improved significantly.

Rum became a staple drink, surpassing all others by the late 1600s and early 1700s. While home farmers produced cider, taverns were the go-to places for serving rum and rum-related mixed drinks, which became exceedingly popular. The historical price data for rum further emphasizes its growing significance over the years. From the chart below we see the steadily increasing price of rum through the mid-18th C. Rum was here to stay.

Only during the embargo of Boston before the outbreak of War do we see prices fall. Following the Revolutionary War, approximately 30 distilleries in the Boston area disappeared. Tea was not the only thing colonists gave up drinking during the War.

Just like today, taverns offered a variety of specialty drinks to attract more patrons, more consumption, and create a lively atmosphere. In Salem, the best beer was available at an affordable price of 1-1/2 d. per quart. Meanwhile, if you were in Canton, you wouldn't want to miss the famous flip, a delightful mixed drink comprising rum, beer, and frothy egg whites, expertly served at May's tavern. And for those seeking a touch of warmth and sweetness, the Westborough tavern was known for its delectable, mulled wine.

As the Revolutionary War approached, drinking habits among colonists were quite remarkable. Those aged 15 and above consumed an average of 3.7 gallons of spirits annually, equivalent to about 5-7 shots per day! By 1790, this figure had surged to 5 gallons of spirits, in addition to 34 gallons of beer and 1 gallon of wine per person. The love for spirits, beer, and wine was undoubtedly an integral part of the colonial lifestyle.

In future episodes, we'll delve into how alcohol impacted the city of Boston and its role in the beginnings of the Revolutionary War. For now, let's enjoy the fascinating stories and traditions surrounding these historic taverns and their captivating drinks!

Sources:

Abbot, Elinor, Our Company Increase Apace, History, Language, and Social Identity in Early Colonial Andover, Massachusetts, SIL International, Dallas, TX, 2007.

Baily, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston 1880.

Cheever, Susan, Drinking in America, Our Secret History, Twelve, New York, New York, 2015.

Curtis, Wayne, And a Bottle of Rum, a History of the New World in Ten Cocktails, Broadway Books, New York, New York, 2006.

Earle, Alice Morse, Stage-coach and Tavern Days, The MacMillan Company, London, 1900.

Field, Edward, The Colonial Tavern: A glimpse of New England Town Life in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Preston and Rounds, 1896.

Hirsch, Corin, Forgotten Drinks of Colonial New England, American Palate, a Division of the History Press, Charleston, SC, 2014.

Larkin, Jack, The New England County Tavern, Old Sturbridge Village Publications, Sturbridge, MA, 2000.

Wright, Louis B, The Cultural Life of the American Colonies, Harper Books, New York, New York, 1957.

Salem Quarterly Courts Files, vol.1, leaf 81.

Comments ()