Archaeology of Lucy Foster’s Homestead

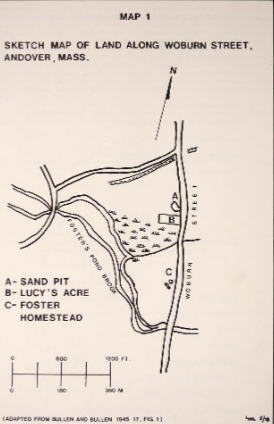

Lucy Foster’s Homestead underwent a significant archaeological exploration in 1945. Adelaide and Ripley Bullen, along with their team, unearthed intriguing findings, including the remains of a 12’ x 12’ house foundation with a cellar 55” deep, a vegetable cellar (an oval pit, 84” x 100” x 43” deep), a well (3’ dia. and 70” deep), and a dump (10’ x 20’ x 6“deep) on a one-acre lot. Although items were scattered across the site, the dump area proved to be particularly concentrated.

The question arose – was this site involved in the tavern business? Examining the site as a whole, exploring individual pieces, and analyzing the materials found became essential in answering this intriguing query.

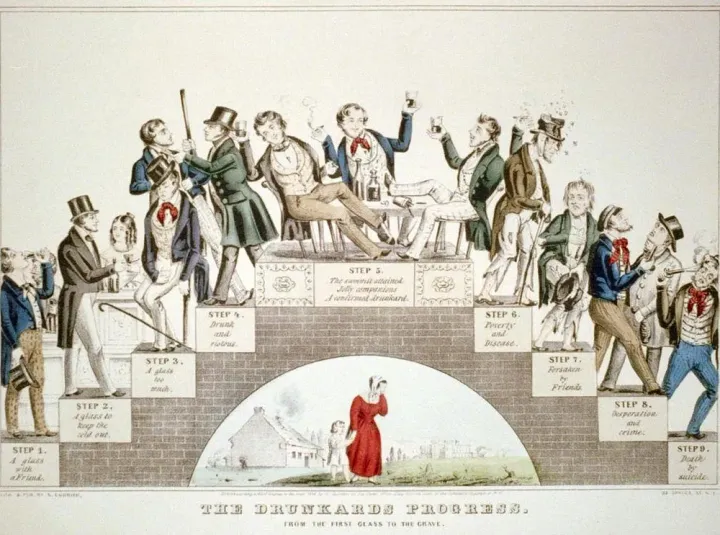

Considering its location, Lucy Foster’s homestead could indeed have been a favorable spot for a tavern. It had previously supported two taverns—the Horseshoe (1690-1715) and the Ballard Tavern (1771-1798)—on this well-traveled road. When Lucy inherited the one-acre property along Woburn Street in 1812, the area likely attracted stagecoaches and other travelers. It would be two more decades before the railroad replaced the stagecoach, and the Essex Turnpike (now Main Street) became the primary route from Andover to Boston. Additionally, the distance to other town taverns, such as the Elm House or the Blunt Tavern, was over three miles, taking more than 30 minutes by horse—an inconvenience for those seeking refreshment.

In the 1830s, with the advent of the railroad, all town taverns experienced reduced traffic, leading to their eventual closure. Lucy maintained her homestead until her death in 1845, making it unlikely that it continued as a tavern in later years—at least not a public site. The possibility of it being a venue for invitation-only gatherings remains speculative. Let's discuss the other evidence surrounding Lucy Foster's life and the possibility of being a forgotten tavern.

Site, Facility

The site, occupying just one acre, encompasses a house, garden, vegetable storage, well, privy, and space for livestock. Lucy inherited a cow, but there's no mention of a barn. So, did she perhaps house her cow across the street in the Foster’s barn, or did she opt for chickens or other animals with a shed for shelter? The essentials for survival are present – a garden for vegetables, storage, and the helpful presence of chickens, nature’s pest control.

The house, a mere 144 sq. ft. with attic storage, is compact by today's standards. Contemporary tiny houses can be up to 400 sq. ft. in floor space. Even first-period homes built before 1720 were larger, with 56% being a single-room style averaging 16’ x 14’. While many single-room homes were expanded or demolished over the years, a typical tavern in someone's home around that time was likely about 16’x 14’.

Comparing this, Lucy's house was smaller than the average tavern of that era. It needed to accommodate additional items not commonly seen in a barroom, such as a bed that could fold away. The site could handle a limited number of visitors or host outdoor seasonal events, but it wasn't spacious enough to attract a significant customer base. Could it host 3-4 people plus Lucy? Certainly, but it would be undeniably cozy.

Materials found

The primary reason people wonder about the site's potential as a tavern is the abundance of items found that could have been used while serving beverages or meals. The excavation revealed a diverse array of small items, including buttons, fasteners, glass, earthenware, redware, pipes, nails, hinges, shovel, candleholder, buckles, metal forks and knives, scissors, knife blade, broach, padlock, eyeglasses, and various bones. The animal remains showed that 82% of cattle, sheep, or hog were butchered using a cleaver, suggesting preparations for stews rather than elaborate meals. This wasn't a place for fancy dining experiences.

Further analysis of the over 2000 ceramic shards reveals that they fall into the most common classes of earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain. Earthenware, often referred to as creamware or pearlware, stands out as the most prevalent category. Creamware, as its name implies, features a cream color resulting from an off-white body and a yellow glaze. Its production began around 1762 or earlier, with Josiah Wedgwood likely being the inventor. Creamware was often adorned on the edges and remained in production until 1820.

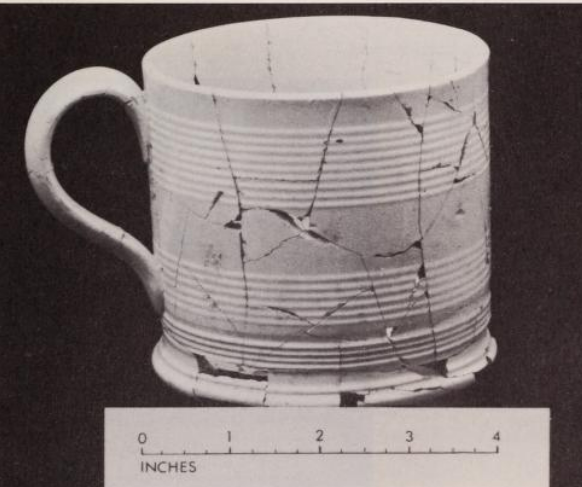

A notable variation of creamware is the underglaze technique known as Annular or Mocha decorating. Annular utilizes various colors, often in geometric patterns, while Mocha is adorned with rich colors like black, green, brown, and yellow, incorporating natural elements such as ferns. This served as an affordable and attractive alternative to creamware or pearlware. Today, antique dealers commonly refer to this popular earthenware as mocha, appreciating its high value for attractive designs and perfect condition. Most mocha was produced from 1780 to 1815, reflecting its popularity during that period.

Pearlware, a variation of earthenware introduced in the 1770s, features a whiter body achieved by adding chert to the paste and a bluish-white tint to the glaze. Once again, Josiah Wedgwood played a pivotal role in developing this more desirable ware around 1780, naming it "pearl white." It served as a substitute for Chinese porcelain and gained popularity among the growing middle classes. Pearlware saw various decorative techniques, including hand painting, transfer prints, and edge-decorating, making it highly sought after. Surprisingly, pearlware outlasted creamware, remaining very popular through 1840.

Redware, with its buff-red clay color, was prevalent during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries in both England and America. Often glazed on one or all sides, redware served utilitarian purposes like pots or mugs.

Local stoneware, produced in eastern Massachusetts during the 18th and 19th centuries, was fired at higher temperatures and typically left unglazed. White salt-glazed stoneware reached its peak around 1760 and was mainly associated with storage on the site.

Porcelain, made from kaolin clay, is recognized for its white body. While Chinese porcelain gained wide popularity in the late 1700s and 1800s, it remained an expensive luxury. Everyday substitutes like pearlware and creamware became favored choices during this period.

2000 Shards

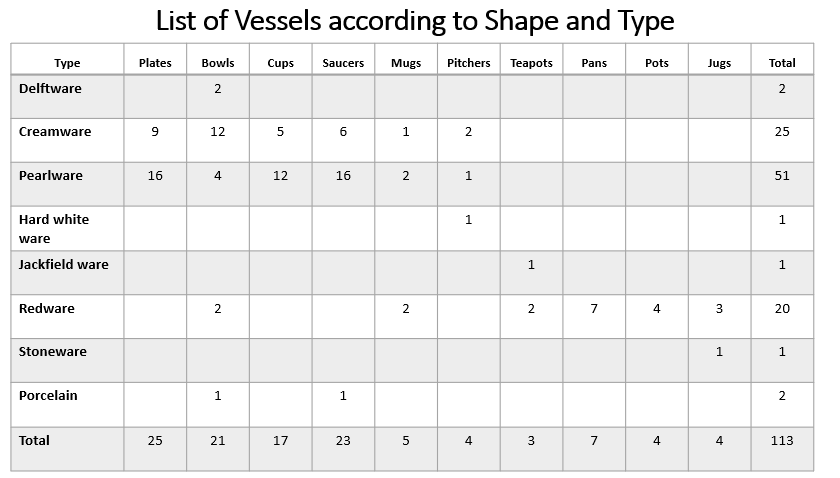

Among the over 2000 shards discovered, the Bullens managed to reconstruct 113 vessels, with two types of glazed earthenware constituting 77% of all shards—specifically pearlware and creamware.

· 63% Pearlware emerged as the predominant material at the site. Lucy possessed a diverse collection of pearlware, featuring transfer prints, hand-painted varieties, molded edges, and edge-painting.

· 17% Redware, likely of American origin, was predominantly used for cooking purposes. These affordable cooking utensils were designed for everyday use.

· 13% Creamware, with much of it being plain or edge-painted, adorned the site. While the fancy decorations of both annular and mocha decorating were common, the creamware on the site displayed simpler designs.

· 2% Chinese porcelain, widely popular but expensive during the 1700s and 1800s, didn't surprise us with its limited presence on the site.

Where is the privy?

The privy would typically be situated away from the well and on the back side of the house, coinciding with the location of the dump. Privies often served a dual purpose, functioning not only as a restroom but also as a disposal area, a pattern observed in many archaeological digs. Interestingly, there's no specific mention of the privy in this case. My hypothesis suggests that the privy was likely in this area, and as was customary, it might have been moved every few years. Over the 32 years that Lucy Foster inhabited this site, the dump area could have accumulated debris from the periodic relocations of the privy. It's essential to bear in mind that the debris found represents what was discarded, not what was preserved, utilized, or had a continued life after Lucy. Additionally, the fragility of items, such as China compared to pottery, influences the composition of the dump.

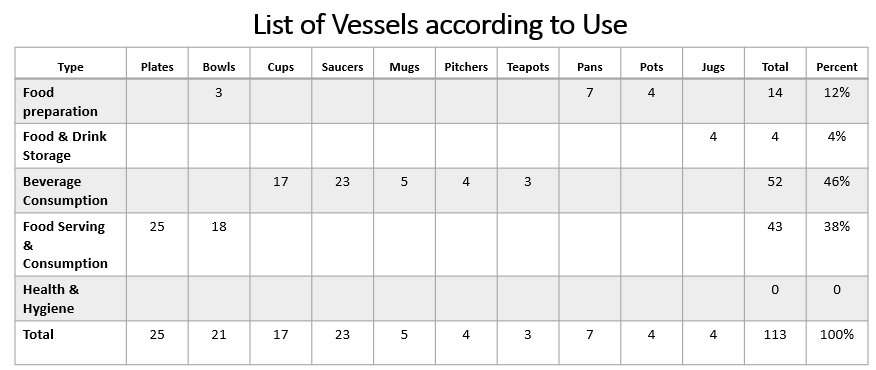

Upon reviewing the reconstruction of the shards, creating a list of 113 vessels reveals a breakdown of items: 25 plates, 21 bowls, 17 cups, 23 saucers, 5 mugs, 4 pitchers, 4 jugs, and 3 teapots. While this breakdown provides valuable information, the focus shifts to understanding the items' actual usage. The POTs Classification aids in categorizing items into five groups based on their functions:

- Food preparation – examples include mixing bowls.

- Food and drink storage - examples include bottles, jugs.

- Beverage consumption and serving – glasses, cups, saucers, mugs, pitchers, punch bowls, punch pots.

- Food serving and consumption – plates, bowls, serving bowls.

- Health and hygiene – chamber pots.

These categories were employed in several tavern sites in Massachusetts, such as the Wellfleet tavern and the Long Tavern (also known as the 3 Crane Tavern) in Charlestown, MA, excavated before 1988 and studied in a dissertation by Christy Cathleen Vogt in 1994. The Charlestown dig stands out for capturing activities within five time periods from 1630 to 1775, represented by five privies of different time periods. Privy #5, covering the years 1744-1770, is the closest in timing with Lucy Foster's site. An intriguing observation from the various privy time frames is that the number of shards related to beverages diminishes, while plates increase. This suggests that over time, taverns evolve into places for both drinks and food, altering the balance between beverage and food-related items.

Examining digs of properties within a specific time and region is crucial for understanding local trends, including drink preferences, eating vs. drinking offerings, and local customs. Privies, used for discarding broken items, serve as rich sources of shards. With limited available datasets, Privy #5 serves as a useful benchmark for period and regional similarities when analyzing Lucy Foster's site. Categorizing shards from Privy #5 at Long Tavern in Charlestown reveals that 27.7% of all shards from that privy relate to beverage consumption and serving (category 3). Upon reclassifying Lucy Foster's site's shards, we find that at least 35 vessels (17 cups, 23 saucers, 5 mugs, 4 pitchers, and 3 teapots) out of 113 are beverage-related, equal to 30.9%. The cups and saucers are tricky. If we add in the 17 cups, the total percentage is over 46%, but cups and saucers are frequently used together, so I am using the saucers only for a more conservative number.

Widely available small bowls called 'sneakers,' designed for individual-sized measures of punch, were often manufactured in England. These bowls, constituting 18% of all findings, could have been used for punch. Punchbowls, straddling the divide between traditional drinks like beer and wine and new hot drinks like tea, coffee, and chocolate, showcase the evolving beverage landscape of the eighteenth century. While it's unlikely that Lucy would be serving chocolate due to her economic status, tea remains a plausible option.

When we include half of the bowls in our totals, the percentage grows to 38.9% related to beverages. Individual punch bowls, sometimes misinterpreted as soup bowls, could explain the inclusion of at least half of the bowls. Some plates are detailed as "soup-plate," given their depth suitable for stew or soup. In conclusion, the Lucy Foster site contains 30.9% to 38.9% of vessels related to beverages, compared to a tavern from the same period showing 27.7%. This strengthens the evidence supporting the idea that Lucy may have offered drinks to the public.

Four pitchers and three teapots stand out among the artifacts. Some of these pots are notably large for brewing tea, especially for an individual living alone. Large teapots were often repurposed for serving hot punch and were referred to as punch pots. The external appearance of punch pots and teapots could be nearly identical, making misclassification common. This hints that Lucy might have utilized these oversized pots for some form of entertainment, as they seem impractically large for a single person.

Conclusion

While Lucy Foster’s Homestead offers a fascinating glimpse into the life of a freed black woman in 19th-century Andover, it doesn't provide conclusive evidence of her lifestyle. We do know that she received support from two sources, coupled with her inheritance. However, being a financially challenged woman living independently for 32 years, Lucy likely needed additional income. The archaeological findings, while not definitive, suggest a notable presence of earthenware associated with hospitality, resembling that of a tavern or restaurant.

What we can affirm about Lucy Foster is her remarkable journey—from a life of slavery to becoming a homeowner not far from her lifelong residence. She embraced motherhood and experienced the generosity of being treated like a daughter when she inherited funds from Hannah Ford Foster Chandler. A member of the South Parish Church, Lucy received support, both moral and financial, from her neighbors to construct her new home. Although leading a modest life, she passed away with dignity and respect.

Sources

Baker, Vernon, Historical Archaeology at Black Lucy's Garden: Ceramics from the Site of a Nineteenth Century Afro-American, Phillips Academy Andover, The Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology, 1978.

Greene, Lorenzo J., Slave-Holding New England and Its Awakening, The Journal of Negro History, Oct. 1928, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Oct., 1928), pp. 492- 533, 1928.

Harvey, Karen, Barbarity in a Teacup? Punch, Domesticity and Gender in the Eighteenth Century, Journal of Design History, Autumn, 2008, Vol. 21, No. 3, Oxford University Press on behalf of Design History Society, 2008.

Martin, Anthony, Homeplace Is also Workplace: Another Look at Lucy Foster in Andover, Massachusetts, Published online: 18 January 2018 # Society for Historical Archaeology 2018.

Vogt, Christy Cathleen, A Toast to the Tavern: An Archaeological Study of a 17th and 18th Century Tavern in Charlestown, Massachusetts (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625863. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5wnm-6v62

Comments ()