Beakers, Mugs, and Bowls

Indulge in the art of libation at Forgotten Taverns. Discover the best way to drink as we guide you through utensils used to sip each drink. Cheers to unforgettable moments! #ForgottenTaverns

“Cider and punch for lunch; rum and brandy before dinner; punch, Madeira, port, and sherry at dinner; punch and liqueurs with the ladies; and wine, spirit, and punch till bedtime; all in punch bowls big enough for a goose to swim in.” as William Black wrote after visiting Philadelphia 1744.

Beakers, Cans, and Mugs

During the Revolutionary War, colonists older than 15 consumed an astonishing 3.7 gallons of spirits per year, equivalent to roughly 5-7 shots per day. By 1790, this figure had surged to 5 gallons, accompanied by 34 gallons of beer and 1 gallon of wine. With such copious consumption, a variety of drinking vessels were in demand. By the 1750s, pewter, earthenware, glass, and stoneware were the most prevalent options, with beakers, cans, and mugs being particularly popular.

Cans and mugs, along with tankards and bumpers, were commonly used terms for these drinking vessels. A "can" referred to a handle-less metal tumbler, while a "mug" denoted a large, straight-sided cup with a handle, available in materials ranging from wood and glass to silver, tin, pewter, earthenware, or stoneware. Even though their shapes varied, we still use the terms "can" and "mug" for beer containers today.

In 1755, Samuel Johnson defined a tankard as a "large vessel with a cover for strong drink." In early America, tankards were crafted from diverse materials, including wood, leather, glass, or earthenware. Despite their material, they all featured a handle and a lid, signifying a sizable drink container. The phrase "He was tanked up," used to describe someone heavily intoxicated, originated from this era and carries the same meaning today.

"Bumper" and "brimmer" referred to glasses used for toasting, such as when drinking to someone's health. Nowadays, these are termed tavern glasses, but in the 18th century, they were known as bumpers. The term "bumper" derived from the act of knocking a glass on a bar top after a toast. According to Noah Webster in 1806, a bumper was simply a glass "filled with liquor to the brim." Similar terms like "biggin" for small bowls or cups, "bowl" for round containers, and "blackpot" or "blackjack" for varnished leather tankards were also imported from Britain to the colonies.

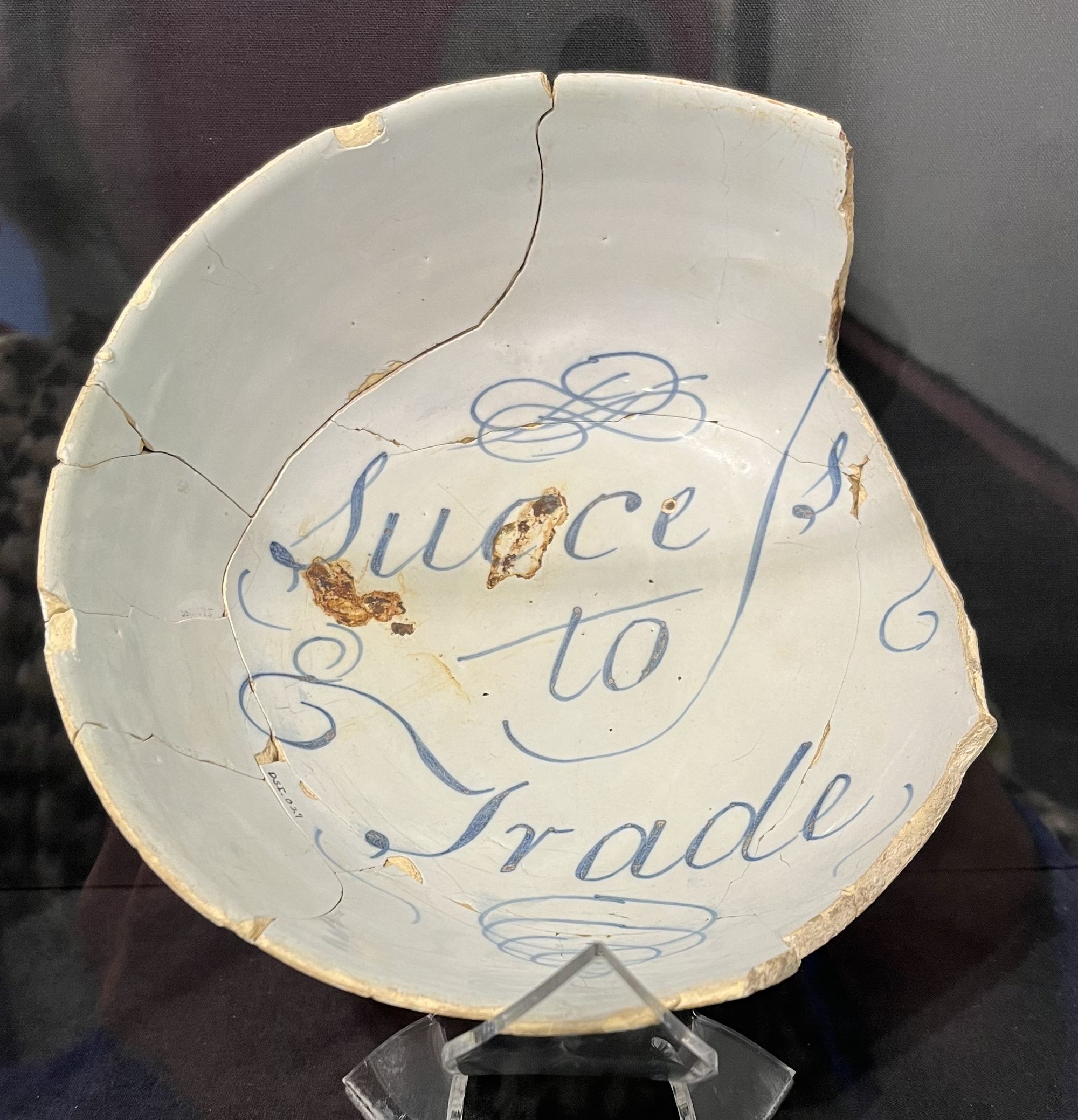

Punch bowls became widespread in the mid-1700s, evolving alongside the increasing popularity of ceramics. These bowls were made from pewter, glass, ceramic, or silver, transitioning from smaller glass tumblers to larger ceramic bowls over time. Taverns, inns, and common taverns all provided punch bowls, often with unique inscriptions serving various purposes, from advertising to fun sayings.

While tea drinking, especially among women, became associated with refined porcelain, punch remained a shared drink often served in communal bowls. Punch pots, resembling large teapots, emerged as a way to balance the refinement of tea drinking with the desire for alcoholic beverages. These pots were a rare solution to the lack of sophistication associated with using punch bowls, bridging the gap between the social norms of the time.

Punch Bowls: A Heartwarming Tale of Porcelain Wonder!

Let's embark on a delightful journey into the captivating world of punch bowls! Our story starts in ancient China, the enchanting birthplace of what we now lovingly call Chinese porcelain or China. During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), porcelain underwent incredible innovations, transforming it into a global sensation. Ming artisans crafted vast quantities of porcelain, enchanting hearts worldwide, especially in Europe.

As we move into the early part of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), China's famed blue and white porcelain stole the spotlight. The Dutch even created their version, making it accessible to all. By the mid-1700s, ceramics had become a household staple, boasting a soft, creamy color, often created at low temperatures to cater to public demands.

In the days before the Revolution, trade with the Far East was under the British East India Company's control. This meant that American colonists could indulge in the pleasures of tea, silk, and porcelain but through English merchants, limiting access to the well-off. Ladies dreamt of fine china for their teapots, yet various ceramics like earthenware and stoneware found their way into homes due to their affordability. (America entered the China Trade following the Revolution. The Empress of China was refitted following many battles in the Revolution and set sail on February 22, 1784.)

In this vibrant era, potters worldwide endeavored to replicate China's porcelain brilliance. Ceramics became the canvas for traditional drinks like beer and wine, served in glass and stoneware, as well as newfound favorites like tea, coffee, and chocolate, elegantly presented in porcelain and fine earthenware. Punch and an array of mixed drinks gained immense popularity, leading to the birth of punch bowls crafted from pewter, glass, ceramic, and even silver. These humble tumblers transformed into larger, exquisite ceramic bowls over time.

By the 1750s, ceramics had become commonplace, and punch bowls followed suit. Traditional drinks of beer and wine met their match in glass, stoneware, and the rougher delftwares, while the rising stars of tea, coffee, and chocolate were elegantly presented in porcelain and fine earthenware. Punch and its delightful companions were served from bowls made of pewter, glass, ceramic, and silver, gradually evolving from tumblers into larger and more splendid ceramic vessels.

Enter Wedgwood! In 1759, this skilled potter revolutionized the ceramic scene by producing high-quality creamware. This cost-effective alternative to porcelain swiftly became a staple in both humble taverns and well-to-do homes. Creamware bowls, along with porcelain counterparts, were cherished vessels for mixing delightful concoctions like punch, flip, and mulled cider.

Picture this: bustling taverns offering beer and ale to the everyday crowd, elegant inns serving wine and spirits in grandeur, and common taverns falling somewhere in between. Punch bowls graced the tables of all these establishments, each bearing unique designs reflecting the spirit of the place. Small bowls in plain pearlware, printed with rum, grog or punch were not only cheap but widely cherished. Larger bowls were advertising, commemorative, or just fun with sayings, like, 'One bowl more and then' or 'Drink fair, don't swear.'

An interesting fact: both men and women relished their drinks from punch bowls, although it was predominantly seen as a man's realm. Women often opted for smaller bowls or sipped tea from delicate cups. Glass beakers also made their debut, adding a touch of elegance to serving punch, especially for the ladies.

The contrast between tea and punch was stark. Tea, often associated with women, was served in exquisite teapots made of the finest ceramic or porcelain. In contrast, punch (and coffee) was considered more of a man's drink, found in taverns or during moments of leisure. Excessive drinking, however, was viewed negatively, highlighting a shift in societal norms.

Now, let's talk about punch pots! Punch pots, though rare and not extensively studied, bridged the refinement of tea drinking with the enjoyment of alcoholic beverages. These ingenious adaptations of tea pots gained popularity in the 1750s. Imagine an oversized teapot designed exclusively for mixing and pouring punch, offering a more refined alternative to the traditional punch bowl.

In the vibrant social tapestry of the time, low-end Taverns welcomed beer enthusiasts, inns exuded grandeur with their wine and spirits offerings, and common taverns struck a balance in between. At each of these establishments, punch bowls took center stage, often boasting unique inscriptions like 'One bowl more and then' or 'Drink fair, don't swear,’ adding a playful touch to the revelry.

Punch was more than just a beverage; it was a shared experience, uniting hearts and sparking laughter. In an era where personal hygiene was a growing concern, the punch bowl stood as a symbol of communal joy. Lively paintings from this time captured the essence of these gatherings, with ladles gracefully transferring punch to individual glasses.

The practice of sharing a punch bowl fascinated foreign travelers, with French and English visitors expressing their intrigue and concerns for hygiene. The punch bowl, though primarily considered a man's domain, welcomed both men and women, creating a vibrant atmosphere of camaraderie and celebration.

So there you have it, a heartwarming adventure into the enchanting world of drinking vessels and punch bowls and the joy they brought to generations! Here's to shared moments, historical traditions, and the boundless creativity of artisans who crafted these treasures!

Sources

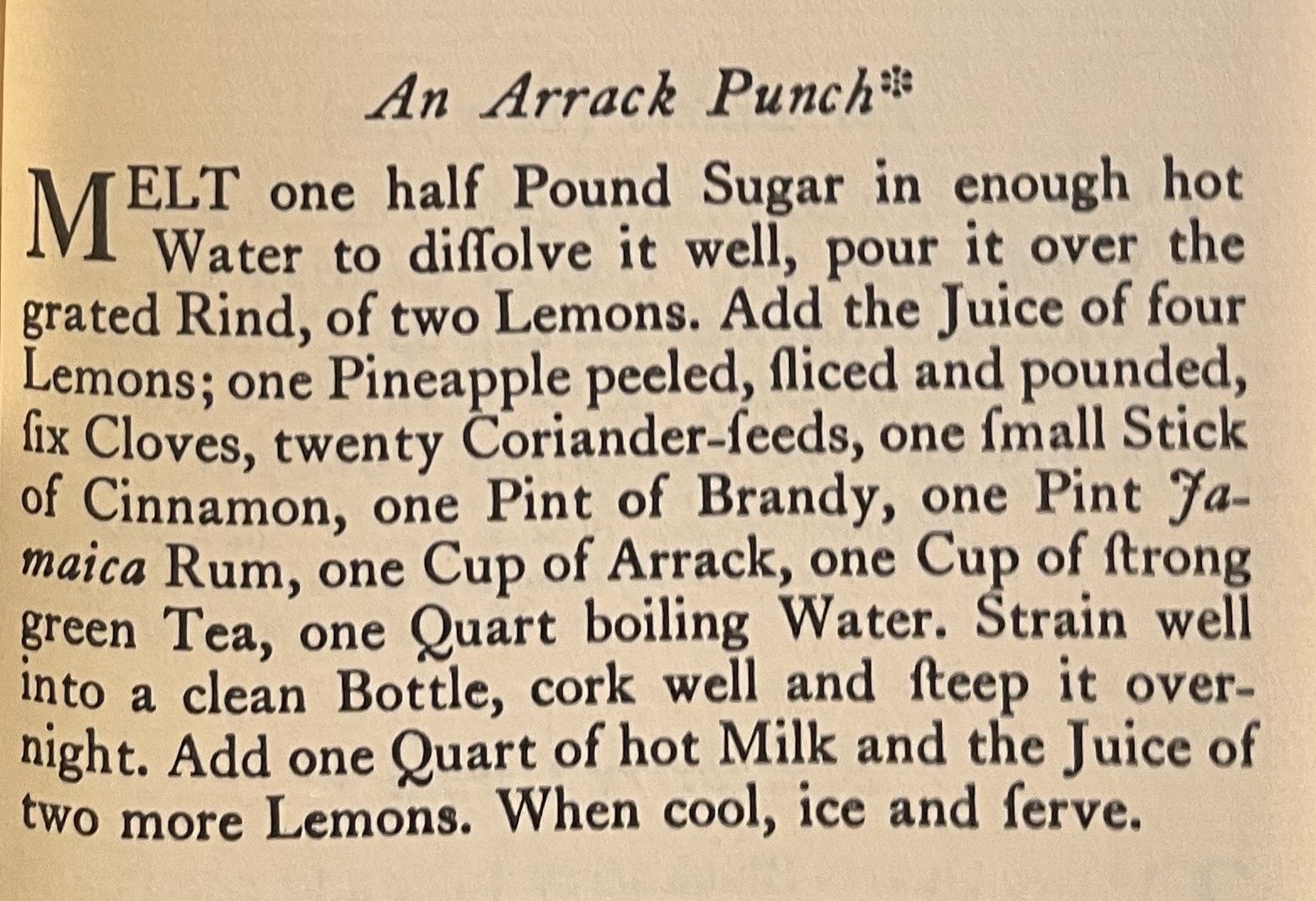

Bullock, Helen, The Williamsburg Art of Cookery of Accomplifh'd Gentlewomen's Companion, Colonial Williamfburg, by The Dietz Press, Richmond, Virginia, 1987.

Earle, Alice Morse, Stage-Coach and Tavern Days, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1900.

Harvey, Karen, Barbarity in a Teacup? Punch, Domesticity and Gender in the Eighteenth Century, Journal of Design History, Oxford University Press, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Autumn, 2008), pp. 205-221, available on JSTOR, Autumn, 2008.

Tamarin, Alfred and Glubok, Shirley, Voyaging to Cathay, Americans in the China Trade, The Viking Press, Inc., New York, New York, 1976.

Comments ()