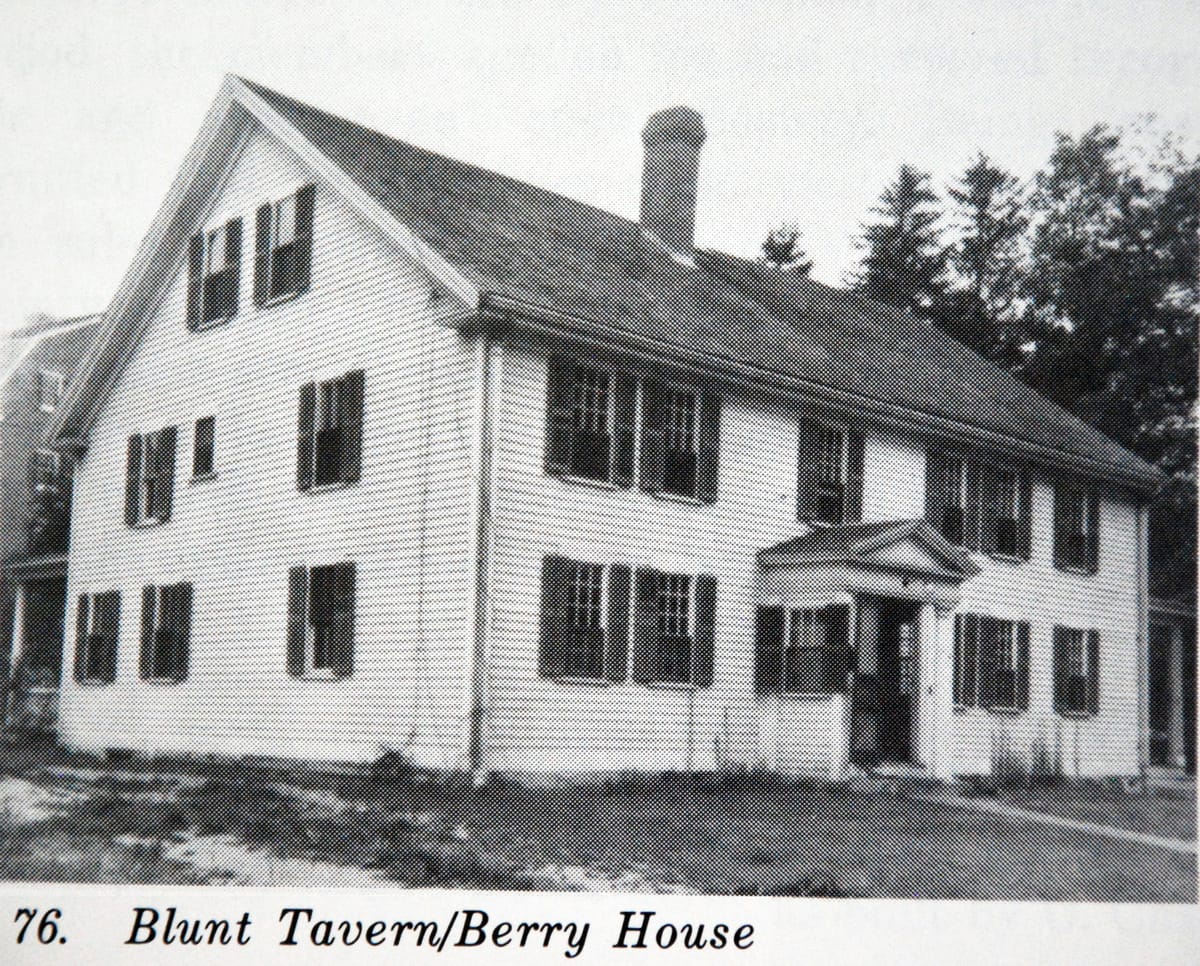

Blunt Tavern: Colony to Young Nation

In many ways, the Blunt Tavern met a fate like that of the Jenkins Post House when the railroad arrived in Andover, MA, in 1832. By 1833, Captain Isaac Blunt and his son, Major Samuel Phelps Blunt, found themselves grappling with debt stemming from mortgages, debts, and taxes on their extensive estate. However, their experience in the tavern business set them apart. While Jenkins constructed a house to cater to stagecoach traffic, the Blunts had already embarked on their tavern venture 40 years before formal stagecoach services began.

Who is Isaac Blunt?

Isaac Blunt was born in 1712 and is from third generation Andover family. His father, William Blunt, born in Andover in 1671, continued the family's local legacy. Despite not inheriting significant property, Isaac successfully established a business manufacturing felt and hats, using the profits to invest in land.

Isaac Blunt entered matrimony twice. His first marriage took place on April 8, 1746, to Mary (Abbott), the widow of Joseph Chandler of Andover, who passed away on April 20, 1760, at the age of thirty-five. Seven months later, Isaac remarried another widow, Mary (Kimball), previously married to Edward Herrick, on Nov. 27, 1760. Both Mary's had connections to taverns — Joseph Chandler's great-uncle owned the Horseshoe Tavern, and the Herricks operated a tavern on Gage’s Ferry Road in Methuen, MA. Armed with their tavern expertise, Isaac and Mary (Kimball-Herrick) Blunt established a "bar-room" in their home around 1764.

The Blunt Tavern is born

With no taverns remaining in Andover’s South Parish after the closure of the Horseshoe Tavern almost thirty years earlier, and with a distance of over 3 miles to the North Parish, Isaac Blunt found himself in an ideal location for his tavern. Nestled along the 'Way to Boston' Road, the Blunt Tavern naturally became a favored stopping point for patrons working or residing in South Parish, as well as for those journeying southward to Boston. (The trek to Andover’s Old Center in the North Parish took between 30 to 60 minutes.) In this era of limited competition and with colonists at the peak of their consumption habits, Blunt was enjoying the 'hay-day' of tavern life.

Big changes were on the horizon. Over the next decade, Blunt encountered competition in South Parish, with rivals like Ebenezer Poor (before 1769), Hezekiah Ballard (1771), Benjamin Ames (1772), and Isaac Abbot (1776). While it remains unclear where and when Col. James Frye operated his tavern, records suggest he was in the tavern business in the 1760s.

The Way to Boston Road's origins traces back to the 17th century, solidifying its status as the primary route to Boston throughout the 1700s. As stagecoach traffic and manufacturing burgeoned along the Shawsheen and Merrimack Rivers, additional north-south routes emerged in the late 1700s. The Essex Turnpike (now Rt. 28) began taking shape around 1803, while Jenkins Post House (circa 1807) supported the Eastern Stagecoach Company. All these establishments were eventually impacted by the railroad, but before we delve into the 1800s, let's delve into the story of our beloved Blunt Tavern.

Taverns and the Revolution

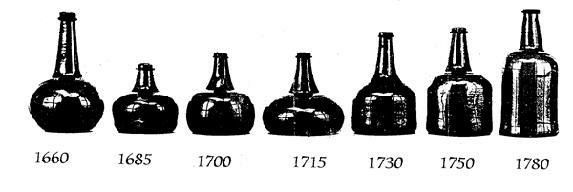

Mary Blunt, with her wealth of experience as a tavern owner, found the perfect spot for the Blunt Tavern, strategically positioned for a steady stream of patrons. However, the mid-1760s marked a fascinating yet challenging period to venture into the tavern business. The demand for rum, beer, and cider was soaring, reaching unprecedented levels. This surge followed the collapse of the 1733 Molasses Act, leading Parliament to introduce the Sugar Act in 1764 -just as the Blunts built their new home with its bar-room.

For over a century, New Englanders had engaged in trade with the West Indies to obtain sugar, molasses and rum. Boston became known for producing New England Rum, a cheaper rum than from the British Colony of Barbados. The Molasses Act's failure prompted pirates to seek other Caribbean Islands, such as the French Colony of Martinique, to evade taxes. Strikingly, tax collections decreased. Responding to the pleas of Barbados, the largest colony in the Hemisphere, Parliament implemented the Sugar Act in 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765. Both measures faced widespread opposition, particularly in Boston, where the economy heavily relied on trade with the West Indies and the production and supply of rum. Adding to the mix, colonists were consuming alcohol at a considerable rate, with some indulging in 5-7 glasses of alcoholic beverages daily.

In the wake of the Stamp Act, the summer of 1765 saw the formation of the Sons of Liberty, swiftly creating a new demand for taverns while also ushering in a wave of violence in Boston, marked by increased effigies, tar-and-feathering incidents, and property destruction. Interestingly, in Boston, more than twenty out of the ninety licensed taverns were owned by members of the Sons of Liberty. These taverns served as crucial meeting spots for the Sons of Liberty and gathering places for any spirited parades.

Although Andover sympathized with the cause, the town was hesitant to emulate the tumultuous behavior witnessed in their southern neighbor, Boston. In response, the Town issued an order to Mr. Samuel Phillips, urging him to "use your best endeavors in conjunction with the other members of the (Massachusetts) General Court to suppress all riotous unlawful acts of violence upon the persons and substance of His Majesty’s subjects in the quarter."

Notably, Samuel Phillips, who would later become a neighbor to the Blunt Tavern, was an early supporter of the patriotic cause, expressing his views on "Liberty" through various writings. Phillips was appointed to represent Andover at the Convention of Delegates. However, before their work concluded, news arrived that two regiments of the King’s soldiers had landed at Boston Harbor in September 1768 to enforce the Stamp Act. In response, Phillips returned to Andover to disseminate this crucial information.

This marked the onset of the decline in rum and its production not just in Boston but across the colonies. The strain of British occupation in Boston ignited significant events, including the Boston Massacre in 1770, the Boston Tea Party in 1773 (organized in the Green Dragon Tavern), and the Battle of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. As British regiments gradually tightened their grip on Boston, trade ground to a halt, causing the flow of West Indies rum and molasses to dry up. A colonial estimate suggested that distillers in Boston were losing a staggering $6,000 in income every week.

Blunt grappled with the dwindling availability of rum, especially affordable New England rum, as the Massachusetts Bay Colony faced trade restrictions in the lead-up to the Revolutionary War. Four new taverns emerged in the years leading up to the Revolution. This is truly a turbulent time for the Blunts.

Changing Neighborhood

Blunt's barroom, positioned near the south corner entrance of his house, became a hub for discussions about Boston and the new taxes. Samuel Phillips, the Andover representative, mill owner, and founder of Phillips Academy, lived in close proximity to the Blunts. It's likely that he shared insights from Boston while engaging in conversations in the barroom.

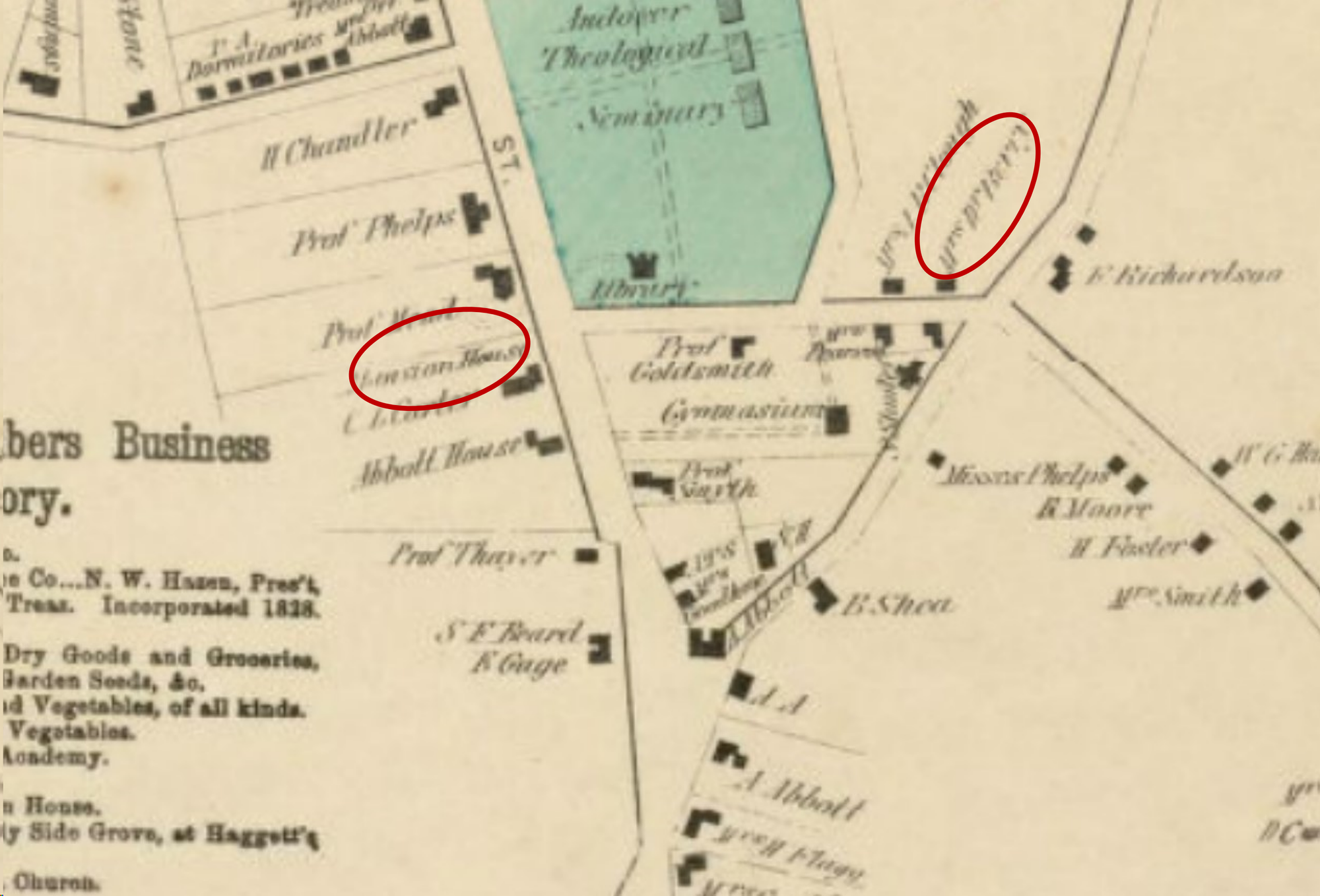

The Blunts also provided a venue for Training Day, now the site of Phillips Academy's famous bell tower and marked Prof. Goldsmith on the map above. Samuel Phillips, Jr. initiated Phillips Academy next to Blunt's Tavern in 1778, making it the oldest academy school in the United States. By this time, it appears that the Blunt Tavern may have transformed into an inn, possibly to accommodate the increased visits to the Academy. While Blunt didn't initially sell land to Phillips, from 1784 to 1830, the Blunts sold several pieces of land to Phillips Academy, including the current Bell Tower site.

In 1782, Samuel Phillips became a neighbor of the Blunts when he began constructing his grand house, aptly named The Mansion. This three-story marvel drew spectators who not only observed its construction but also enjoyed beverages at the Blunts. The Mansion was completed four years later.

In 1789, a momentous occasion occurred when President George Washington visited Andover and toured Samuel Phillips and The Mansion. Washington relished watching the troops on the green in front of both The Mansion and Blunt's Tavern. Following the tradition of having an elm tree, known as a Liberty Elm, in front of a tavern, Isaac Blunt's son, Captain Isaac Blunt, planted an elm obtained from Newbury. Although believed to have been planted in 1790, I suspect it was done in recognition of Washington's visit in 1789. The practice of planting trees on special occasions was common, and this indeed, qualified as a truly special occasion.

The end of the Blunt Tavern

In 1795, Isaac passed on the reins of the tavern to his son, Capt. Isaac Blunt, just three years before his passing at the age of 86. Sadly, within a few short years, around 1803, a group of forward-thinking businessmen banded together to form a company that birthed the Essex Turnpike (now Main St, Andover). The project kicked off in 1805, and by 1807, the General Court greenlit the Andover Company to manage a toll gate. However, the toll didn't sit well with travelers, leading to its unpopularity and, coupled with a lack of travelers, no dividends were ever paid to the stockholders. The Mansion and Phillips Academy were positioned along the newly minted Essex Turnpike, with Blunt’s Tavern just a block away. The decline in travelers undoubtedly took a toll on the Blunt Tavern.

Yet, the real blow to Blunt’s Tavern came with the advent of rail travel servicing points north in 1833, eliminating the need for travelers to stop in Andover for rest or refreshments. By this time, ownership had shifted to the third generation, Maj. Samuel Phelps Blunt, who inherited the burdens of mortgages, debts, and taxes. Consequently, the Blunt Tavern faced an auction. On November 29, 1834, after 70 years as a tavern, it was sold and faded into history. The Blunt family moved to one of their other houses, and eventually, after passing through various owners, the Blunt Tavern met its end when it was torn down in 1930.The property was eventually sold to Phillips Academy in 1950.

Much like Jenkins Post House, the final chapter for the Blunt Tavern unfolded with the arrival of the railroad and the demise of the Eastern Stagecoach Company, both contributing to the dwindling traffic to Andover. However, unlike the Jenkins Post House, Blunt’s Tavern stood witness to the challenges before, during, and after the Revolution. From the changing tides in the supply of rum to spirited political discussions and the remarkable experience of President Washington observing troops from its front step, the Blunt Tavern stands as a true representative of the transition from a colony to a burgeoning new nation – embodying both the triumphs and tribulations of the journey.

Sources

Andover Center for History and Culture, write-ups and photos of Blunt Tavern, https://www.andoverhistorical.org/.

Andover Historic Preservation Site, write-ups and photos of Blunt Tavern, Welcome to the Andover Historic Preservation Web Site | Andover Historic Preservation (mhl.org).

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Drake, Samuel Adams, Old Boston Taverns, Cupples, Upham, & Company, Boston, 1886.

McCusker, John J., The Rum Trade and the Balance of Payments of the Thirteen Continental Colonies, 1650-1775, The Journal of Economic History, Cambridge University Press, March 1970.

Comments ()