Building Andover

Construction in Andover began at least by 1643, an impressive three years before the town was officially incorporated. During this time, the Abbotts and Chandlers played active roles in the construction trades, contributing to the town's development. In 1643, George Abbott constructed a "log-house," a simple post-and-beam structure with wooden siding. In December of 1646, George married Hannah Chandler, the older sister of Thomas and William, who would later become the tavern keeper. George, born in England in 1615 and having immigrated from Yorkshire, had traveled to Roxbury, where he lived for several years before his relocation to Andover and marriage to Hannah. While it is unclear if Abbott moved to Ipswich like some others, his move to Andover and marriage to Hannah strengthened the relationship between the Chandlers, Danes (stepfather's family), and Abbotts.

In 1643, a young man named Thomas Chandler, just 15 years old and the brother of our future tavern keeper, apprenticed as a blacksmith in Ipswich. By 1646, when he turned 18, Thomas was considered a Firstcomer to Andover. He completed a relatively short three-year apprenticeship, shorter than the traditional seven-year apprenticeships in England. Once in Andover, Thomas acquired property adjacent to his brother-in-law, George Abbott, after marrying sister Hannah. Completing their new home in 1647, George and Hannah began their life together. Thomas likely lived with his sister and brother-in-law until he was older and had a place of his own. Later, Thomas would go on to build an iron furnace in Andover, employ multiple apprentices, and accumulate wealth.

Another significant figure in the construction scene was William Chandler, our future tavern keeper. He initially worked as a brickmaker and owned the clay pits before transitioning into the hospitality business. Having control over the natural resources required for brickmaking proved beneficial not only for William but also for the entire community. During the first 15 years (1646-1659), as more than 30 new homes were built in Andover, the demand for bricks skyrocketed. For instance, a modest hearth and chimney alone required over 1600 bricks, while a large center back-to-back chimney needed over 4000 bricks.

Brickmaking was a seasonal occupation due to the unsuitable conditions of wet springs and cold winters for drying bricks or digging clay from the pits. The process involved digging and preparing the clay, molding up to 200 bricks per day (or up to 1500 per day with assistance), followed by a drying period of two or more weeks. Additionally, a kiln had to be constructed to accommodate 2000 to 10,000 bricks, and wood had to be gathered for firing, requiring constant monitoring of the kiln's temperature, which reached up to 2000 degrees. Thus, producing enough bricks for just 1-3 houses was a 3 to 4-month endeavor. Brickmaking was a skilled trade, although physically demanding. Bricks had to conform to regulated sizes, necessitating the use of mold boxes with metal bands to maintain their shape. Firing the bricks was a crucial step to ensure their usability. William's first trade kept him occupied and provided a good income.

In addition to the impressive skills of the Chandlers, the early settlers in Andover included talented builders like the Barkers, Osgood’s, and Jacques, as well as a skilled millwright named Parker. There is speculation that Bradstreet had an early sawmill as early as 1644, which played a crucial role in producing the lumber needed for the initial homes and even for trade, possibly to places like Barbados (perhaps for rum?). Skilled labor, such as that of a millwright, commanded a higher price in 17th-century Massachusetts. By 1700, with the influx of immigrants and a booming economy, almost every town in Massachusetts had a sawmill. However, it's important to note that not all sawmills were the same. Some were simple structures valued at £10 (equivalent to the value of a one-room house), like the John Elderkin mill in Reading, built in 1646 (50% interest was £10). On the other hand, the Colby mill in Salisbury was much more elaborate, valued at £240 in 1660. When Joseph Parker of Andover passed away in 1678, he left behind a "corne-mill" on the Cochichewick River to his son, valued at £20 – not much more than the price of a two-room house. While it remains uncertain if this mill was the same as the 1644 Bradstreet mill, what we do know is that Andover possessed the necessary skills and resources (abundant trees for lumber, water to power the mill, clay for bricks, and peat bogs for iron production) required to become a remarkably prosperous town. In just a few short years, Andover thrived and flourished.

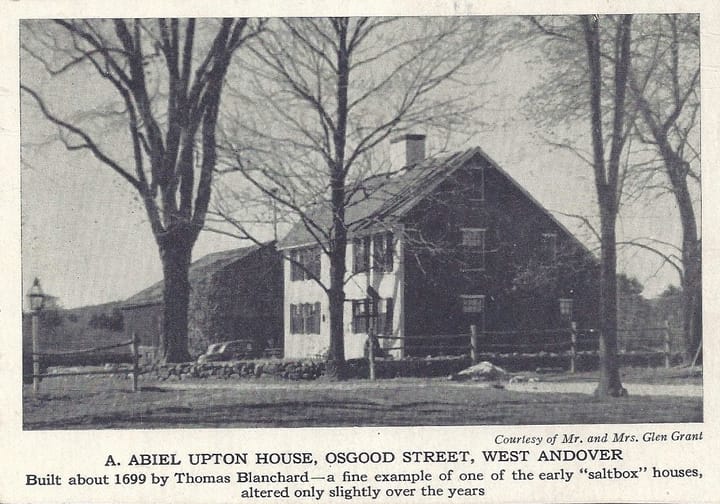

The early settlers of Andover brought with them a wealth of tools, skills, and building techniques acquired during their apprenticeships in England. Many of the prominent building families in Andover hailed from Wiltshire or Hampshire County, such as Christopher Osgood, Henry Jacques, and Samuel Blanchard, and they applied the architectural designs they knew to the construction here. While architectural styles naturally evolved over time, it can be assumed that these builders adhered to tried-and-true techniques. As one historian aptly put it, "the earliest settlers had limited time and resources, allowing them to construct simple one-room houses with a chamber above. The fireplace was situated at the gable end, accompanied by a newel staircase between the hearth and the entrance." During the 17th century, "the typical Wiltshire farmhouse remained a modest rectangular structure, primarily built using timber, with dormers providing light to the upper rooms." The settlers relied on their familiarity with these building practices to establish a sense of familiarity and continuity in their new homes.

Building Andover's first homes

During the early to mid-1600s, houses in Andover were typically small, often starting as single-room structures, sometimes with two stories. The dimensions of these houses, such as 16' x 14', were quite typical. With the arrival of twenty-three new landholders in Andover, the need for new houses and barns to accommodate livestock required significant manpower and resources. These houses were constructed using crude post-and-beam (log) techniques. Since there was no paint available, the buildings had a plain appearance and were often coated with pine pitch tar as a preservative. To provide protection against potential attacks by Native Americans and fire, the houses were frequently reinforced with bricks in the walls. Interestingly, the barns were often larger than the houses.

According to Abbott Lowell Cummings, in Massachusetts Bay Colony, out of the 144 houses surveyed, 82 of them that stood before 1725 were one-room houses. Among at least seventy dwellings, with dimensions mentioned in documents from 1637 to 1706, 39 (56% of the 82 one-room houses) were of a specific variety measuring 16 feet long and 14 feet wide. Only two houses were smaller than fifteen square feet. In terms of value, ten out of thirty single-room houses had a worth ranging from £15 to £163 (between 1638 and 1650), while twenty-three out of thirty two-room houses were valued between £112 and £1,506.

In Andover, much like in other parts of Massachusetts Bay, most houses started as one-room or one-over-one configurations. The Robert Gray Jr. house on Salem Street, believed to have been constructed around 1705, is the only surviving first-period one-room house with dimensions consistent with Cummings' findings (17 feet long and 13 feet wide). It's intriguing to imagine how they managed to accommodate a large family in such a small space.

The typical one-room house plan remained relatively consistent into the eighteenth century. Out of the fourteen existing Andover homes built between 1660 and 1700, ten (72%) started as one-room houses or one-over-one room houses. The remaining 28% consisted of two-room configurations, with three or four two-over-two room homes. At 168 Osgood Street, it is believed to be the site of Simon Bradstreet, the wealthiest man in town and future Governor of Massachusetts Bay. The foundation found there measures 35' x 18', indicating the presence of two rooms on the first floor and likely a second story for a person of such wealth. This is likely what we call a Colonial-style house today.

Who had the first Tavern?

Every town in Massachusetts Bay was required to have a licensed ordinary or place to buy strong liquors - beer, wine, or later rum. The Ordinary was more than a place to buy a drink, it was a place to have a meeting, get the latest news, or to do business. Ordinary keepers and vintners were subject to various regulations, including licensing, beer costs, malt content, and alcohol strength. The 1651 law stipulated that a hogshead of beer had to contain six bushels of malt to be sold at 3d. a quart, four bushels for 2d., and two bushels for 1d. To maximize profits, keepers would often dilute their beer. Surprisingly, it appears that no brewer in seventeenth-century Essex County was fined for diluting beer or brewing with Indian corn, oats, or rye.

Mr. Edmond Faulkner, who negotiated with the Native Americans to "buy" Andover in 1646, holds the distinction of being the town's first licensed vintner. During that time, a vintner was similar to a modern liquor store, specializing in the sale of strong liquors. According to the Faulkner family legend, Edmond Faulkner offered rum to the Native Americans to "assist" the negotiations. The entire story of procuring the Andover land, which cost £6 and a coat, raises thought-provoking questions about the relationships between Native Americans and settlers in the 1640s.

In 1644, Passaconaway, the leader of the Pennacook Confederacy, including the local Pawtucket band, agreed to a "treaty of subordination" after his son was held captive. Massachusetts Court records indicate that the sale of Andover was negotiated by Cutshamache, the Massachusetts sagamore, but his band resided south of Boston and was not a part of the Pennacook Confederacy. The entire process of "buying" Andover appears dubious.

Adding to the suspicious circumstances surrounding the trade, the first fully recorded history of rum in the Americas dates back to 1650, making it unlikely that Faulkner had access to rum as early as 1646. This family legend remains historically uncertain at best, but it does provide some insight into Faulkner's character and actions.

Faulkner's home, which served as a liquor store, was likely a one-room house. While he was not necessarily an ordinary or tavern keeper, Faulkner held the only license of its kind in town. His primary offerings were beer, with the addition of perhaps some rum or wine. Considering Andover had only 23 families and homemade hard cider was on every dinner table, one may wonder about the success of Faulkner's business. As expected, his venture did not last long, as by 1653 - only 5 short years after getting licensed, Faulkner's business was closed, and Andover faced fines for lacking an ordinary.

In 1654, Deacon John Frye became a licensed retailer of strong liquors, possibly marking the early introduction of rum to Andover. Deacon Frye was likely a customer of Simon Bradstreet's lumber trade with Barbados. John Frye played several important roles in the early years, including being one of the ten freeholders required to organize the Church of Andover, established on October 24, 1645. Both John Frye and his son John served as Deacons, further solidifying their esteemed positions in the community and obtaining a license to sell liquor.

It wasn't until 1687 that Andover officially had a licensed tavern. William Chandler, at the age of 51 and 40 years after Andover's incorporation, received the first Ordinary license. The delay raises questions: Did Andover truly wait this long, or did William operate an Ordinary without paying for the license? Stay tuned for the next episode to find out!

Sources:

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880

Cummings, Abbott Lowell, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1979

Comments ()