Part 2 - The Horseshoe is in Trouble

In this episode, we'll explore the years of turbulence before and after the licensing of the Horseshoe in 1686. Alcoholism, ethnic biases, tensions over land distribution policy, the King Philip's War, and Andover's first murder led to divisions among the population. At the center of these divisions is the newly licensed Horseshoe.

The firstcomers to Andover consisted of 23 individuals, including two Chandlers - Thomas Chandler and his sister, Hannah Chandler Abbott and soon after, William and his stepbrother, Francis Dane. For over 10 years, the Danes, Abbotts, and Chandlers had been sharing a journey from Hertfordshire County in England, across the Atlantic, to homes in Roxbury and then Ipswich before finally settling in Andover in the late 1640's.

So, what was Andover actually like in its early years? Andover's center was built around a town green and meetinghouse, creating a close-knit community with protected homes and strong friendships. However, biases were not absent. The Southwesterners from England occupied the "North End" of this tightly built community, while the Hertfordshire County residents and Scots resided in the "South End." The Southwesterners held higher social rank and were granted larger house lots. Each person who received a house lot grant was also allocated 20 acres of pasture and tree lots, typically located at a distance (miles) from their homes. By the fourth and final allocation in 1662, those who owned the original 20-acre house lots had amassed a total of 610 acres, whereas owners of four-acre house lots, like William Chandler, had a total of 122 acres by 1662.

EARLY ANDOVER LIFE

During the 1650s, Andover experienced rapid growth. Families settled down, built homes on their house lots, farmed the pasture lands, attended Sunday meetings, and engaged in local trade. They traded land, bartered for work, and even had international trade, with Bradstreet's sawmill trading as far as the West Indies (sugar, molasses and rum). Thomas, a blacksmith and ironworker, and William, a brickmaker, were both busy in their respective trades while also building their families.

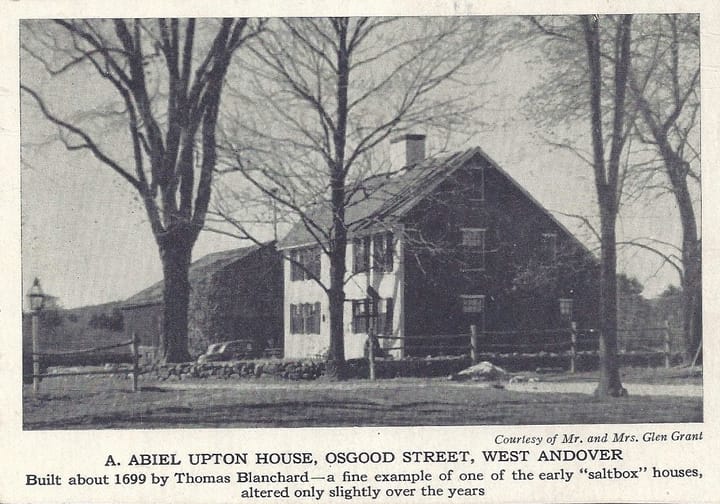

Apart from the sole liquor license, another sign of a tavern was the mandatory Training Day. Training Day took place monthly and served as a militia practice, with every able man required by law to attend. By 1658/59, John Osgood (2), a Southwesterner, was listed as Andover militia's first sergeant and later rose to the rank of Captain. He also served as a selectman and eventually obtained the second ordinary license, after the Horseshoe. Training Day was beneficial for business and likely marked the early beginnings of the Osgood Tavern, which officially obtained its license in 1686, many years later.

While this idyllic picture is painted, tensions were brewing. In 1662, the final land allocation occurred, prompting Andover to reconsider its land distribution methods. By 1675, the town decided to shift from simply allocating lots to newcomers or the next generation, and instead started selling 20-acre lots for 10 shillings each, half in value of wheat and half in Indian corn. Although this was a nominal amount, it had to be paid annually and sparked a lively discussion at the town meeting on January 4, 1675.

During this turbulent time, notable firstcomers such as Nicholas Holt, Thomas Chandler, and George Abbott decided to leave their original house lots in the Center and settle in South Parish. Holt headed due south of the Center to Holt's Hill along Salem Street (Way to Reading), Chandler went due west along Billerica-Ipswich Way, and Abbott moved southwest near Roger's Brook. Each are now miles from each other and the Center. Recognizing the need to address land issues in South Parish, the town selected William Chandler in 1677 to survey the area.

In addition to the land allocation issue, which affected the ability of the next generation to have sufficient land to support their families, the onset of King Philip's War was imminent. Peace had prevailed for a long time until a change in Indian leadership. The Indians launched attacks on Springfield in September and Deerfield in October of 1675. Throughout the winter of 1675-76, numerous attacks occurred as the Indians attempted to annihilate the colonists. It was during this time that George and Hannah Abbott made their move to South Parish in April 1676, settling across from the soon-to-be new meetinghouse in South Parish (now Central Street). On the same lot, there is an old structure dating back to the 1660s. Shortly after their move on April 8, 1676, tragedy struck the Abbott family when their son Joseph, aged 25, was killed by Indians. Another son, Timothy, aged 13, was taken captive but later returned by a friendly Native American woman in August after enduring hunger and hardship.

Where is the Horseshoe tavern located? The 1686 Horseshoe license states that it was situated 1-1/2 miles away from the other ordinaries (Faulkner and Osgood) along Billerica-Ipswich Way, making it convenient for travelers. This aligns with real estate records indicating that Chandler's ordinary and home was along Milk Street, not far from the town green, on land he acquired through a trade with the Ballards. With his brother Thomas Chandler and brother-in-law George Abbott already moving to South Parish in the 1670s, one may wonder why William chose to stay in the Center. I suspect that practical reasons played a role. Being a brickmaker, William was close to the clay pits situated just south of his home, and the proximity to foot traffic was advantageous. He already had an ongoing tavern (although not officially licensed until 1686), and considering the Indian uprisings, staying close to the town Center provided a sense of safety.

William's prosperity became evident from early on. By 1679, his brother Thomas was the top taxpayer in the South End, with William ranking fourth. Interestingly, the top four taxpayers in the South Parish were all related through marriage, sharing common roots in Hertfordshire County, gathering around Minister John Norton's Company in Ipswich, and now congregating in the South Parish. In the same year, William Chandler served on the board of selectmen, faced the tragic loss of his first wife during childbirth, and later remarried Bridget Richardson from Chelmsford. It is also the year Andover implemented a 9 o'clock curfew.

THE ROWDY HORSESHOE TAVERN

In 1679, Andover implemented a curfew to restrict late-night activities involving drinking, playing games, and causing a disturbance. This decision was likely prompted by an incident involving William Chandler's nephew, who shared the same name and was the son of Thomas Chandler. In August of 1678, a fight ensued between young William Chandler and Goodman Wright, a wheelwright. The disagreement stemmed from a horse causing trouble in the fields, and it escalated into a knife fight, leading to a court appearance. It is believed that both individuals were under the influence of alcohol during the quarrel, although it is unclear where they had been drinking. Nevertheless, it can be inferred that the introduction of the curfew was a response to the disorderly behavior associated with establishments like the Horseshoe - where the Chandlers gathered for a drink.

With the establishment of the curfew in 1679 and William Chandler's marriage to Bridget in the same year, it is likely that Chandler's house became a place of entertainment and business. It was also the only establishment owned by a resident from the South End. For instance, in 1681, Andrew Allen, a relative by marriage, held a meeting at William Chandler's residence with men from Chelmsford to negotiate marriage arrangements for their children. Chandler's Horseshoe Tavern had already become a gathering place, even before obtaining an official license in 1686. These meetings served as, yet another example of how Scottish and old Hertfordshire families connected, married, and supported one another within the community.

Were the residents of the South End too rowdy for the Puritan leaders in the North End? In 1688, just a few years after obtaining his "official" tavern license, William Chandler faced complaints from 35 citizens, representing over 20% of Andover's population at the time (~600 people), about the "evill" taking place within his establishment. The petitions revealed that there was an abundance of alcohol, including strong liquor (rum), numerous intoxicated individuals, late-night gatherings, games, and frequent toasting.

Andover's first murder

These complaints resurfaced in 1689, with additional grievances stating that Chandler allowed young and impoverished individuals to squander their time and money at the Horseshoe Tavern on barrels of cider and strong drinks, presumably rum. However, if the 1679 curfew was initially imposed due to activities at Chandler's house, why did the interest in closing his tavern resurface ten years later? The primary reason was the recent and tragic murder that occurred in Andover. On April 20th, 1689, Hannah Stone was murdered by her intoxicated husband, Hugh, after 23 years of marriage and seven children. Cotton Mather documented that Hugh, a Scot, was drunk and engaged in a quarrel with his wife regarding the sale of a piece of land, which ultimately led to him slashing her throat. This dreadful incident took place within the Scottish community, involved alcohol consumption, and likely took place near Chandler's tavern, which was located next to the Scottish community. Hugh Stone was executed for his crime, and on the gallows, he issued a warning about the dangers of alcohol.

"an epidemic of evil"

The Stone murder had a significant impact on the town, motivating residents of the North End to take action. By March 1690, less than a year after the murder, concerns were already mounting regarding the excessive consumption of alcohol in Andover. Although a curfew had been in place since 1679, William Chandler's Horseshoe Public House was again petitioned by 35 fellow citizens for allowing drunkenness, providing loans to patrons so they could drink more, and staying open past midnight. The complainants decried "all manner of Excess and Disorder" taking place at Chandler's tavern, the Sign of the Horseshoe, warning of an epidemic of evil that threatened to corrupt a significant portion of their town if not promptly addressed. Some of the complaints raised against William Chandler's tavern were as follows:

“his forwardness to promote his own gaine he hath been apt to animate and to entice persons to spend their money & time to ye great wrong of themselves and family.”

Tavern keepers had various ways to boost their profits, including diluting the alcohol since the serving size was fixed. Another common practice was to promote drinking, such as the tradition of "drinking to your health."

Another complaint revolved around the presence of servants and children in the tavern at all hours, including late into the night, well past the 9 pm curfew. Laws of the time restricted the presence of slaves, indentured servants, and children in taverns, similar to today's regulations prohibiting children from sitting at the bar. However, court records indicate that such rules were not always followed, with complaints noting the occasional presence of eleven- and twelve-year-old girls, often referred to as "children include servants." It will be revealed later that Chandler involved his own children in the tavern's operations.

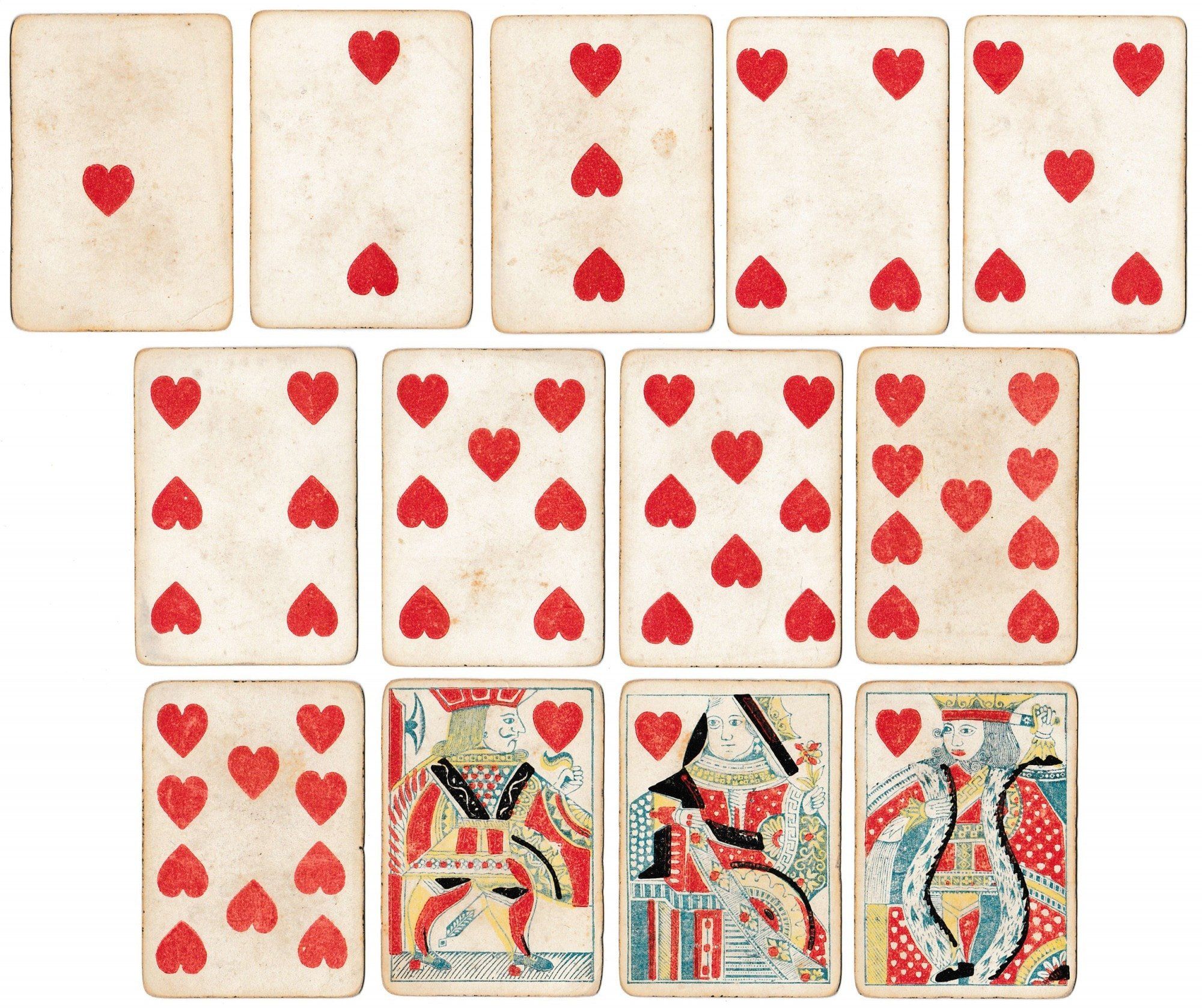

Gaming was another issue of concern, with the complaint stating, “Gaming is freely allowed in his house by which means the looser must call for drink wen is one thing ye will uphold his calling.” Chandler eagerly provided the drinks. Unlawful games such as dice, cards, tables, quoits, loggets, bowls, ninepins, and billiards were specifically mentioned as prohibited in Chandler's license. Interestingly, dancing and other forms of entertainment, including plays, were also frowned upon during that time. In fact, in 1687, Judge Sewell in Boston condemned tavern keeper John Wing for adding seats to his tavern and hosting a play, as plays were considered indecent.

Lastly, there was a worry that the younger generation was being corrupted by the tavern's influence, leading to a course of drunkenness among them. While the exact nature of the issue was unclear, it was likely related to serving rum to the young and allowing them to become intoxicated. Children were often exposed to cider from an early age, even if it was diluted to create "cyder-kin." Beer and cider were commonly served during meals, and rum punch and Flip (a combination of rum and beer) were popular and enjoyable beverages for both the young and old.

These complaints shed light on the concerns and controversies surrounding Chandler's tavern, painting a picture of the activities that took place and the impact they had on the community, particularly the younger generation.

But once again, William Chandler's friends took the initiative. Due to Chandler's inability to engage in strenuous labor (was he unhealthy?), the court renewed his license "to keep a common house of entertainment and engage in the common selling of ale, beer, and cider in his Dwelling House, known by the sign of the horseshoe." The petition for renewal was successfully passed, with signatures from Mr. Dudley Bradstreet, Thomas Chandler, Henry Holt, John Abbott, and John Ballard. Four of them were related to Chandler, and Bradstreet was someone he knew from his days in Ipswich.

Osgood and the 35 petitioners were concerned about the escalating issue of alcoholism in town. Thomas Johnson, a constable, faced charges for "allowing a barrel of cider to be drunk in his house at unseasonable hours by young people." Additionally, one of the town treasurers appeared before the court for drunkenness and disorderly behavior. Mr. Dudley Bradstreet, the magistrate, described it as "some weakness that overtook him."

It is evident that there was growing tensions in Andover with leading citizens leaving the center, Indian attacks, numerous petitions, the need for a curfew, and the murder of Hannah Stone. As the renewal of Chandler's license shows a lot of this tension is centered around the Horseshoe. In our next episode, we will see how William Chandler addresses this increasing pressure.

Sources

Abbot, Elinor, Our Company Increases Apace, History, Language, adn Social Identity in Early Colonial Andover, Massachusetts, SIL International, Dallas Texas, 2007.

Abbot, Elinor, “Transformation: The Reconstruction of Social Hierarchy in Early Colonial Andover, Massachusetts”, 1989.

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston 1880.

Greven, Philips F. Jr, Four Generations: Population, Land, and Family in Colonial Andover, Massachusetts, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 1970.

Diary of Samuel Sewall in Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 5thSer., V (1877).

Andover Town Records, January 4, 1675.

Comments ()