Explore the road system of the 1800's at Forgotten Taverns. Stagecoaches became obsolete with the growth of railroad as did the roads they traveled. #ForgottenTaverns

Some old homes are on busy streets, while others are in remote locations. The Benjamin Jenkins Post House which opened in 1807, is in a remote location. After 28 years as a stagecoach stop, Benjamin died. His widow, Betsey, faced other challenges times with the advent of early railroads in 1835 and the subsequent collapse of the Eastern Stage Company by 1838. This period undoubtedly presented hardships for the post-house and it likely closure by 1836. Like the remote nature of Route 66 today, this historical narrative reflects a common theme —a tale of going from prosperity to decline, echoing the prevalent challenges of an era.

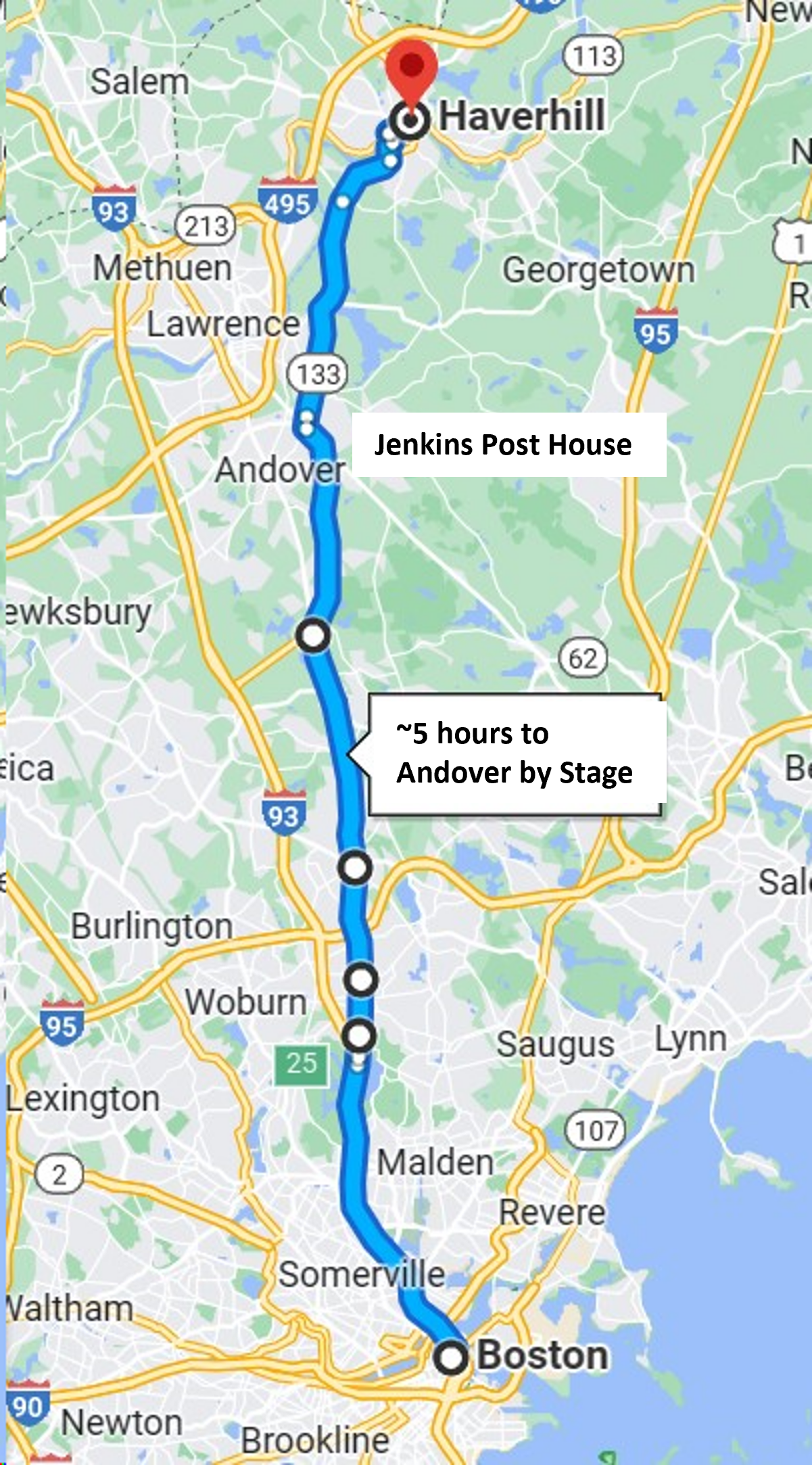

Road from Boston

The Eastern Stage Company mapped the shortest and most direct route north, avoiding any additional costs for their stagecoach line. Once leaving Jenkins, the post road continued north and crossed over the Merrimack River using the Andover Bridge into Haverhill. Given the destruction of the Andover Bridge in 1807 due to a flood, the stage started using the Bradford Bridge as shown on the Google Map. After the flood of 1807, the Andover Bridge was rebuilt further upstream (west). At different times, each bridge would be used based on availability as they were often impacted by storms and needed to be reconstructed. However, that was about to change as traffic demands shifted.

Mills located to the west of the post road along the Merrimack River found that the drop of the river was better suited for mill production, leading to the prosperity of new mills. With the construction of a toll bridge across the river further west, traffic gradually shifted from the Old Center of Andover (now North Andover) to the west side of town.

To support this growing traffic, The Essex Turnpike Corporation, established in 1803, laid out a toll road (now known as Route 28 or Main Street, Andover) from 1805 to 1810. The toll road extended from the New Hampshire border, and by 1806, it reached the Middlesex County line. A toll station was constructed near this significant boundary line.

With the continuing business from the Eastern Stage Company, Jenkins was not deterred and constructed his post house in 1807. Competing road systems persisted until the bankruptcy of the Eastern Stage Company in 1838, but by this time, Benjamin Jenkins had passed away. Looking at the road today, it is challenging to imagine that it was once a main thoroughfare. When returning home from work, I would frequently use this old stagecoach route to bypass the traffic on the main roads. It is a picturesque road that passes directly through Harold Parker State Forest, featuring few houses and many trees.

Inside the Post House

Insights into the set-up and use of the post-house during his era can be gleaned from Benjamin's probate records.

The first room serves as the typical inventory for the tavern or greeting area, showcasing the unique collection attributed to Bengamin Jenkins. In this space, you'll find more extravagant items than your average tavern room, including silver spoons and carpets valued at $8 and $12, respectively. The remaining furniture in this room is modestly priced at $20. Carpets during this era were handwoven strips measuring 27” to 36” in width, sewn together and secured along the perimeter. Initially woven in random stripes, by 1801, more intricate patterns began to emerge. Notably, this carpet ranks among the most expensive items in the house, second only to one bed, making it a focal point designed to leave a lasting first impression.

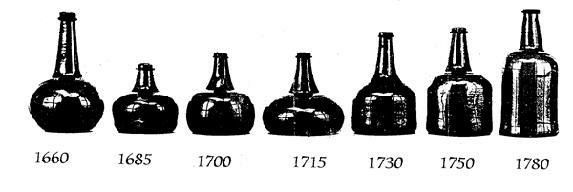

Taverns of the early 1800s were typically furnished with common or simple furniture, as the men were tough on the furnishings—leaning in chairs, placing feet on chairs or tables, and bringing in dirt from the door. Except for the carpet and silver spoons, the inventory lists several expected items such as chairs, tables, a mirror/looking glass for straightening out travelers' hats, and glassware and crockery for crafting liquid beverages. The color scheme is inviting yet functional for heavy wear. Many taverns of the time adorned their walls with striking murals to enhance their appeal even further.

The taverns of the period often served as hubs for social exchanges, with handwritten notices around the chimney serving as a community bulletin board. In 1838, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote about a tavern in Shrewsbury, MA, conveying such messages as, “I have rye for sale” and “I have a fine mare colt” along with “a quaintly expressed advertisement of a horse that had stayed or been stolen from a pasture.”

The next room on our inventory journey is the other front room (located to the right of the front door in the photo). While it includes a bed and bedding valued at $15, this space is likely designated for relaxation, reading, writing, or simply waiting for the stage to depart. The furnishings in this room consist of chairs, a table, a desk, a clock, a trunk, and a carpet. Often referred to as "waiting rooms" or parlors, travelers have noted that these areas were tastefully decorated with finer furniture, carpets, and comfortable chairs, creating a cozy space for reading the newspaper or enjoying a good book. Women could also take their meals here, and businessmen could use the space to write letters or plan their itineraries. These front rooms were often adorned with flowers or other decorations, adding a touch of charm. It's worth mentioning that this room features a bed, likely intended for a quick nap or as overflow on crowded nights.

Moving on to complete the first floor, we encounter three unitarian rooms—the kitchen, the long storage room, and the well room. The kitchen is efficiently organized with items categorized by their materials: iron (pots, pans, tea pots), pewter (plates, pitchers, salts), brown [wood] (pails, buckets, spoons, and paddles), and crockery ware (bowls, pickling). Despite being a bustling hub of activity, the kitchen is furnished with economical items, totaling only $15. The long storage room, as per the inventory, serves to store items like pickles or butter in tin, wooden, and crockery ware, with a total value of $20. The final room on the first floor is the well room, featuring the literal well and hand pump, along with items requiring cold storage, such as cheese, long-term storage of vegetables (squash, potatoes), or drying meats. The well room inventory includes meat chests, bags, and dry casks, amounting to a total of $5.

Bedrooms

The inventory reveals a total of five rooms adorned with beds, with four of them situated on the second floor, summing up to 7 beds in total. Right at the top of the stairs is Jenkins's bedroom, strategically placed at the front of the house. This location provides Jenkins with a vantage point to observe outdoor activities, catch the buzz from the floor below, and bask in the warmth and sunlight of a southern exposure. Termed the "master bedroom," this room boasts an opulent bed and bedding, along with a bureau, table, chairs, and a mirror, all valued at $22.

Moving along the second floor, we come across three more bedrooms. The next spacious room at the front of the house features a bed, a table, mirror, chairs, chests, and a trunk, all totaling $15. This cozy space was likely designated for any traveling women or couples. The third room, a small bedroom, appears to be tailored for children and is modestly furnished, with a value of $15. The final back bedroom is equipped with 3 beds with bedding and a chest, valued at $24, making it suitable for accommodating up to 9 guests. It was a common practice to share a bed with 1-2 strangers, though one could only hope they didn't snore! Additionally, it's likely that the coach driver either shared a room with the guests or had a space adjacent to the kitchen, a customary arrangement for the time.

After a night spent with up to 8 strangers, the stagecoach typically hit the road bright and early the next morning. In her 1836 journal, Caroline Fitch vividly captures the experience, sharing, "The stage was set to leave at four o’clock in the morning, and this idea haunted our broken slumbers. We retired to bed early, frequently checking the watch throughout the night despite the hours being marked by the striking of the town clock. At three, we could endure this tortured sleep no longer. We arose and hardly were the duties of the toilette ended ere the stage was at the door.” I am sure catching up on your sleep on the stage was not easy either with the lack of seat backs and the bumpy ride.

The end of an era

Jenkins’ Post House was established to support the stagecoach and its growing business. For over 28 years, travelers enjoyed the hospitality of the Jenkins. With the death of her husband and a failing business, Betsey faced some hard times. Somehow, she managed to stay in the house until her death 28 years later. The house is now a beautiful private residence along a country road, graced by the trees of Harold Parker State Forest to the south and surrounded by few homes. It is easy to imagine the small dirt road from the old photographs.

Sources

Andover Center for History and Culture, write-ups and photos of Jenkins Post House, https://www.andoverhistorical.org/.

Andover Historic Preservation Site, write-ups and photos of Abbot Tavern, Welcome to the Andover Historic Preservation Web Site | Andover Historic Preservation (mhl.org).

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Fitch, Caroline, Travel Diary, 1836. Old Sturbridge Village Research Library. Edited by Old Sturbridge Village.

Larkin, Jack, Dining Out in the 1830's, Published by Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge MA, 1999.

Comments ()