Disruptive Technologies change Taverns forever.

“Who, in these days when all things go by steam

Recalls the stage-coach, with its four horse team?

Its sturdy driver –who remembers him?

Or the old landlord, saturnine and grim,

Who left our hill-top for a new abode

And reared his sign-post farther down the road?”

In 1878, Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote this poem (The School Boy) to celebrate centennial anniversary of Phillips Academy (Andover). This reflection takes us back to a time when visitors to taverns were mainly locals, strolling in on foot. As the 17th century waned, post riders traversed the roads from Boston, bringing news and mail, halting at designated taverns. However, the early taverns primarily catered to the needs of the nearby residents.

The 18th century brought change and disruption to the tavern business. Improved roads and the introduction of early coaches altered the landscape. "Stage-chaises" served long routes, while "stage-coaches" and "stage-wagons" covered shorter distances. In the years preceding the Revolution, these commercial endeavors transformed taverns. Transient customers, seeking new services, reshaped the demographic of these establishments.

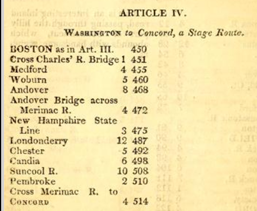

Andover played a pivotal role in this transition, becoming a crossroads for travelers journeying northward. Taverns dotted the landscape, supporting vital routes to key towns such as Boston in the south, Haverhill in the north, and to the east, Salem, the county seat and shipping hub. Taverns, like the Horseshoe Tavern of the 17th century, evolved into the Ballard Tavern and Poor Tavern (see Salem Poor: Slave to War Hero) in the 18th century.

The revolutionary period brought disruptive inventions, including the public stage, altering roads and travel routes significantly. The once-familiar post road shifted, bypassing the center of Andover, following a more direct route from Boston to Haverhill and Portsmouth. But beginning around 1790, a series of changes began that historians have called “The Transportation Revolution of America”. The stagecoach was speeding up transportation driving the need for better road. New Englanders rebuilt and vastly extended their roads. More than 3,700 miles of turnpikes, or toll roads, were built in New England between 1790 and 1820.

And so, the passage of time reshaped not only the roads but also the very essence of the taverns that once welcomed weary travelers. In their tales, we glimpse the spirit of a bygone era, forever etched in the annals of Andover's history.

The Stagecoach

In the early 18th century, the concept of stagecoaches revolutionized travel. The journey began in 1712 at the Orange Tree Tavern, marking the humble beginnings of this mode of transportation. However, it wasn't until 1761 that Bartholomew Stavers established the first public stagecoach route from Boston’s North End to Portsmouth, NH, passing through Andover, Haverhill, and into New Hampshire, specifically through Exeter and Portsmouth.

This route was not just a road; it became a bustling highway, shortening distances and connecting communities. The 'large stage chair' or 'stage-chariot,' drawn by two horses, could comfortably accommodate four passengers. By 1763, the 'Portsmouth Flying Stagecoach' was introduced, a marvel of its time, carrying six passengers at a speed that amazed travelers.

A journey from Boston could be quite grueling, especially in the winter months. To put things in perspective, back in March 1716, the "post" took a whopping nine days for a single trip between Salem and Portsmouth, covering a mere 40 miles.

By the 1770s, the stage service to Portsmouth and onward to Portland, Maine, was operating three round trips per week, departing Boston every other day. This increased frequency marked the true advent of stage service, transforming taverns into more substantial inns. Travelers could now expect provisions for food and drinks, stables for horses, and overnight accommodations.

Now, picture this: a description of a stage-wagon from 1795 paints quite the picture. Imagine a long car with four benches. Inside, three of these benches held a total of nine passengers, with the tenth perched next to the driver on the front bench. A lightweight roof was upheld by eight slender pillars, four on either side. Three sizeable leather curtains, suspended on the roof, could be rolled up or let down according to the passengers' whims. Now, here's the kicker – there was no designated space for luggage; everyone was expected to tuck their belongings under their seat or between their legs. To board, you'd enter from the front over the driver's bench. Naturally, the three passengers on the back seat had to maneuver their way across all the other benches to reach their spots. Oh, and what about those benches? They lacked backs, which made for quite the challenging journey, especially on poorly constructed roads. The back seat was preferred for the back rest and frequently given to the women on the trip.

The drivers of these stagecoaches were remarkable characters – sturdy, hearty, and healthy Yankees, known for their good sense and steadfast habits. They led vigorous lives, their resilience unmatched. A typical driver had to be more than just skilled with the reins; they were astute traders and adept merchants, ensuring the smooth flow of passengers and goods.

The success of the Portsmouth Flying Stagecoach was unparalleled. Its regularity led to its role in carrying mail, earning it the title of 'Flying Mail-Stages.' This service became so ingrained in the society that it became a part of daily life.

Bartholomew Stavers, the driving force behind this revolutionary mode of travel, was a loyalist who eventually returned to England. There, he introduced a similar stage and mail service, inspired by the Massachusetts model. By 1784, England adopted this nationwide, embracing the innovation that had once transformed the landscapes and lives of American travelers.

The Tavern

Flash forward to 1781, and a stage was making the rounds from Boston to Portsmouth (and beyond to Portland), passing through Andover, Haverhill, and venturing into New Hampshire via Exeter before finally reaching Portsmouth. This route was direct, and, thanks to early well-built roads, it evolved into a highway of its time. This made it a bustling thoroughfare, especially with trips to Haverhill, Londonderry, and Portsmouth. Most stops along the way hosted two trips per week and given the impressive volume of cider being consumed (yes, that's a key historical detail), one can imagine that this tavern was frequented by a considerable number of passengers. Each stage was designed to hold nine passengers plus a driver. If you do the math and consider the possibility of daily stages, that could mean more than 20 visitors passing through the tavern in a single day (with 1-2 stages in each direction daily), not to mention additional patrons of the establishment. Quite the lively hub, I'd say!

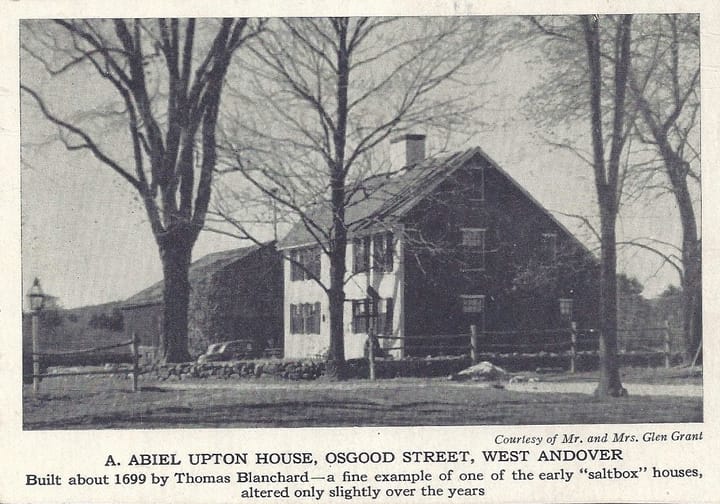

These stage stops were also competition for the existing local taverns. The Isaac Abbot House stands as a testament to changes impacting each tavern. A tavern in the center of Andover from 1776, Abbot’s Tavern served as Andover's first post office from 1795. Isaac Abbot, the innkeeper and postmaster, epitomized the respected citizen: a selectman, town clerk, clerk of the market, and a deacon at the South Church. In 1795, Abbot sold his inn, marking the closure of several establishments in Andover, like: Ballard’s, Blunt’s, Parker’s, Poor’s, and Abbot’s taverns. The Ames tavern, although struggling, persevered into the 19th century. (see A Tavern with Many Names).

Coaches maintained a speed of four or five miles per hour, changing horses every ten miles for efficiency. As the stagecoach arrived, the driver's trumpet announced its presence. Passengers would pause at the tavern to refresh themselves, enjoying a hearty midday meal. Evening brought rest; although private rooms were unheard of, lodgings were provided. Imagine sharing a room with up to eight strangers, each room boasting two to three beds. The tavern owner expected there to be two and sometimes three per bed!

Eastern Stage Company

In 1808, the Eastern Stage Company emerged in New Hampshire, weaving a vast network that blanketed most of New England. Picture this: over 100 horses, numerous skilled drivers, and a bustling system of logistics, blacksmith shops, and post-houses, including Andover’s Jenkins Post House. These stations served the steady stream of passengers journeying in and out of Boston, traversing the picturesque landscapes of eastern Massachusetts.

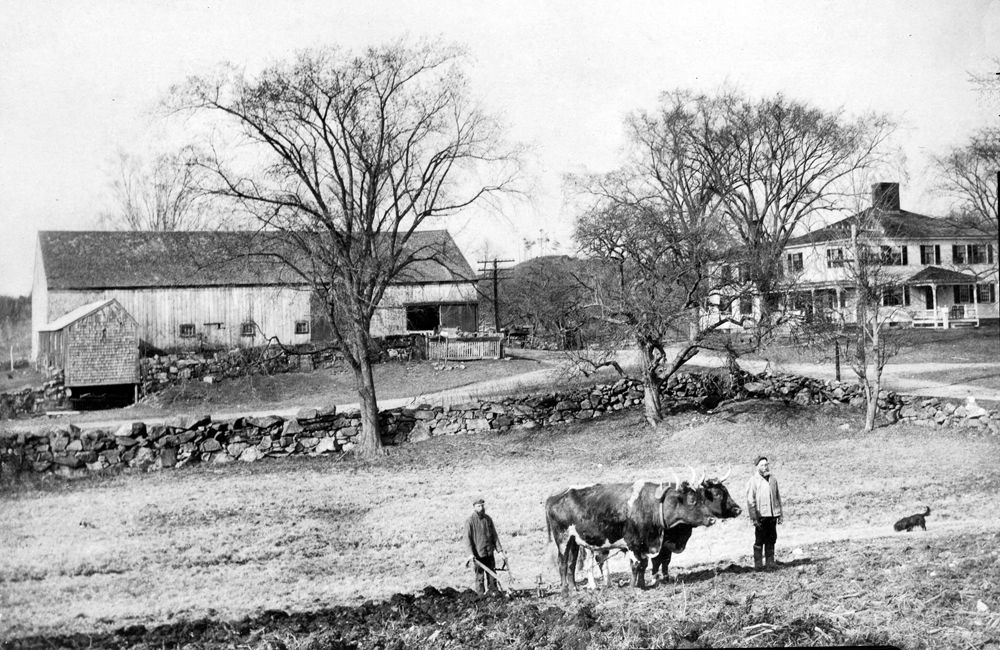

Every stage-coach was pulled by four sturdy horses, each team requiring regular rest, food, and watering. To accommodate this bustling activity, a grand barn stood proudly near the road, a bustling hub of activity. Imagine the scene: multiple coaches arriving daily, each drawn by a fresh team of horses, their hooves clip-clopping on the road.

This barn, a true marvel in its time, stretched over 80 feet and boasted numerous windows, allowing air and sunlight to filter in. It was a bustling place, with teams of horses needing about 1-2 acres of pasture each for their sustenance. The barn with its 15 acres of pasture provided for horses but and various farm animals as well.

Interestingly, the barn was strategically placed right by the road, a stone’s throw away from the passing coaches. Teams of horses could be quickly unhitched, and fresh teams were swiftly brought in to keep the coaches moving at a steady pace. Today, we might find the barn's proximity to the road surprising, but in those vibrant days, it was a hub of activity and life.

In the year 1818, a remarkable venture called the Eastern Stage Company came into being, connecting all the lines in eastern Massachusetts and New Hampshire. This syndicate wasn't just a business; it was a lively thread stitching together communities in Maine and Rhode Island as well. Picture this: in 1829, seventy-seven stage-coach lines emanated from bustling Boston. A journey to Worcester cost a mere two dollars, while the scenic route to Portland required eight dollars.

By 1832, the number of coach lines had surged to one hundred and six, weaving a web of connectivity. But change was on the horizon. The wheels of progress turned swiftly, ushering in rail travel in 1835 and trolleys before that. The stagecoaches, once the heartbeat of travel, found themselves becoming relics of the past.

By 1838, the Eastern Stage Company, once vibrant and bustling, faded into memory. As history unfolded, "The Liberator" newspaper of April 29, 1842, carried news of the Eastern Railroad's multiple trips out of Boston. Imagine the excitement as the Portland-bound rail departed Boston at 10 AM, reaching its destination by 7 PM—a mere nine-hour journey.

The disruptive technologies of stagecoach line and railroad service marked the swift transitions to the end of an era. The iconic taverns of the 17th and 18th centuries and the newer post road taverns, including Andover's Jenkins Post House, succumbed to the inevitable march of progress, making way for the future.

Sources

Andover Historic Preservation Site, many write-ups and photos of Abbot Tavern, Welcome to the Andover Historic Preservation Web Site | Andover Historic Preservation (mhl.org).

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Earle, Alice Morse, Stage-Coach and Tavern Days, The Macmillan Company, London, 1900.

Forbes, Allan and Ralph M. Eastman, Taverns and Stagecoaches of New England, Vol II, State Street Trust Company, Boston, 1954.

Holmes, Oliver W., Stagecoach Travel and Some Aspects of the Staging Business in New England, 1800-1850, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1973, Third Series, Vol. 85 (1973), pp. 36-57, Massachusetts Historical Society, 1973.

Holmes, O.W., The School Boy, poem to celebrate centennial anniversary of Phillips Academy (Andover), in 1878.

Larkin, Jack, Historical Background on Traveling in the Early 19th Century, Old Sturbridge Village Publications, Sturbridge, MA, 2003.

Comments ()