Nurseries of Idleness

“It is notorious, the Number of Taverns, Ale-houses, and Dram-shops, have encreased beyond all Measure or Necessity. They that are placed so near each other, that they ruin one another: and Two Thirds of them are not merely useless, but are become a Pest to Society.” … Many Bills have been presented to the late Governors, to lessen the Number, and to regulate those Nurseries of Idleness and Debauchery, but without success.” Benjamin Franklin, March 1764

Taverns

By 1760, taverns had become ubiquitous across the colonial landscape. Corrupt colonial officials were infamous for profiting from tavern licensing fees, creating a growing number of these establishments. Taverns served as public houses, hosting a myriad of events such as militia drills, private business dealings, and town meetings. These venues mastered the art of maintaining a loyal customer base.

Entertainment, games, and dancing, once strictly prohibited, were now openly embraced within tavern walls. The offerings extended beyond traditional choices like rum, beer, and punch, with innovative cocktails encouraging patrons to indulge freely.

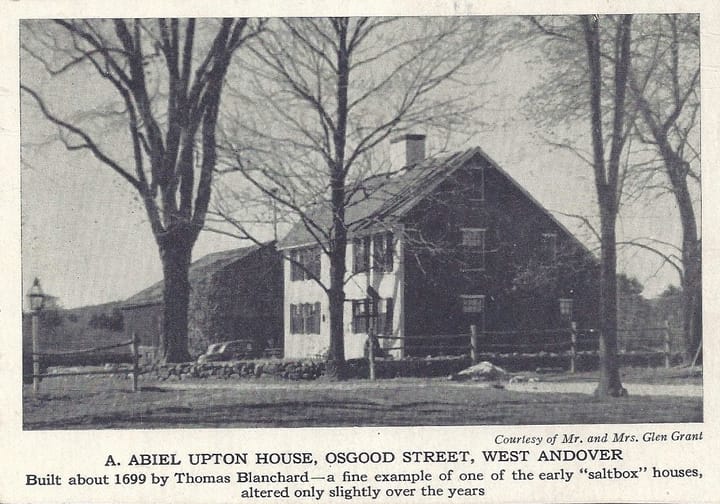

In Andover, MA, the proliferation of taverns was remarkable, reaching at least six for a population of 2,442, translating to roughly one tavern for every 100-150 adult males. This explosion in numbers led to a diverse range of experiences within these establishments. Some were elegant, while others were downright filthy. In Andover, we talked about Ames/Foster’s tavern in a previous blog entry (A Tavern with Many Names) being called a “wretched inn”.

An account from a traveler in Pennsylvania in 1773 vividly captures the stark contrast between these establishments. Describing a country tavern, the traveler lamented, “It was the dirtiest House, without exception in the Province. Every room swarming with Buggs… If I did not pray all Night, I surely watched, as Sleep was entirely banished from my eyes; though I enclosed myself in a Circle of Candle grease, it did not save me from the devourations.”

Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, just like many others, shared concerns about the growing number and nature of taverns during their time. Franklin, in particular, expressed worry about the subpar quality of these establishments and how it affected the local economy and the reputation of taverns in general. He believed that the abundance of taverns made it challenging for the better ones to thrive and be profitable.

On the other hand, John Adams, while openly expressing his concerns about the rowdy behavior commonly found in taverns, understood the need for accessible and reasonably priced liquors for public gatherings. He stressed the significance of having "Liquors in small Quantities and at the cheapest Rates" for such events. Despite his strong stance against excessive drinking, Adams personally indulged in a mug of hard cider, all in the name of his "health."

Conversations of Rebellion

Let's be honest here – taverns weren't the root cause of drunkenness; rum was the culprit. However, it's important to note that rum also played a significant role in the growth of New England's economy. By 1770, the colonies imported a whopping 4 million gallons of rum and distilled another 5 million, mostly New England Rum made in Boston and the nearby areas. Rum was readily available, especially in New England, where it held great importance for the general population.

The increasing number of taverns, coupled with the widespread availability of rum, contributed to a destabilizing influence. These taverns became gathering spots where people could come together, share news, and engage in discussions. Many of the taverns in Andover were also associated with militia members, including the Poor Tavern which informed Salem Poor, a future war hero. It was in these places that many groups found a forum to discuss their war plans, further emphasizing the impact of taverns and alcoholism on the social fabric of the time. (See Salem Poor: Slave to War Hero)

The growing number of taverns hosted conversations of discontent. One European visitor wrote, “Dined in a tavern in a Large Company, the Conversation Continually on the Stamp Dutys. I was really surprised to the people talk so freely, this is common in the country, and much more so to the Northward.”

Sons of Liberty Meetings

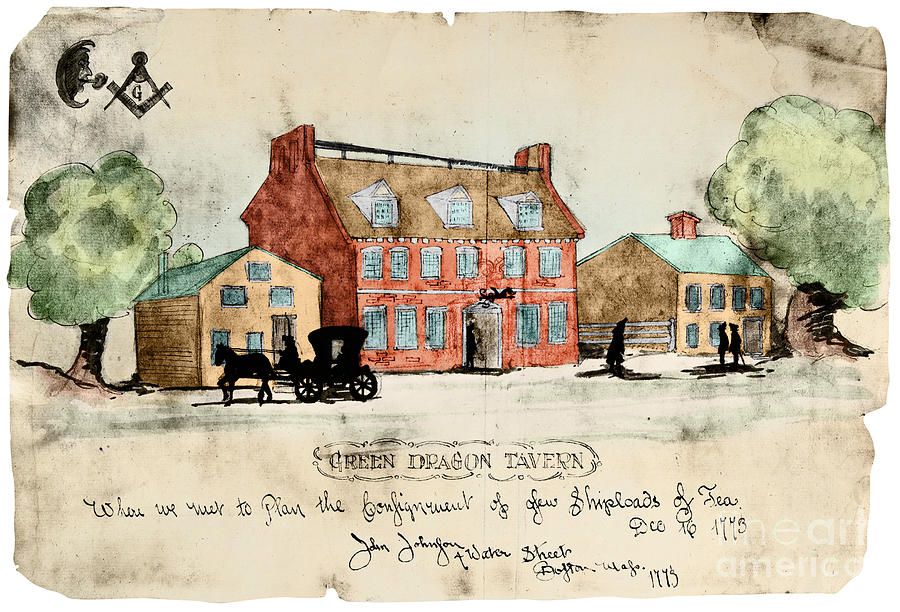

By 1765, the Sons of Liberty had come together to oppose the Stamp Act, led by influential figures like Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Joseph Warren. Their meetings took place in the basement of Boston’s Green Dragon Tavern, owned by the St. Andrew’s Lodge of Freemasons, connecting skilled individuals to the cause of rebellion. This tavern became a focal point for planning acts of defiance, including the renowned Boston Tea Party. (It's worth mentioning that in 1780, Joseph Warren established the Warren Tavern in Charlestown, MA, which still operates today.)

Many tavern owners took pride in hosting local Sons of Liberty gatherings. In York, Maine, one tavern boldly displayed a sign proclaiming, “Entertainment of the Sons of Liberty.” Some taverns set aside space for speakers, with several even featuring Liberty Trees. In Providence, RI, at Olney Tavern, a great elm tree hosted a platform built 20 feet above the ground for speakers to talk about the cause of liberty. The most famous Liberty Tree stood in front of a tavern bearing the same name at the corner of Esses and Washington Street. The tavern was named in celebration of the repeal of the Stamp Act. This Boston Liberty Tree, planted in 1646, was pruned by the Sons of Liberty on February 14, 1766. Unfortunately, British soldiers later cut it down, providing 14 cords of firewood. That was a big tree.

On August 14, 1769, the Liberty Tree was the site of a grand Sons of Liberty assembly. Over 300 people gathered under a tent for a lavish feast, enjoying speeches and songs. After 14 toasts, the attendees headed home. John Adams, in his diary, noted with pride, “to the honor of the Sons I did not see one person intoxicated or near it.” It must have been a delightful night for the tavern owner.

Not every tavern was open to the Sons of Liberty. Take the Earl of Halifax in Portsmouth, NH, for example; it was a gathering place for Loyalists. In 1775, the Sons of Liberty assembled in front of the tavern and took down its sign-post. The owner, in a bid to protect his property, sent his slave, Noble, to confront them. Tragically, Noble was attacked and struck on the head with an axe, enraging the crowd. The tavern was ransacked in the ensuing chaos. Landlord Stavers hurriedly fled the scene, only to find himself in the custody of the Committee of Safety upon his return. Stavers, desperate to resolve his situation, took the oath of allegiance and returned to his tavern, now in a sorry state. The tavern's name was changed to William Pitt, in honor of a friend of America.

However, not every town experienced the mob. In 1768, Andover voiced their disapproval of the violent actions of the Sons of Liberty while supporting resistance against unjust taxation. As September rolled around, King’s troops arrived in Boston, heightening tensions. Andover residents anxiously awaited updates from their representative, Samuel Phillips, a prominent citizen and founder of Phillips Academy, delivered by the post-rider to the town's taverns. Instead of newspapers, taverns became the “daily news.”

Recruits to the Tavern

Militia drills were mandatory for all freemen, held at the tavern chosen by the captain at least eight times a year. By the 1750s, taverns had become crucial recruitment centers during the French and Indian War (1744-1757). These establishments also served as garrison buildings; their sturdy walls designed to withstand attacks. One such attack occurred at Goodman Ayers' tavern in Brookfield, MA, where eighty-two people inside successfully defended themselves against multiple Indian assaults. Despite attempts to set the tavern ablaze, those inside managed to extinguish the flames. Ultimately, a timely rainstorm extinguished the fires, and a group from a neighboring town came to the rescue, driving the Indians away. The tavern's robust walls played a vital role in saving those inside.

“Nurseries of our Legislators”

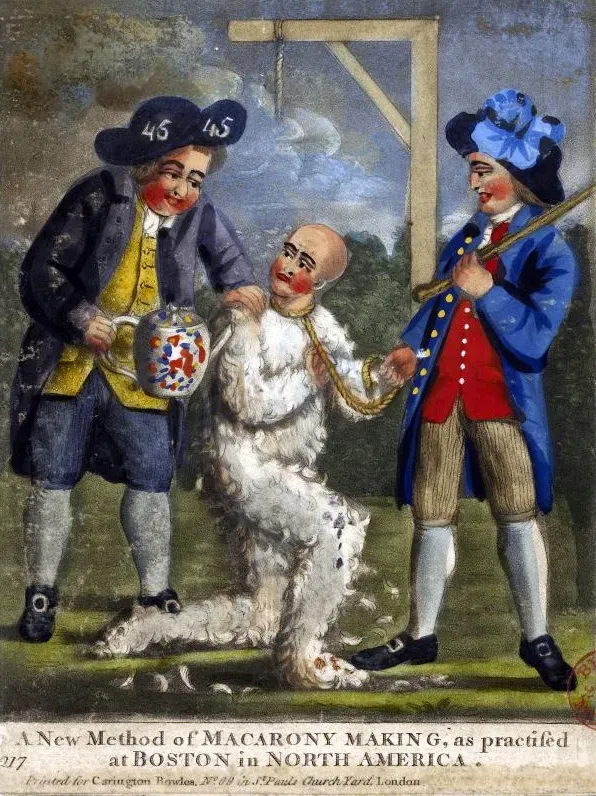

"Nurseries of our Legislators," as John Adams eloquently described them. During the 1760s, taverns played a pivotal role in the rebellion. Initially, John Adams viewed taverns as rowdy places, but with time, he came to recognize their significance as spaces where legislators could truly understand the concerns of the common man. Taverns not only served as hubs for spreading daily news but also as places where people could freely discuss the events of the day over drinks. Militias found recruits and training grounds within these walls. Furthermore, taverns became centers of protest, witnessing incidents like the tarring and feathering of at least 13 individuals (8 in Massachusetts) and the hanging of effigies over Liberty Elms. The Sons of Liberty met in these taverns to plan and execute riots, including the historic Boston Tea Party. What was once a simple place for eating, drinking, and sleeping had transformed into vital hubs where the spirit of Liberty was born and nurtured.

Sources

Andover Center for History and Culture, write-ups and photos of Jenkins Post House, https://www.andoverhistorical.org/.

Andover Historic Preservation Site, write-ups and photos of Abbot Tavern, Welcome to the Andover Historic Preservation Web Site | Andover Historic Preservation (mhl.org).

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Covert, Adrian, Taverns of the American Revolution, Insight Edition, San Rafael, CA.

Earle, Alice Morse, Stage-Coach and Tavern Days, The Macmillan Company, London, 1900.

Comments ()