Street Art: Colonial Style

Tavern signs represent art, politics, and advertising of Colonial America. Explore the history, artists, construction and message of tavern signs as street art of the 18th century

“Our streets are filled with blue boars, black swans, and red lions; not to mention flying pigs, and hogs in armour, with many creatures more extraordinary than any in the deserts of Africa”, says Addison in The Spectator of April 2, 1710. So was the attitude about the many trade signs – beautiful street art that was fun and colorful.

What’s in a Name

Many taverns boast common names like the Black Horse or the Horseshoe from Andover, while others have fascinating stories behind their names. Some are charming corruptions of foreign words; for instance, 'The Pig and Carrot' originated from the French 'Pique et Carreau' (the spade and diamond in playing cards). Another interesting example is the 'Bull and Mouth,' which celebrates the victory of Henry VIII in 'Boulogne Mouth' or Harbor, though the wording got a bit mixed up along the way.

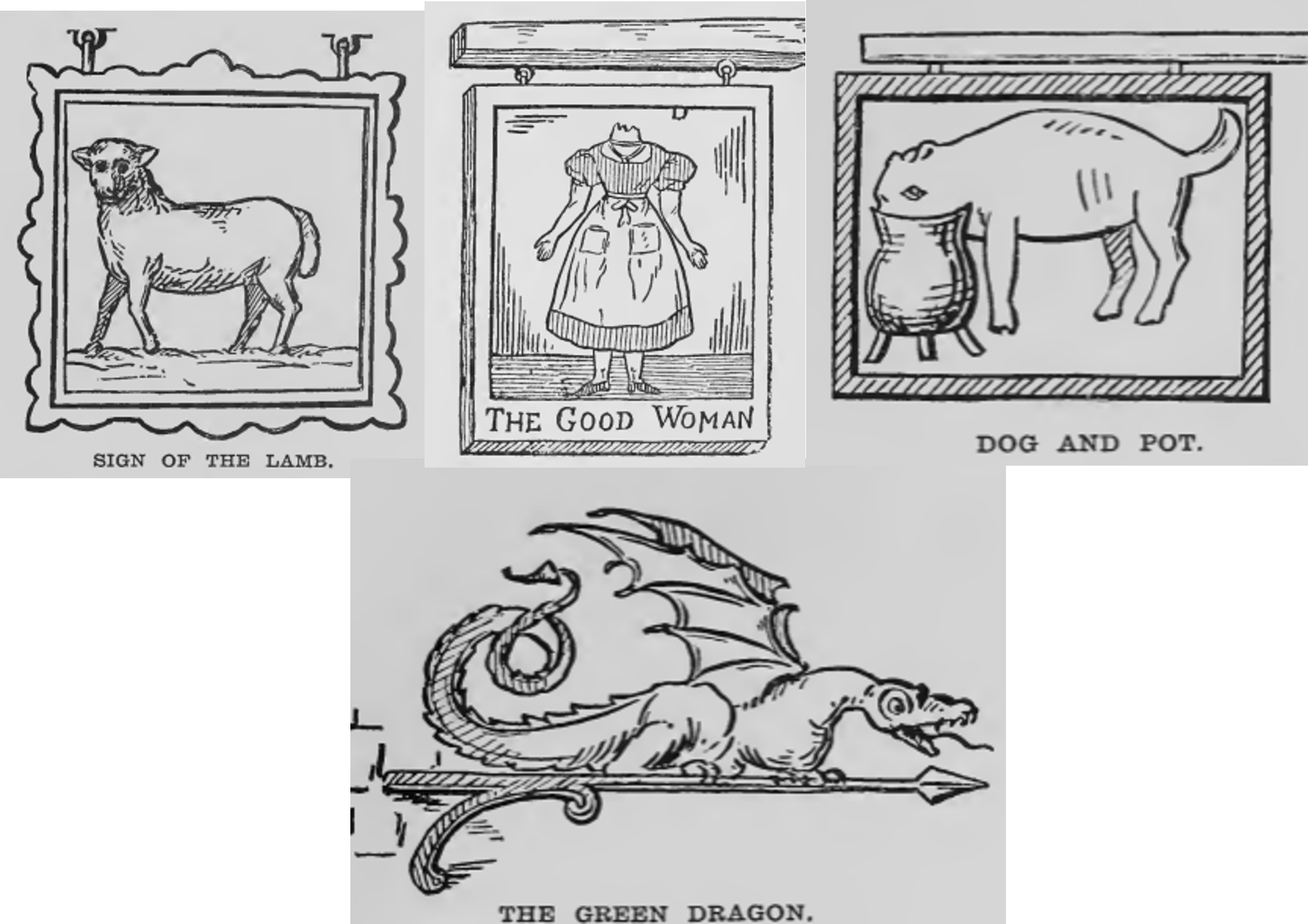

Then there's 'The Good Woman' at the North End, painted without a head, likely making a statement about women not talking much. Personally, I'm a fan of 'Dog and Pot,' a simple yet endearing depiction of a dog licking the bottom of a pot. I'm not entirely sure of its message, but I do love dogs!

Lastly, there's a tavern sign painted with a bird, tree, ship, and a foaming can of beer. While I'm not certain about its deeper meaning, it beautifully connects nature, businesses (shipping), and the joy of drinking, which was a common theme for tavern signs.

“This is the bird that never flew,

This is the tree which never grew,

This is the ship which never sails,

This is the can which never fails.”

Works of Art

Fun names bring along fun signs! Tavern signs, along with other business signs, served as both nameplates and advertisements, often carved or painted on sign boards. Many, especially those from Andover, were simple stenciled signs. Some were the creations of local artists and, while often crudely painted and repainted multiple times, they held a unique charm, despite not being very pretty.

Interestingly, many of these signs were crafted by renowned artists like Gilbert Stuart (famous for his portrait of George Washington), the Peales, Edward Hicks, John Singleton Copley, and Benjamin West. These talented individuals, seeking extra income, turned to creating trade signs, which provided a quick source of money. For instance, West, a celebrated artist from the Philadelphia area and the official painter to King George III, was once offered five hundred dollars for a red lion he had painted for a tavern.

Surprisingly, most tavern signs were unsigned, and many got lost due to exposure to the weather. Edward Hicks, as per his account books, created over three dozen tavern and trade signs, with only six surviving to this day. In contrast, sixty-two of his Peaceable Kingdom paintings have endured. These famous artists, in the early stages of their careers, painted tavern signs as a means of making a living, which is why many of their sign works remain unsigned. Once they were commissioned for portrait paintings, they often transitioned away from painting signs.

Today, these old tavern signs are cherished for their artistic value and have found a place in numerous museums. It's incredible to think about the journey these signs have taken, from the storefronts of bustling taverns to the hallowed halls of art museums.

The Craft of Tavern Signs

Creating signs was a craft that depended on a variety of skilled trades, including woodworking, painting, ornamental metalwork, and sometimes carving. The sign board itself could be made from a single wide board or multiple boards joined together, which often led to future joint cracks. Once the main board was constructed, most signs were set into a structural frame. These frames not only provided stability but also served as decorative elements and attachment points for hanging. With the frame in place, the sign was ready to be painted.

In the early days, signs were typically painted using limited colors, such as white, black, and earth tones. While interior paints and whitewashing techniques were available, exterior paint posed challenges as it wasn't as reliable. It wasn't until the late 18th century that high-quality exterior paint became readily accessible. Consequently, simple paintings had to be repainted regularly to maintain the overall appearance due to the wear and tear caused by changing tastes and the unpredictable weather.

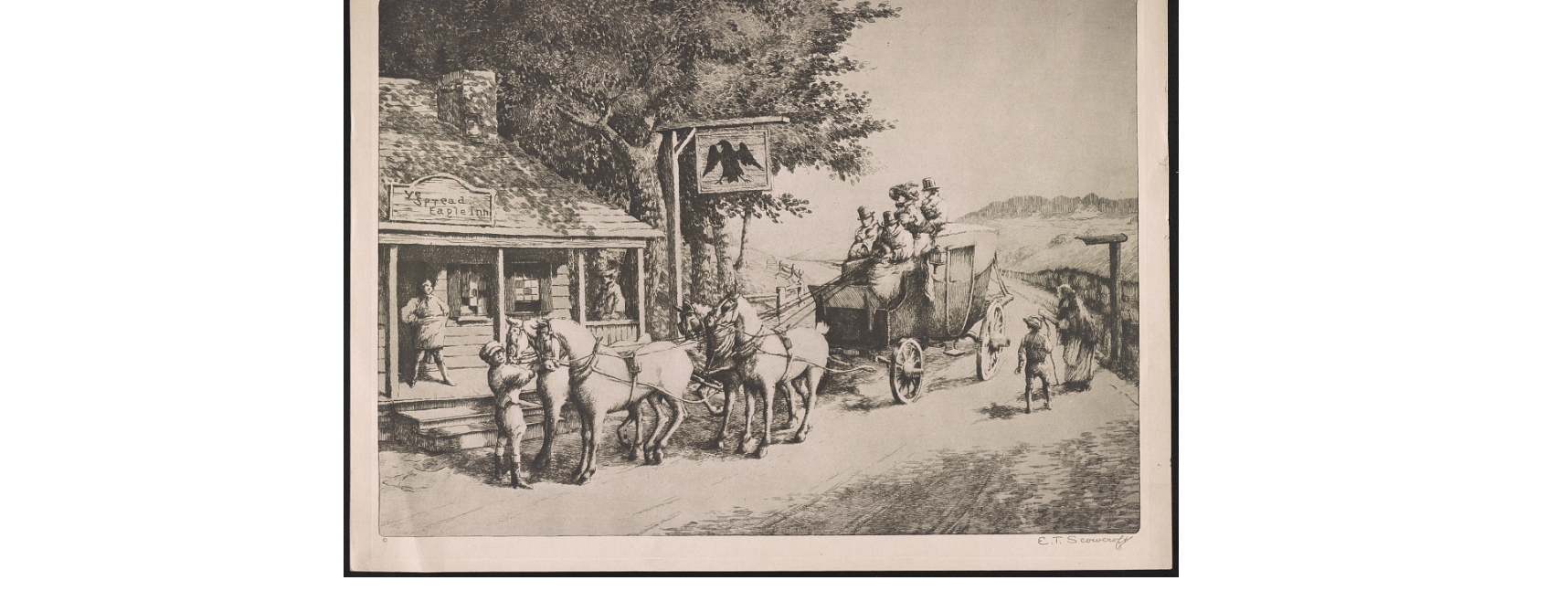

One significant challenge faced by sign-makers was the impact of historical events like the Revolution. Signs that referenced traditions from England and the King, like the Three Crowns, underwent transformations as the Revolution unfolded. Many signs changed to reflect patriotic symbols such as spread eagles or liberty trees. These signs served as a way to welcome passersby, define the type of establishment, and showcase the loyalties of the proprietor.

Take our Black Horse tavern sign, for example; it proudly added the phrase “Entertainment for Sons of Liberty,” making a bold statement about its allegiance and inviting all to enjoy the warm hospitality within.

Ballard’s Tavern Sign

Some families boast a rich history, while others seem to vanish into the depths of time. Take Hezekiah Ballard’s tavern sign, for instance. It's a sizable piece, measuring 37” x 54”, crafted from pine and oak, proudly displaying the silhouette of a black horse. This sign is all that remains of the tavern, offering just a glimpse into the family's past. Unfortunately, much about the tavern, such as its exact location, operational years, and the identities of its patrons, remains shrouded in mystery, making it a truly forgotten tavern.

I'm filled with countless questions, all of which lack answers. For instance, why does the Ballard tavern sign feature a black horse? In earlier times, tavern signs often utilized symbols. The Bell in Hand Tavern, for instance, quite literally displayed a hand holding a bell, while the renowned Green Dragon had a copper dragon that weathered into a shade of green. A sign bearing a black horse would aptly be named the Black Horse Tavern. Today, we refer to it as the Ballard Tavern to identify the tavern's owner. However, during its heyday, it was likely known as the Black Horse Tavern. Considering its establishment in 1771, it's no surprise that the message at the bottom, “Entertainment for Sons of Liberty,” warmly welcomed all Continental soldiers passing by. Andover, with its sympathies aligned with the revolutionary cause, played host to such establishments.

The Ballards of Andover

The Ballards are both famous and obscure. Interestingly, I discover more about the Ballards in other genealogies, like the Chandlers, who owned the notorious Horseshoe tavern from 1686 to 1699. William Ballard, like Thomas and William Chandler, moved to Andover before its incorporation in 1646. He was a husbandman, likely tending to sheep and cattle. One intriguing tidbit we have about Ballard dates back to 1686 when the town, concerned about the frequent destruction caused by roaming animals, designated “a parcel of land lying between ye land of Joseph Ballard, [and others] shall forever lye for a sheep pasture.”

The Ballards were farmers, leading a quiet life in our community, unlike some others who held prominent positions in local offices like selectmen. They were regular patrons of the Horseshoe Tavern, which was owned by William Chandler. In a notable event in 1687, when Chandler faced strong opposition from the Osgood family, owners of a competing tavern in town, Joseph Ballard (William’s son) along with others, signed a petition in support of Chandler's “house of publick entertainment,” ultimately saving the Horseshoe from closure. The Ballards cherished their time at the Horseshoe Tavern, located on the south side of the old town green.

In 1688, William Ballard’s sons, Joseph and John Ballard, championed the establishment of “a grist mill, furring mill, & c.” along the Shawsheen River. The town offered them 20 acres in exchange for setting up the mills. Although it’s unclear whether the Ballards ever set up a furring mill, the town later granted the benefit of the Shawshin stream to Lt. Johns and Ebenezer Baker for erecting a furring mill. The Ballards eventually moved from the old town center to South Parish. This area is now known as Ballardvale, named in honor of the Ballard brothers' first mill district.

Joseph had a son named Hezekiah Ballard in 1682. Hezekiah became a blacksmith, mastering another skilled trade. In 1719, at the age of 37, Hezekiah inherited his father's home. Upon Joseph’s passing in 1751, Hezekiah inherited “all my buildings except the west end for widow,” Rebecca. Following the customs of the time, Rebecca received half of the house along with annual provisions from her son until she remarried or passed away. These provisions included 12 bushels of Indian corn, 10 bushels of rye, 2 bushels of wheat, and cider. Occupying the same building since 1719, the will officially transferred “the part of the ancient homestead that he is now settled upon” along with several lots of land to Hezekiah Jr.

Hezekiah Ballard Jr., our future tavern owner, was born in 1720. He was 31 when he inherited his father’s estate in 1751, already married to Lydia Chandler with a growing family. By 1755, he became a deacon of the South Church, marking his only recorded public service. In 1771, Hezekiah embarked on a new venture, opening the Ballard Tavern, which he operated until 1789 when he eventually sold it.

The Ballards and Chandlers share a rich history that spans the first 150 years of Andover. Both families were involved in various trades, including owning taverns, working as blacksmiths, and running mills (ironworks for the Chandlers and a grist mill for the Ballards). William Chandler's first Horseshoe Tavern was located on what used to be Ballard land. The families were not only neighbors in both the North and South Parishes but also connected through many marriages. They were also part of notable events in our town's history. The Ballards were the first in Andover to accuse someone of being a witch during the Salem Witch Trials of 1692, while William Chandler’s daughter Phebe accused Martha Carrier, one of the unfortunate souls who was executed as a witch.

The Ballard Tavern is gone, only the sign remains.

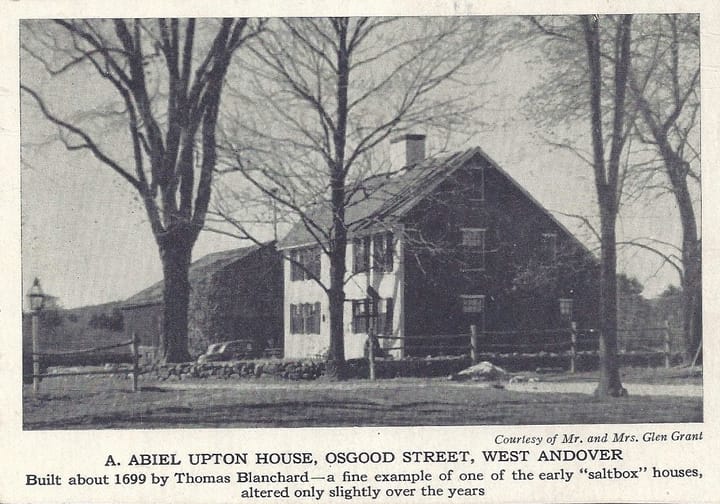

The Ballard Tavern stood near the former location of William Chandler's Horseshoe Tavern only 58 years later. It was situated along the east side of “the road to Boston,” now known as Woburn Street. According to a newspaper article from the 19 C., "The original house on this place stood farther back from the street and had been moved to this location before the time Dea. Ballard came here. The windows in it, with four lights of 9x7 size glass, were situated high up from the ground to offer protection from Indian attacks." Indian attacks in Andover had diminished by the 1690s, suggesting that this house was likely constructed around 1690. Considering the house's location and the timing, one can't help but wonder if this was the old Horseshoe Tavern house, built around 1690 and probably on the adjacent lot.

Today, all that remains of Ballard’s Tavern is the Black Horse Tavern sign, a beautiful reminder of the bustling inn that once welcomed soldiers and travelers along the road to Boston. That charming sign must have been a warm and inviting beacon, promising the coziness and hospitality found inside.

Sources

Abbot, Abiel, A. M. History of Andover: From its Settlement to 1829, Flagg and Gould, Andover, MA, 1829.

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Drake, Samuel Adams, Old Boston Taverns, Cupples, Upham, & Company, Boston, 1886.

Schoelwaer, Susan P. (editor), Lions & Eagles & Bulls: Early American Tavern & Inn Signs from the Connecticut Historical Society, Princeton University Press, 2000.

Comments ()