Taverns: House of Entertainment

As summer comes to an end, so do the outdoor festivals. Summer brings with it parades, holidays like Memorial Day, 4th of July, and Labor Day, lazy days at the beach, and cherished moments on the patio with friends. It's a season that includes sipping a glass of wine, enjoying a cold beer, or even indulging in a "foo-foo" summer drink, all while occasionally quenching our thirst with a glass of water. These are moments we savor in the company of others. Not much has changed in that respect, except perhaps the temperature of the drinks we prefer.

Today, various laws and customs restrict the consumption of alcohol in public spaces. However, in the 17th and 18th centuries, imbibing alcoholic beverages such as beer, cider, or other spirits was as commonplace as drinking water is today. Field laborers would quench their thirst with beer, as illustrated by 12-year-old Phebe Chandler, who delivered beer to her neighbors from her father's tavern, the Horseshoe. During the summer, parishioners attending the morning church session would make their way to the local tavern for lunch and a refreshing drink under a shady tree before returning to church for the afternoon service. Monthly Training Day often took place at the captain's tavern, where beer flowed freely between drills. Having beer was as ordinary as having water in those times.

Taverns actively encouraged drinking by serving up fancy concoctions, offering a valuable public service by providing a gathering place for community meetings, and ensuring entertainment for their patrons. Even in the 17th century, taverns were frequently referred to as Houses of Entertainment, recognizing the community's need for such spaces. In the early days, many games were prohibited, but by the 18th century, card games, dice, bowling, shuffleboard, and darts had become common activities within taverns. As the strict puritanical norms began to relax, dancing gained immense popularity. Dancing also brought music into the mix, often accompanied by singing, including spirited, bawdy songs.

A PLACE FOR CELEBRATIONS

Parades and festivals, including Christmas and Thanksgiving, weren't as widely celebrated in the same way as they are today among the Puritans, who viewed them as just another birthday. Instead, some towns marked these occasions by firing muskets, paying visits to friends, and indulging in hearty meals along with some drinks.

In December 1749, the Masons of Boston gathered at the Royal Exchange Tavern to celebrate the Feast of St. John, and it seems they even had an impromptu procession through the streets.

Guy Fawkes Day on November 5 offered an opportunity for most colonies to discharge their firearms and burn effigies of "Guy." As the Revolution drew near, Boston saw a surge in parades that often started in a tavern, leading to effigy burnings and occasionally causing mishaps. Historical records show how Sam Adams frequented Boston's taverns to sway public opinion.

Not all the beer for these outdoor events came directly from the taverns. There was at least one enterprising citizen who was fined for selling beer without a license, using a handcart to peddle his home-brewed beer during a parade. It sounds quite reminiscent of today's ice cream trucks or fresh lemonade stands at public events. Of course, selling beer still requires a permit today, but back then, having a beer, even if it was served warm, was a common sight wherever people gathered, as it was customary to avoid drinking water.

Weddings were often celebrated at the local tavern, and in the 17th century, they could be quite rowdy affairs, with dancing initially prohibited due to “consequence of some miscarriages at weddings”. However, this prohibition didn't last long, and soon dancing, along with punch and song, became an integral part of these lively celebrations.

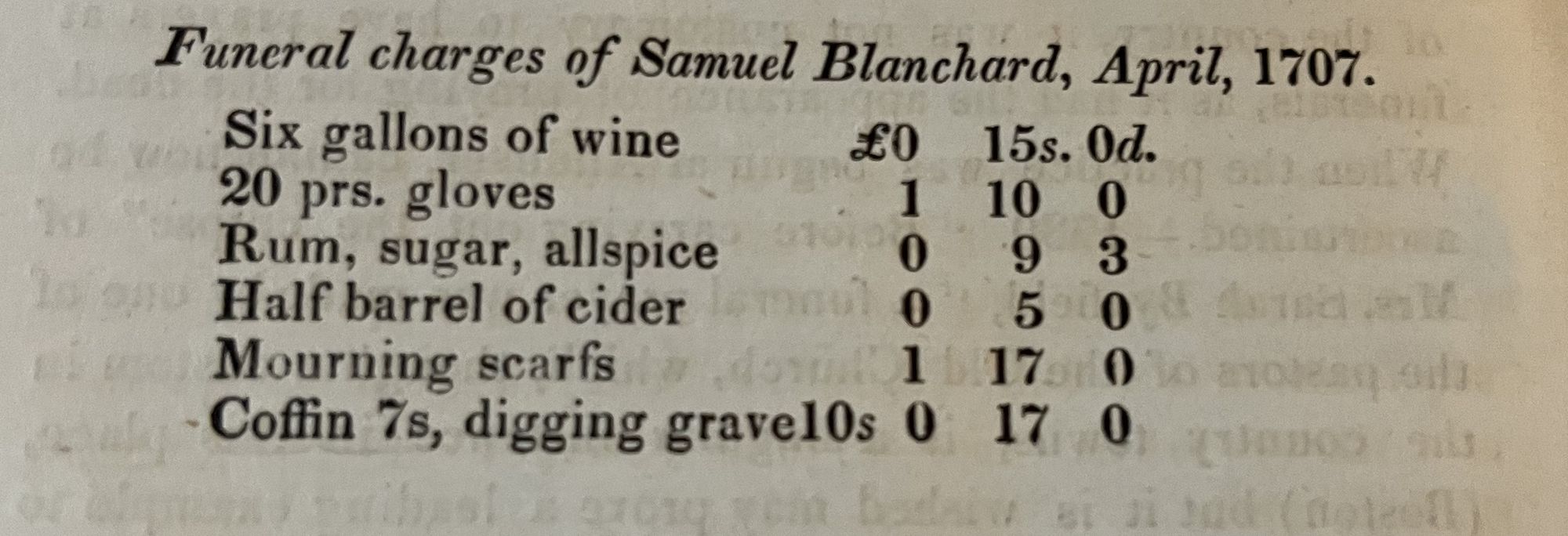

When it came to funerals, it's not entirely clear how many were held at local taverns, but they did serve as a place to gather and drink. For instance, when Samuel Blanchard of Andover, MA passed away in April 1707, his funeral featured six gallons of wine, half a barrel of cider, and a quantity of rum, turning it into a celebration of life.

ENTERTAINMENT

Entertainers had quite a presence in the 1700s, bringing joy and excitement to people's lives with a variety of shows and performances:

Traveling Shows: During this era, traveling shows were all the rage. They featured captivating acts like Punch and Judy shows, waxworks exhibitions, exotic animals such as elephants and camels, and daredevil trapeze artists. An NYC newspaper in 1749 even advertised a waxworks display of the royal family and a puppet show. Similar to today's freak shows, people would gather to witness deformed animals or well-trained pets touring around.

Scientific Shows: Scientific demonstrations were incredibly popular, with a particular fascination for "electrical machines." Professors would journey from tavern to tavern, showcasing innovations like the first lightning rods. In 1755, the Virginia Gazette announced that the Exchange Tavern would host a display of something intriguingly called "the mircosom," designed in the form of a Roman temple (though the specifics remain a mystery). Additionally, hot air balloons took center stage as a spectacular show, often commencing right in front of taverns.

Concerts: In 1735, music enthusiasts were treated to a concert at the Sun Tavern in Boston. Following this, colonial newspapers frequently carried advertisements about upcoming appearances by musicians and singers, reflecting a growing appetite for live musical performances.

Plays: While full-length plays faced resistance in New England, smaller plays known as drolls found a home in taverns. By 1724, audiences were thrilled by a rope dancer and clown named "Pickle Herring" in Philadelphia. However, in 1750, a performance of Otway's Orphans in a Boston residence prompted local magistrates to intervene and shut it down. This opposition led to the rise of historical academies and "moral dialogues" as a popular form of entertainment. These featured small groups of performers sharing their thoughts on various topics, and tickets, priced at six shillings each, often filled the public spaces of larger taverns.

CONTESTS

Sharp-Shooting: Autumn brought with it the excitement of turkey-shooting, and you'd often come across notices announcing these events at the local tavern. For example, one notice from Thos. D Ponsland warmly invited friends and sport enthusiasts to a turkey shoot at Old Baker's Tavern in Upper Parish Beverly on the day after Thanksgiving. The promise was fine, fat turkeys and a good time for all.

Captain Basil Hall, who traveled in America in 1827, was taken aback by one of these turkey-shoots near the Indian river Shawsheen, at a country inn named Andover. He spotted a printed bill at the inn's bar that read: "SPORTSMEN ATTEND, 300 FOWLS will be set up for the sportsmen at the Subscriber’s Hotel in Tewksbury [a neighboring town to Andover], on Friday the 12 October, inst. at 8 A.M." After a chat with the landlord, Captain Hall learned that shooting matches were a common pastime in America. The birds, often just regular barn door fowls, were placed at specific distances (typically around 165 feet) and anyone willing to pay for a shot could take aim. If you managed to hit your mark, you got to take the bird home—a thrilling reward!

Aside from turkey-shooting, other sports like shooting, fox hunts, hunting, and fishing were also quite popular among folks of the time.

Gambling: While gambling was generally frowned upon, lotteries were a common and sanctioned form of entertainment. These "games of chance" were held in nearly every town, usually at a designated tavern. Just as today, churches, colleges, towns, and even states used lotteries to raise funds for various purposes. Many private lotteries drew excited crowds at taverns, offering ticketholders a chance at some excitement and potential winnings.

Horse Racing: Horse racing was a favorite pastime in Boston, and enthusiasts justified it as a means to improve the quality of horse breeds, contributing to the overall sporting spirit of the time.

PUBLIC SERVICE

Training Day and Town Meetings: As we move further into the 18th century, Training Day, which required mandatory attendance eight times a year (once a month), gained increasing significance. It often went hand in hand with Town Meetings, where folks would gather to discuss the pressing issues of the day. Maintaining a well-organized militia was crucial in colonial life, especially given the frequent wars and threats they faced. However, one can't help but wonder how accurate their shooting skills were with all that beer consumption!

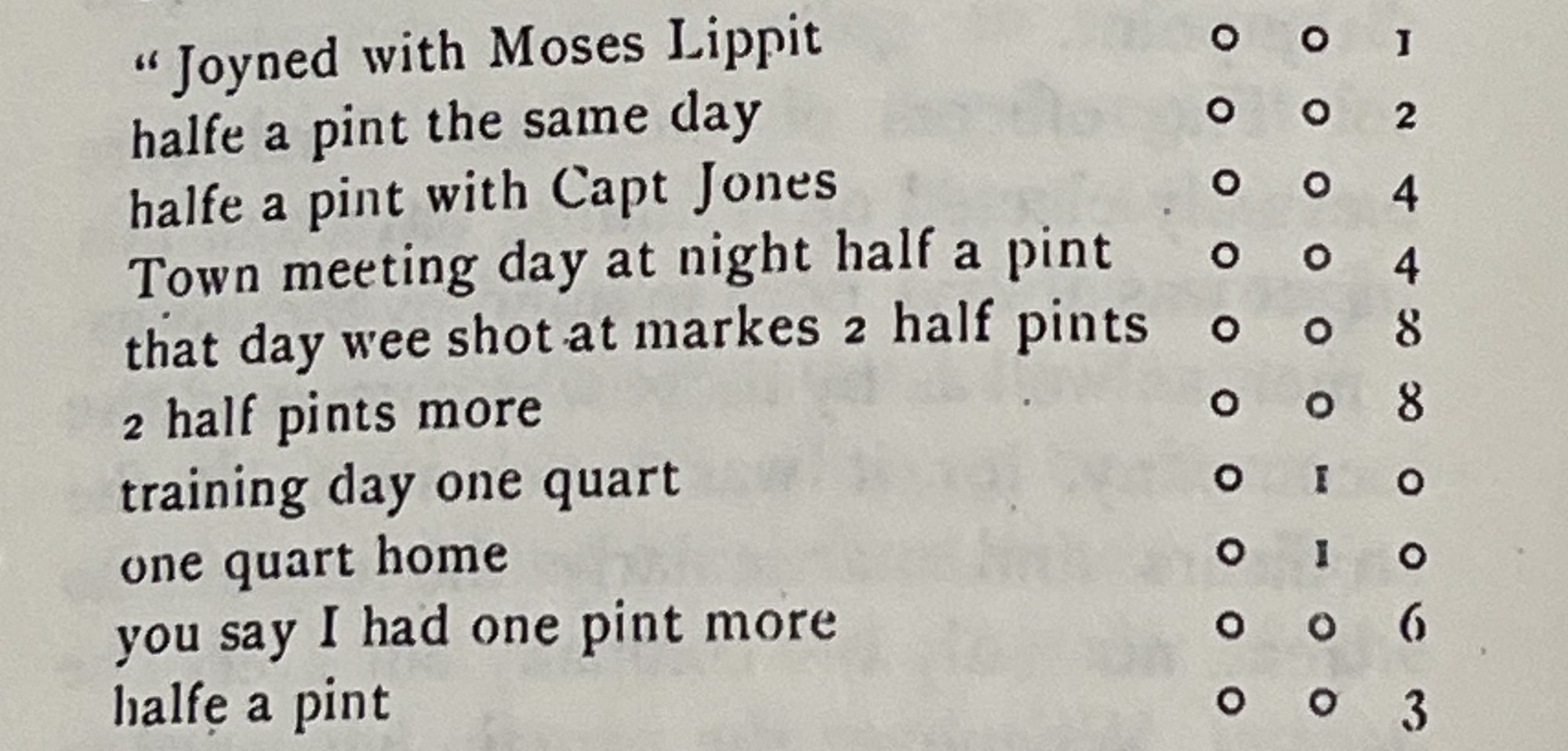

There's a humorous account from a man in Warwick, Rhode Island, who documented his Training Day and Town Meeting experience. He managed to tally over 13 cups of drinks (let's assume it was beer) for that single day. It makes you wonder just how they managed to maintain their focus amidst all that socializing and revelry!

Election or Voting Day: Election Day was the liveliest day in town, and the tavern took center stage. Not only did it serve as the polling place, but it also became a hub for politicians to connect with their voters. George Washington, in his bid for a seat in the Virginia Assembly in 1755, suffered a resounding defeat. However, when he ran again two years later, he had a new strategy. He delivered a whopping 144 gallons of rum, punch, cider, and wine to the polling locations. These beverages were distributed by eager election volunteers who encouraged voters to enjoy a drink or two. With 307 votes, Washington managed to secure almost 2 votes per gallon. It was a time when candidates openly offered intoxication as an incentive to anyone willing to cast a vote for them.

Gathering Places for Meetings: Taverns weren't just for merrymaking; they also played a crucial role as gathering places for various purposes. Small business transactions often unfolded in these taverns, providing a convenient meeting spot for both parties involved. Taverns doubled as courthouses, exchange offices, reading rooms, banks, and sometimes even makeshift jails when needed.

A significant group that often convened in taverns was the Freemasons. Following the English custom, Freemasons held their meetings in these establishments. Frequently, the lodge took its name from the tavern it met in. One Boston lodge met in the Royal Exchange Tavern, hence was known by its name. Some of these gatherings grew so popular that they had to suspend meetings, particularly in the lead-up to the Revolution. Over drinks, individuals like Sam Adams and Paul Revere would come together to discuss the pressing issues of their time.

Going to Meeting: While it may seem odd to have a tavern near the Meetinghouse, it was a legal requirement mandated by the Massachusetts Court. Taverns served as a place for people to have lunch between the morning and afternoon sessions of meetings. Interestingly, many ministers complained about smaller crowds attending the afternoon sessions, possibly due to a little too much indulgence at the taverns.

The British are Coming: As Paul Revere reached Lexington in the early morning hours of April 19, 1775, around 2 AM, he woke up approximately 130 militia men. They gathered and, seeing no immediate threat, headed over to Buckman's Tavern, located across the green. For three hours, they drank and awaited the arrival of British soldiers. It wasn't until around 5 AM that word reached the tavern about the British approaching. The drummer put down his rum and took up his drum, and Captain Parker gathered his men, though by this time, they numbered only about 70. After a night with no sleep and hours of drinking, they were in position.

"They had assembled in a somewhat disorganized, possibly alcohol-affected hurry," as author Philbrick describes it. In the early morning light, Paul Revere and John Lowell, John Hancock's secretary, were seen staggering between the militia and the British, carrying a trunk filled with important, confidential dispatches. It must have been a sight to behold! The identity of the person who fired the first shot, which became known as the "shot heard around the world," remains uncertain. Both sides claimed to have ordered their soldiers to "hold their fire," but after hours of drinking, it's possible that it was the colonists who discharged that first shot. The British Regulars sustained one wounded soldier, while the militia lost eight men and had ten wounded. And so, the Revolutionary War commenced following a night of revelry and drinking.

Today, when we envision a bar, we often think of it as a spot to gather for a drink. However, in colonial times, the tavern was a whole lot more than that. It stood at the heart of town life and served as the ultimate House of Entertainment for everyone in the community.

Sources

Abbot, Abiel, History of Andover from its Settlement to 1829, Flag and Gould, Andover, 1829.

Cheever, Susan, Drinking in America, Our Secret History, Twelve, New York, New York, 2015.

Earle, Alice Morse, Stage Coach and Tavern Days, The MacMillan Company, London, 1900

Field, Edward, The Colonial Tavern, A Glimpse of New England Town Life in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Preston and Rounds, Providence, RI, 1897.

Wright, Louis B., The Culture Life of the American Colonies, 1607-1763, Harper & Brothers, New York, New York, 1957.

Comments ()