The Growth of Whiskey and Temperance

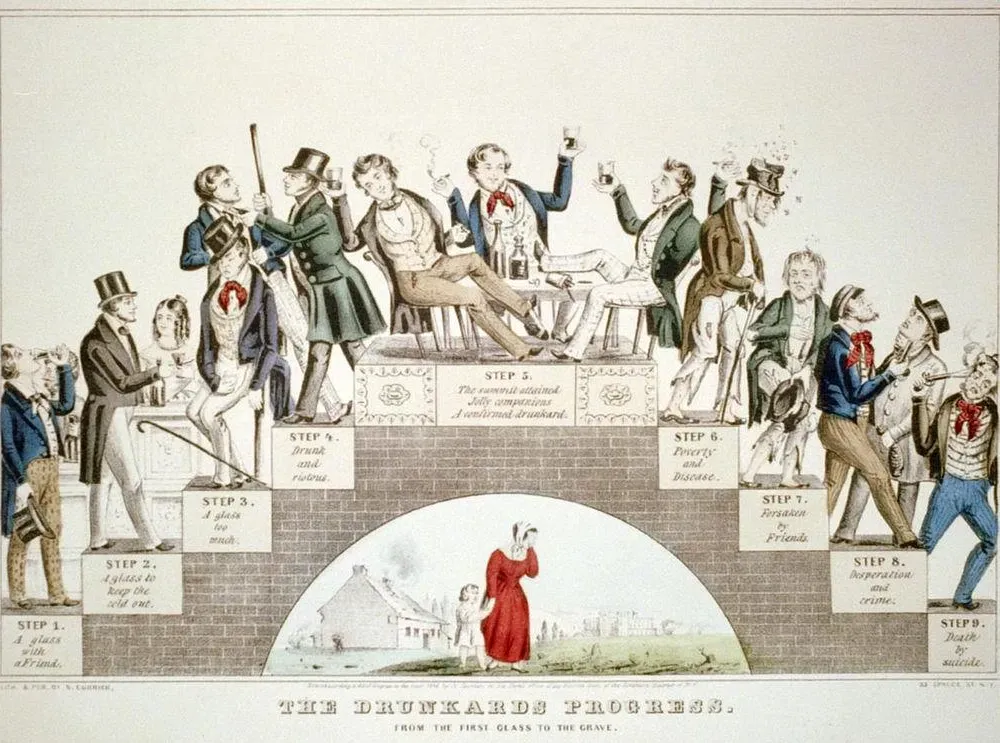

A man who has had too much to drink is in “folly… a calf—in stupidity, an ass – in roaring, a mad bull – in quarrelling and fighting, a dog – in cruelty, a tiger – fetor, a skunk – in filthiness, a hog – in an obscenity, a he -goat", said Dr. Benjamin Rush. Rush's thinking played a major role in shaping the temperance movement, as well as modern ideas about alcoholism.

The Puritans preached about the dangers of excessive drinking, and as early as 1690, Andover grappled with this issue when Mr. Stone killed his wife after a night of heavy drinking, likely at the Horseshoe Tavern. Over the next century, rum replaced beer as the preferred drink in taverns, leading to Boston's dependence on molasses imports and rum production. The influence of alcohol extended into the Revolutionary era, with instances such as a drunken militia at Lexington Green and troops at Valley Forge receiving double rations to endure a harsh winter. On average, males over 15 years old consumed up to seven alcoholic beverages daily.

While it's easy for us to envision idyllic tavern scenes like those from the TV sitcom "Cheers," reality was starkly different, as alcoholism was pervasive. However, like a pendulum, a shift to the opposite extreme was imminent.

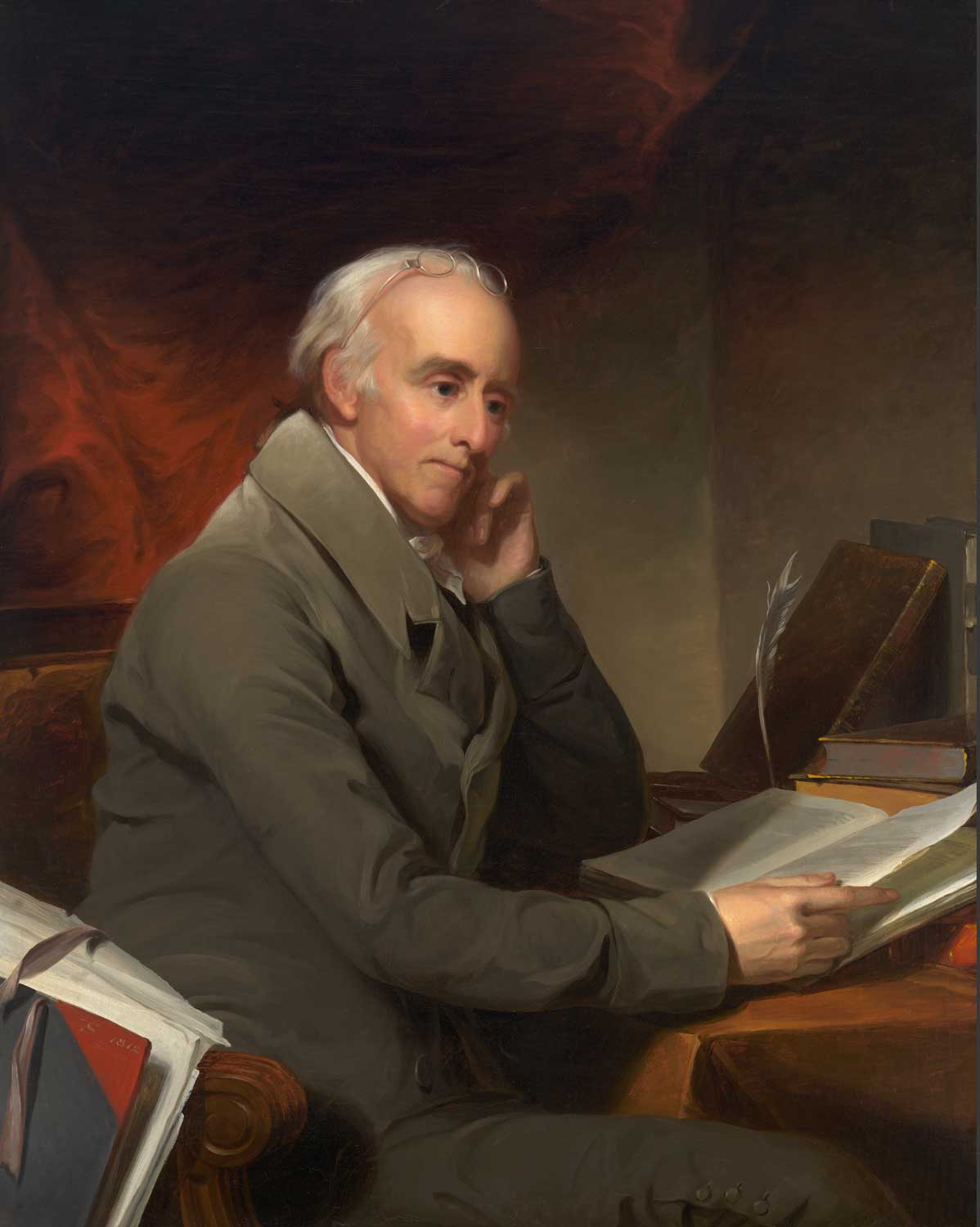

In the late 1700s, Dr. Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia physician and Declaration of Independence signer, developed a keen interest in mental illness, particularly alcoholism. His 1785 publication, "Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon the Human Body and Mind," marked the beginning of the Temperance Movement. Rush viewed alcoholism as a disease rather than a moral failing, attributing the problem to alcohol itself, not the individual. He believed in abstinence as the sole cure and advised alcoholics to "Taste not, handle not." Rush proposed weaning off hard liquor with beer or wine, sometimes incorporating opium. Despite controversial methods like bleeding (Rush bled Benjamin Franklin, and some believe it was what killed Franklin) and emetics of mercury used by other doctors (with George Washington and Louisa May Alcott as examples), Rush's perspective laid the groundwork for understanding alcoholism as a medical condition.

Since the era of the Puritans, colonists held a varied perspective on alcohol, viewing it either as a curse from the devil or a gift from God. Benjamin Rush played a crucial role in reclassifying alcohol as detrimental to those afflicted with the disease.

However, changing these attitudes proved challenging, even among Dr. Rush's friends. For instance, John Adams had personal experience with the impact of alcoholism within his own family, with two sons, two grandsons (from John Quincy Adams), and his brother-in-law, William Smith, all suffering from the affliction. In a letter to Dr. Rush, John Adams writes, “(I am) grieved to heart by the losses sustained because of alcoholism. If I should then in my will, my dying legacy, my posthumous exhortation, … recommend heavy, prohibitory taxes upon spirituous liquors, which I believe to be the only remedy against their deleterious qualities in society, every one of your brother Republican and nine-tenths of the Federalists would say that I was a canting Puritan, a profound hypocrite, setting up standards of morality, frugality, economy, temperance simplicity, and sobriety that I know the age was incapable of.”

Even Adams acknowledged the influence of Puritan teachings about the dangers of drink, showcasing the complexity of challenging ingrained beliefs around alcohol consumption, while experiencing the impacts first-hand.

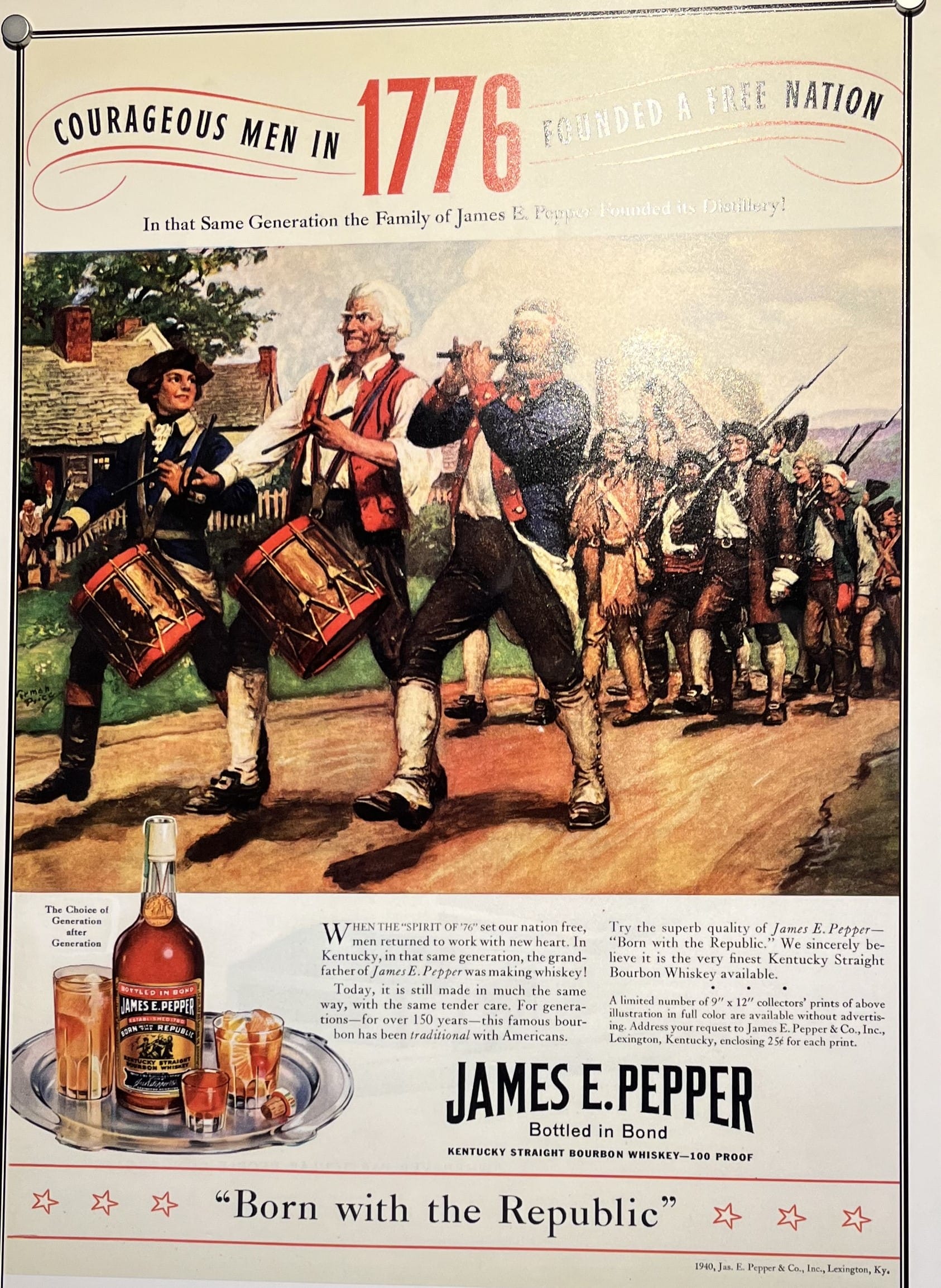

Whiskey comes of age

After the Revolution, the taxes on imports, such as molasses and rum, coupled with the reduced number of distilleries (Boston's count dropped from 38 to 10 post-Revolution), had a notable impact on rum consumption. The shift towards using the fertile lands of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, and elsewhere for locally grown grains made whiskey a profitable and easily transportable alternative, untaxed like rum and molasses. While the roots of whiskey distillation trace back centuries, it became uniquely American, distinguished by the quality of grains, barrels, and blending, setting it apart from Scotch or Irish Whisky.

In 1791, Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury under Washington, proposed a hefty tax on whiskey, molasses, and rum, the latter two already being taxed. Motivated by personal experiences with an alcoholic father who deserted him, Hamilton saw this as a means to generate much-needed revenue while addressing his bias against alcohol. The farming community was incensed; they had just fought to end taxes on rum and molasses, and now they were confronted with a new tax on whiskey. By 1794, Hamilton attempted to bring 75 protesting distillers to court. The situation escalated into violence, prompting Washington to dispatch 15 thousand troops to suppress the uprising in what became known as the Whiskey Rebellion. Two men were found guilty of treason at trial, later pardoned by Washington, indicating his sympathy for their cause but not the rebellion itself.

George Washington, known for enjoying alcohol and the profits tied to its production, operated five stills by 1789, producing eleven thousand gallons of whiskey. His diverse alcohol production included brandy, wine, and beer. In paintings and engravings from this period, Washington is often depicted with a glass of port in hand during social gatherings with friends. Later, during the 1800s, Currier & Ives reworked engravings to remove the glass of port as the Temperance Movement gained momentum.

In 1800, Thomas Jefferson campaigned on the promise to repeal the whiskey tax, recognizing its newfound popularity. However, attitudes were shifting as well, with many Americans feeling the impact of generations of excessive drinking. Taverns, once multifunctional spaces for town meetings, Training Day, and leisure, began to diverge into two distinct types. One retained the old-style tavern atmosphere, with men gathering in the front room for excessive drinks, like the Elm Tavern or the Blunt Tavern. The second type was designed for social events (dances, weddings, etc.) or as an inn, exemplified by Abbot’s Tavern, where Washington visited, or Jenkins Post House for stagecoach travelers. Taverns like the Elm and Blunt faced economic challenges, eventually leading to their closure or sale.

Temperance Movement in Massachusetts

Jenkins Post House epitomized the second category of taverns. Established in 1807, it provided support to the stagecoach travelers, offering meals, beverages, and overnight accommodations. Situated amidst the burgeoning temperance movement in Massachusetts, by 1810, Calvinist ministers were writing articles advocating abstinence, and in 1813, The Massachusetts Society for Suppression of Intemperance was founded.

The Jenkins Post House was notably aligned with the temperance ethos, opting for a limited selection of drinks. After Benjamin Jenkins passed away on February 10, 1821, a probate record revealed a listing of "cider casts worth $12" – a clear departure from rum and whiskey, exclusively offering cider. The Post House was known for hosting dances, especially during the winter when fieldwork subsided. At that time, societal attitudes leaned toward social enjoyment with minimal alcohol. Although the Post House eventually closed due to the decline in stagecoach traffic after Benjamin's death, it mirrors the prevailing sentiments of its era, particularly in Massachusetts.

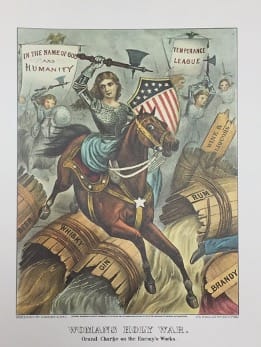

In 1826, the American Society for the Promotion of Temperance was established in Boston. Shortly afterward, the American Temperance Society (ATS) formed, boasting 2,220 local chapters in the U.S. within five years, with 170,000 members pledging abstinence from distilled beverages, excluding wine and beer. ATS advocated for the prohibition of alcohol, initiating a national conversation about drinking habits. While the immediate impact on temperance was limited until after 1830, it sparked changes in societal norms. Employers ceased providing time for drinking breaks, rum jugs for field workers disappeared, and even the military stopped rationing drinks. This period marked the decline of taverns' heyday, with successful ones evolving into men's clubs or inns.

Attitudes in New England shifted, led by abolitionists and increasingly by women in the Temperance Movement. The rising issue of alcoholism, coupled with temperance advocacy, prompted legislators to enact stricter rules. In 1838, activists in Massachusetts pushed for a temperance law prohibiting the sale of spirits in quantities less than 15 gallons. In 1851, Maine became the first state to adopt a prohibition law, with exceptions for "medicinal, mechanical, and manufacturing purposes." Notably, Maine's early adoption of temperance laws reflected the strong historical and family ties with Massachusetts.

Massachusetts enacted its own prohibition law in 1852, yet by 1853, a staggering 60 million gallons of spirits were consumed in America for a population of over 23 million, equating to 15 bottles of alcohol per person. By 1855, Massachusetts passed laws to protect spouses and other individuals from abuse by alcoholics. However, the winter of 1867 saw a petition with over 30,000 signatures presented to the Legislature against state-wide prohibition. This led to a repeal in 1868 and the implementation of a new liquor law regulating the sale of alcohol, including beer and cider, on the "Lord's Day," and specifying where, how much, and when alcohol could be sold. Prohibition in Massachusetts was reinstated in 1869 but repealed again in 1875. The state would not face prohibition again until the 18th Amendment was passed on January 16, 1919.

Maine and Massachusetts were quickly joined by the ranks of Minnesota, Rhode Island, Vermont, Michigan, Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, and New York. By the time the 18th Amendment was proposed in December of 1917, all the original states had abandoned prohibition, but an additional 26 states had embraced the dry movement. The intricate history of temperance and prohibition spans a much longer period than many may realize.

The Puritan influence remains ingrained in Massachusetts culture and behavior, persisting for nearly 400 years. I often playfully refer to Massachusetts as one of the most liberal yet conservative states in the Union. Certain aspects, like liquor laws, tend to lean towards the conservative side and are generally accepted without much discussion. I can recall growing up in Massachusetts with strict alcohol regulations and the presence of "blue laws" that limited liquor purchases on Sundays. It wasn't until the onset of Covid that these laws saw some relaxation, though they remain more stringent than in many other states. For instance, you still can't purchase any alcohol in a grocery store, not even wine. The complexities of our state's history with temperance and alcohol regulations are indeed fascinating.

Nostalgia vs. Reality

Taverns bore the brunt of the Temperance Movement and Prohibition Laws, coupled with the impacts of emerging transportation modes, as we've discussed before. Even in today's world, where many restaurants and bars derive a significant portion of their profit from alcoholic beverages, it's not surprising that taverns struggled to withstand the blow to their alcohol sales. In Andover, all the old-style taverns with a single-room bar in the front closed down, and by the mid-century, only three remained. These surviving establishments adapted by offering overnight accommodations and serving as meeting places for men.

Nowadays, when we visit historic taverns like the Pitt Tavern at Strawbery Banke, we're treated to a carefully recreated atmosphere with intimate seating and a warm fire. However, what these reenactments often miss are the sounds and scenes of men overindulging, lacking a true understanding of alcoholism, and the unsightly consequences of excessive drinking. By the 1830s, the golden era of old taverns had faded, and the pendulum was swinging toward Prohibition.

I confess to enjoying the nostalgic portrayal of the old tavern, where the warmth of the fire accompanies a pleasant drink. However, this romanticized view likely obscures the reality of our past—a past marred by overindulgence and the harsh realities of too much alcohol.

Sources

Cheever, Susan, Drinking in America, Our Secret History, Twelve, New York, 2015.

Clark, Rev. Rufus W., Fifty Arguments in favor of sustaining and enforcing the Massachusetts Anti-Liquor Law, John Jewett and Company, Boston, 1853.

Curtis, Joseph Henry, Prohibition was a failure in Massachusetts in 1867. Is History about to repeat itself in 1922?, Boston, 1922.

Grasse, Steven, Colonial Spirits, A Toast to Our Drunken History, Abrams Image, New York, 2016.

The Libertarian Newspaper, March 30, 1855, article reporting on new laws to protect women.

Comments ()