The Wine Triangle

Last week, I had the wonderful opportunity to visit Tenerife in the Canary Islands and delve into its rich wine history. I'm excited to share what I learned in this episode, and I want to extend a special thanks to Bodegas Monje for their incredible hospitality.

During my visit, I discovered fascinating insights into the wine trade between the Canary Islands and the Americas, as well as the significant impact of government intervention on the local wine industry. It's reminiscent of how England regulated the rum industry in the American colonies. But before I get ahead of myself, let me tell you more about the Canary Islands.

The Canary Islands

Situated 62 miles off the coast of Northern Africa, the Canary Islands form a Spanish autonomous community. In the 14th century, explorers from Portugal, Mallorca, and Genoa frequently visited these islands. By the early 15th century, the Castilians had conquered the Canaries, with major conquests occurring on Gran Canaria (1483), La Palma (1493), and Tenerife (1496). This marked a transformative period for the islands, as they shifted towards a monoculture focused on exporting sugar. This agricultural practice, much like that of Barbados, involved the use of slaves, albeit for a shorter duration.

The grape vines introduced by the conquerors flourished in the islands' favorable climate and soil. Described as dry, light, stony, sandy, and rich in volcanic lava, the land boasted hills and slopes ideal for vine cultivation. In 1513, Andrés Bernáldez eloquently described the land as "very virtuous, suitable for growing vines, trees, and all plants." Each settler dedicated their estate to vine cultivation, alongside other crops, for both personal consumption and the market.

During the early years of the 15th century, local wine production struggled to meet demand, leading to the importation of wines from Seville and Madeira. To address this, imports were regulated, which in turn spurred an increase in local production. Then, in 1520, La Palma implemented a ban on imports, further boosting internal supply. Within a short span of time, the islands of La Palma and Tenerife began exporting their wines, marking the beginning of their international trade.

The Canary Islands quickly transformed from a region with few vineyards to a major exporter of wines to the Indies, England, and Portugal, including their colonial territories. Between 1520 and 1550, wine production saw a significant surge, with the Indies emerging as the primary foreign market. By 1640, annual cultivation volume had reached ten thousand hectares, firmly establishing the islands in foreign markets.

Shakespeare, the marketeer

England had a fondness for Canarian wine, and Shakespeare himself immortalized it in several of his plays, including Henry IV (1600), Twelfth Night (1602), and The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602). In Henry IV, he humorously remarks, "but yfaith you have drunk too much cannaries, and that’s a marvelous searching wine, and it perfumes the blood.”

During Shakespeare's time, many writers made reference to Canary wine, which only added to its allure in England. It's unclear whether England's love for Canary wine existed before Shakespeare's writings or if his works influenced its popularity. Perhaps it was a bit of both?

Although England had a tradition of importing wines from the Eastern Mediterranean, the instability caused by Ottoman imperialism prompted a search for new sources of supply, leading to increased reliance on the Canary Islands and Madeira. Malvasía was highly valued both for drinking and medicinal purposes, being used in the preparation of laudanum and to combat ailments like gout and diabetes.

The Malvasía grape, originally from the Mediterranean, thrived in the Canary Islands' climatic and volcanic soil conditions. Soon, it became the primary export to foreign markets, especially England, where it was known as Canary or Sherry sack.

Historians like Rumeu de Armas noted the intense consumption of Canarian wine in England during the 16th century, suggesting that almost 85% of Tenerife's production destined for the English ports. Production and exports continued to rise until the late 17th century.

Sack

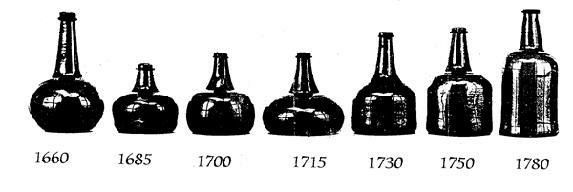

The term "sack" was a generic name for various types of fortified wines, including Canary Sack, Sherry Sack, Palm Sack, or Malaga Sack, which were imported from Spain and the Canary Islands. The wine that was sometimes sold in taverns as Canary wine was a mixture of other Spanish wines. Sack was typically a strong, sweet, and often golden-colored wine, similar to modern-day sherry. Sack was made by fortifying wine with additional alcohol, usually brandy, during the fermentation process.

During the early 1600s, there was a notable increase in the consumption of alcoholic beverages. Wine was considered a product of the wealthy compared to beer, which was more popular. Lawyers, politicians, and businessmen literally gathered in the local tavern or ordinary to drink, sing, and discuss various current topics. Drinking songs were popular, often accompanied by sack or canary.

Trade

The Canary Islands faced their own challenges. In 1640, Portugal gained independence from the Spanish crown, prompting Charles II of England to restrict foreign ships in their colonies. Acts like the Navigation Act (1651), Navigation Laws (1660-1661), and Staple Act (1663) mandated that all goods shipped to England originate from an English port. Madeira, being Portuguese, avoided these restrictions, posing increased competition for wine sales. However, many merchants saw an opportunity to introduce Canarian wine at a lower price compared to Portuguese wine, and also benefit from the return voyage in Caribbean ports like Barbados, a British colony.

During this period, Barbados flourished with a booming sugar and molasses trade, estimating a population of up to 100,000. It's ironic that Barbados served as a port for trading Canary wine, considering that just a century later, it would petition Parliament to enact the Molasses and Sugar Acts to combat trade diversion to places like Martinique, citing "pirates" from the Colonies bypassing Barbados. Similarly, the Canary Islands seemed to be seeking the same workaround, circumventing Parliament's rules to trade in Barbados.

Although the English Navigation Acts prohibited direct trade with its ports, the American Colonies emerged as an alternative option. Portuguese (Madeira) wines could not satisfy the high demand, so the Canaries created a “fake Madeira” at a cheaper price. Vidueño wine was blended with red wines and spirits to resemble Madeiran wine. This trade with the Colonies flourished. Boston, along with the ports of Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore, became key destinations. The profitability of this trade business, along with the cooperation of colonial officials and merchant strategies, relied heavily on the return voyage, primarily carrying flour, which ended up in Caribbean ports, as the demand in the Canary Islands couldn't absorb American products like lumber.

Colonists drink sack

Canary Sack, much like in London, was a favorite in many American taverns, especially among the upper class. George Washington was known to be a fan of canary wine and even used it for medicinal purposes. In 1757, Washington wrote to a friend, Sarah Fairfax, about his need for Canary Wine. He expressed, “Dear Madam, I have been feeling unwell for more than three months now and, since I have not found relief on this site, but rather have felt worse, I have decided to follow my doctor's advice …… I also wanted to ask you the favor of lending me a pound (or, if you can't afford it, less) of green tea. … Also please lend me a bottle or two of Mountain wine or Canary Wine.”

While in Tenerife, I heard that the signers of the Declaration of Independence celebrated the event with a glass of Canary Wine. While this is entirely believable, I haven't been able to find a reference to confirm it. However, I do know that Washington hosted wine parties, including one with over 30 bottles of Madeira. Members of the Continental Congress often frequented local taverns for a drink after a day of work. Gentlemen preferred wine over rum and beer, so a toast with Canary Wine is likely.

Between the end of the 18th century and the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars (1814), Canarian wine only found accommodation in American ports. The powdery mildew plague of 1852 marked a historical break and the end of a cycle, although it was spared another pest, phylloxera. Phylloxera, an aphid-like insect that attacks the roots and leaves of grapevines. Phylloxera devastated vineyards across Europe and other parts of the world in the late 19th century. However, it did not affect the Canary Islands because the insect is unable to survive in the island's volcanic soils. Therefore, the Canary Islands were one of the few regions in the world unaffected by the phylloxera epidemic. As a result, some of the oldest grape varieties in the world exist in the Canary Islands.

One more American tie

The Canary Islands are the origin of the vines planted in the Americas. Franciscan missionaries propagated “mission grapes” in Peru, Argentina, Chile, and California, according to historical research and genetics, with their precedent in the Listán variety prieto, still present in the island vineyards. I was fortunate to see 200-year-old vines while on the island.

Conclusion

It never ceases to amaze me how much international trade was happening from the 16th to the 18th centuries, especially when it came to alcohol. If you're anything like me, you might have imagined our colonial ancestors as completely self-sufficient, making everything they needed right at home. But the reality was quite different. International trade was essential for obtaining goods that simply couldn't be produced locally, like fine wine. While wine was certainly made at home, it's hard to imagine matching the quality of Canary Sack after witnessing the volcanic soil and hills of Tenerife.

It's also fascinating to see how common it was for people to explore new markets or create cheaper products to attract buyers. The Canaries, for instance, came up with a budget-friendly version of Madeira, while Boston produced a low-cost rum known as New England Rum. Both strategies pushed the boundaries of regulations, competed fiercely, and aimed to avoid taxes while maintaining a balanced trade. The Wine Trade Triangle provided Boston merchants, with a source of funding that wasn't available from England and offered a market for Canary Island wines.

I would like to thank my new friends in Tenerife for a wonderful visit. I hope you continue to make great wines for years to come.

Sources

Bodegas Monje, El Sauzal, Tenerife, Canary Islands, website: https://bodegasmonje.com/en/about-us/

Cheever, Susan, Drinking in America, Our Secret History, Twelve, New York, New York, 2015.

Siverio, Juan Jesus Mendez, El vino que perfuma la sangre, Calle La Palmita, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands, 2022.

Comments ()