17th C Rum, Trade, and Infrastructure

It's truly fascinating to think about the extent of international trade that occurred during the 17th century, even in a town like Andover. This frontier town rapidly emerged as a thriving hub of trade with the West Indies. However, along with this trade and growth, there was an unintended consequence—a rising issue of alcohol consumption, primarily due to the higher alcohol content of rum compared to other popular drinks of that era, such as cider and beer. But let's not jump ahead in the story just yet.

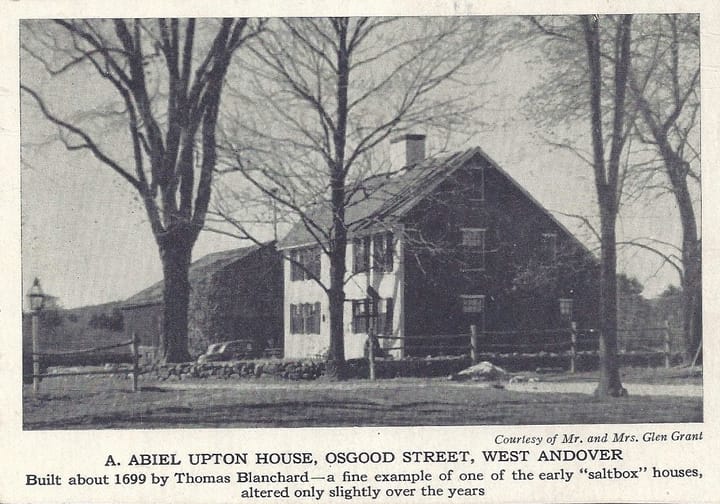

In 1644, most trade, especially lumber, flowed towards the coast along the Merrimack River. Simon Bradstreet, one of the founding fathers of Andover and a future Governor, had a sawmill commissioned on the Cochichewick River. It is believed that the sawmill became operational around 1644 (in 1646, Bradstreet purchased a half interest in a sawmill in Reading). The Cochichewick River was an ideal location for a mill because its water speed was consistent and slow enough for an old-style mill. However, it is unlikely that Bradstreet himself built or operated the mill, as it required a skilled tradesman, and Bradstreet belonged to the gentry. It is more likely that he employed a millwright, such as Joseph Parker (who had a mill later on), to construct his mill.

Bradstreet crossed the Atlantic with the Winthrop fleet in 1629 and settled in Ipswich, where he lived next to the minister and was addressed as "Mister." Being from Lincolnshire, England, Bradstreet was a gentleman who received the largest original house lot of 20 acres once he moved to Andover. He actively participated in the community and saw a business opportunity in this new frontier. Providing lumber for new construction in Andover, throughout Essex County, and for export trade proved to be a lucrative business. The sawmill was constantly busy with construction activities, followed by the trade of lumber to Barbados.

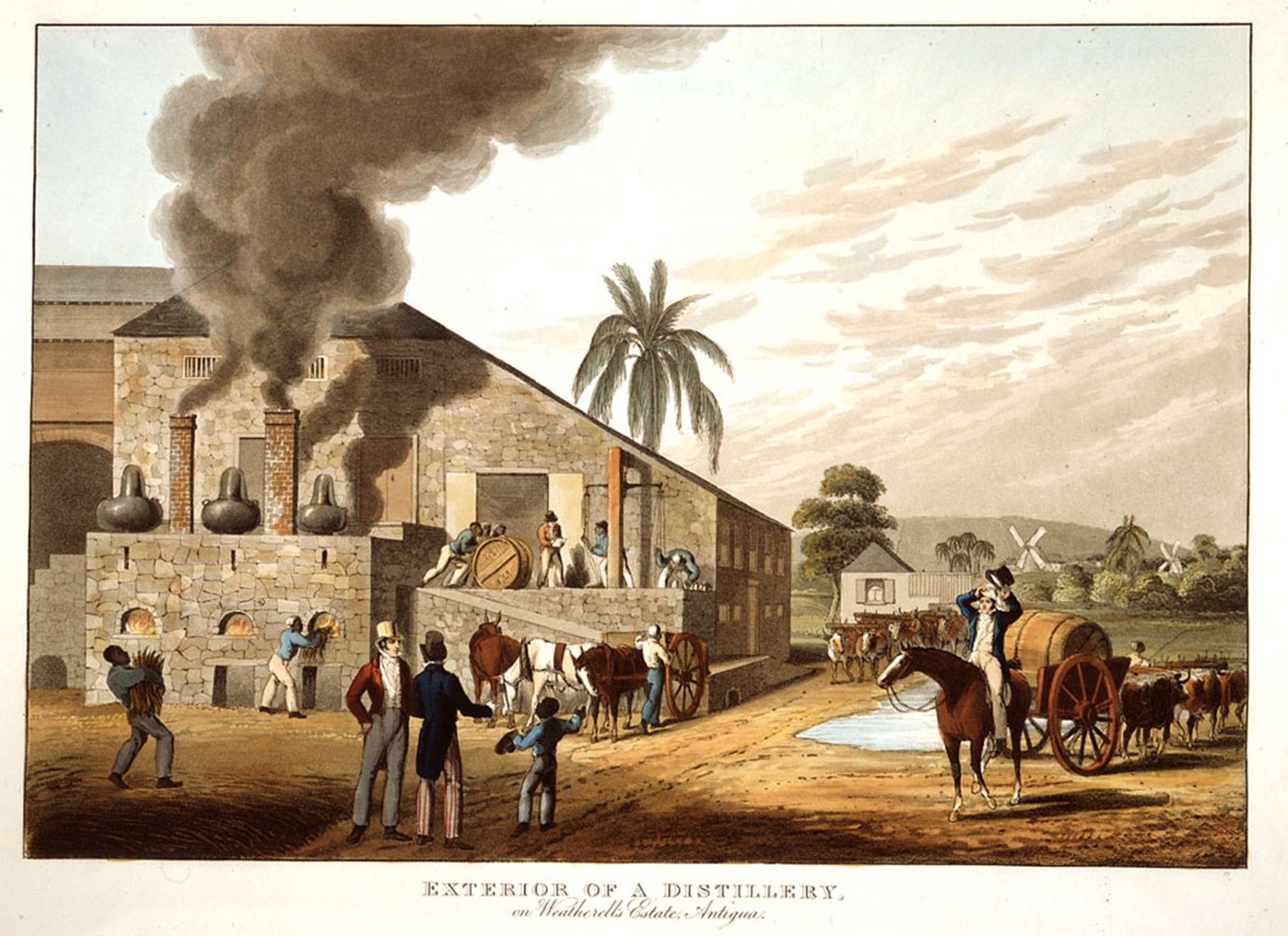

Starting from the 1640s, trading between New England and the West Indies, particularly the profitable trade of cod, lumber products, and livestock, especially horses needed for hauling sugar cane, became prevalent. Andover, with its vast forests and access to the ocean through the Merrimack River, was well positioned to take advantage of this opportunity. Barbados, the fastest-growing colony in the hemisphere, had a significant demand for lumber to support the growth of sugar and molasses, subsequently leading to rum production. Bradstreet recognized this connection, and Andover became involved in international trade.

The exact origins of rum are still debated, with various accounts pointing to Cuba, the east coast of Brazil, or Barbados. However, what we do know is that by the mid-17th century, rum production had expanded rapidly across multiple sites. Although the first documented evidence is scarce, in September 1639, British sea captain John Josselyn mentioned a dinner off the coast of present-day Maine, during which he was toasted by another captain with a pint of rum.

The growth of Barbados

Between 1660 and 1700, the consumption of sugar per person in Britain increased fourfold. This tremendous growth in sugar consumption turned Barbados into one of the wealthiest places in the world by the mid-1600s. Despite being a small island, measuring only 14 miles wide by 21 miles long, Barbados experienced a remarkable population growth, rising from 80 inhabitants in 1627 to 75,000 by 1650. The production of sugar and rum became significant industries, especially as sugar was used to sweeten new beverages such as coffee (which arrived in Britain in 1650), chocolate (1657), and tea (1660).

Rum is produced from the byproduct of sugar production, namely molasses. As sugar crystallizes in clay pots, a dark syrup known as molasses flows out from the bottom. Approximately one pound of molasses is produced from every two to three pounds of sugar. Initially, molasses served as feed for livestock, fertilizer, or was disposed of in various ways, including being dumped into the ocean. However, as the production of sugar increased, so did the amount of waste. This prompted the search for alternative uses, leading to the discovery of rum. Molasses still contained some sugar residue, sufficient for yeast to ferment and subsequently be distilled into rum.

In his book "The Wealth of Nations" (1776), Adam Smith wrote that sugar planters expected that the profits from rum and molasses would cover the entire cost of sugar cultivation. The substantial sales of sugar were almost entirely profit. Many sugar producers considered rum as a means of offsetting expenses. This new profit model encouraged investments in better distillation equipment and led to the production of higher quality rum. Rum also served as a form of currency. Although a Massachusetts law in 1645 prohibited payment of workers with alcoholic beverages, it seems that this rule was not strictly enforced.

The earliest records indicate that Barbados began producing rum around 1652, and by 1655, the island was producing 900,000 gallons of rum, also known as "Kill-devil," annually. However, very few exports were officially reported. Smuggling of rum to England and other colonies was prevalent. In Andover's records, there is an account of John Stevens being charged with intoxication after drinking Kill Devil in 1658. Even by 1665, molasses accounted for less than 1 percent of Barbados' exports, with the majority being rum.

During this period, the West Indies expanded their sugar plantations and had a high demand for lumber, horses, and cod. Barbados, as an English colony, emerged as the largest producer of sugar and molasses in the West Indies.

Andover trades with Barbados

Simon Bradstreet, as a trader, operated his Andover sawmill and engaged in the exchange of lumber with Barbados in return for West Indies goods, which he sold throughout Essex County. By 1646, Bradstreet made visits to Lynn, MA to oversee the shipping and delivery of his lumber. He recorded his time at Joseph Armitage's tavern, The Anchor, in Lynn, “to goodman Armitage, for beare [beer] and wyne [wine] att several times as I came by in the space of aboute 3 years, 4s 3d. May 15th ‘49. More for my man & horse, as he returned home the last years when I was a Commander, hee being deterred a sabbath day, 4s 8d, Simon Bradstreete". This record reveals a few interesting details. Firstly, it shows that Bradstreet purchased goods on credit for over three years, and only when Armitage sold the tavern did, he request payment. Secondly, there is no specific mention of rum or Kill-devil in the record, but given Lynn's status as a trading town, it is likely that rum was introduced early on. The exact timing of rum production is a topic of debate, but it is probable that by 1652, rum exports joined sugar and molasses from the West Indies. Thirdly, Bradstreet refers to "my man," who was likely his slave or indentured servant, as he is mentioned after his horse. Many affluent colonists owned slaves, although precise records of numbers are not available.

Bradstreet most likely traded for sugar, molasses, and later rum (Kill-Devil), supporting the rapid growth of Barbados in the mid-1650s with his lumber. Edmond Faulkner of Andover, who held a liquor license, probably served the Kill-Devil that Bradstreet brought back from Barbados in his establishment.

As trade demands increased, the need for roads became apparent. In 1647, individuals were appointed by the General Court to establish the "Way to Reading to Andover," "the road from Andivir to Haverhill," and "view the river" (referring to the Ipswich River). These early roads connected neighboring towns and rivers. Then, in 1653, the General Court ordered that representatives from Ipswich, Newbury, Rowley, and Andover select individuals to lay out the common highways between the towns. With improved roads, Andover became more accessible to other towns, including Haverhill along the Merrimack River, and to coastal towns such as Ipswich, Rowley, and Newbury. This facilitated trade with the crews of the thousands of ships navigating these routes.

The trade of rum to Boston or Newport, RI, was a thriving business. Livestock, lumber, and produce (including lumber traded by Simon Bradstreet from Andover) were sent south to Barbados, where "Good Rume and Mallasces... is most vendable heare," as written by a merchant to his agent in Barbados in 1660. Over 90% of rum exported from Barbados and Antigua, and 10% from other islands, was destined for mainland North America.

It is important to acknowledge that New England was also involved in the slave trade, transporting slaves from Africa to the West Indies. This triangular trade, involving cod from Newfoundland, slaves from Africa, rum from the West Indies, and livestock and lumber from New England, emerged during this early period. Boston and Newport played active roles in trade, including the trade of slaves. Although New England's participation in the slave trade was smaller compared to Charleston, South Carolina, it was nevertheless a significant aspect of the region's history. Boston and the rest of New England experienced growth in power and wealth as the "rum trade" expanded. By the 18th century, this newfound wealth would become a source of contention, eventually leading to the famous phrase "taxation without representation".

The birth of New England Rum

With the rise in the consumption of rum, we began to witness the implementation of more regulations. Acquiring a license to operate an ordinary establishment, which was previously a simple form-filling process, now required letters of recommendation after 1675. This creates a series of challenges.

As rum became more prevalent and professional brewers gained prominence, the production of home-brewed beer declined. Between 1665 and 1670, beer accounted for a high percentage of probate records in Essex County households, reaching 58%. However, after the surge in rum, that percentage dropped to 39% by 1680. This decline can be attributed to both decreased demand for beer and the emergence of new producers. Home brewers must have felt the impact on their income. (It is noteworthy that due the 1680’s is when Andover experiences its first murder, a new curfew, 2 new taverns, and numerous partitions over drunken conduct.)

By 1672, approximately 73% of Boston's ordinaries exclusively sold beer, while the remainder served a combination of beer, wine, cider, and/or rum. Although rum did not become legal in Boston until 1673, the city's trade with the West Indies ensured the availability of "kill-devil" (rum). By 1679, over 46% of ordinaries in Boston sold rum alongside beer. From that point onward, rum began to gain popularity, and by the turn of the century, New Englanders, including those in Essex County and Andover, consumed significant quantities of rum.

In the 1680, the density of ordinaries in Essex County varied widely. Salem, with approximately 80 residences, had only one ordinary, while Andover, with over 850 people, had one ordinary and one retailer. It is likely that both John Osgood (Innholder) and William Chandler were also serving beverages by 1680, but they obtained their licenses in 1686.

By 1684, the first rum distillery in North America was operational in Providence, RI. However, it wasn't until 1700 that North America's rum trade truly flourished. Immigrating distillers, increased availability of molasses, a robust trading fleet, and the growing slave trade to provide labor contributed to the rapid growth of distilleries. In 1688, Boston imported only 156,000 gallons of molasses (half of which was used for rum production), but by 1717, Boston alone produced 200,000 gallons of rum annually. By 1750, Boston boasted over 25 distilleries, with an additional 10 located outside of Boston in places like Watertown, Haverhill, Salem, Charlestown, and Medford.

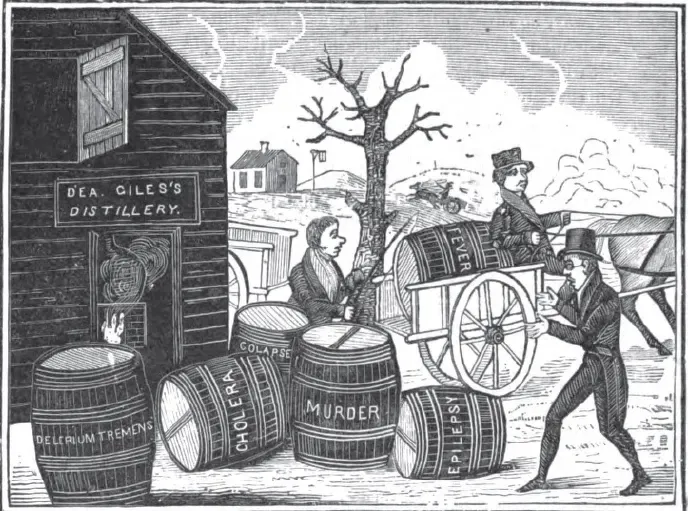

Despite the large number of distilleries, they primarily used cheap molasses and produced inexpensive rum. "New England rum" gained a reputation for being of lower quality compared to the well-regarded West Indian rum.

Early distilling encountered numerous challenges, ranging from the quality of equipment and the use of lead pipes to water quality, aging processes, and the skill of the distiller. It's safe to say that rum must have tasted quite terrible during those times. In fact, a visitor in 1651 described kill-devil as "a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor." The use of lead pipes carried the risk of a painful condition known as "the dry gripes," which involved excessive griping pains in the stomach and distended bowels, often caused by excessive wind. Many people frequently fell ill after consuming rum, experiencing severe stomach and intestinal issues. Interestingly, the remedy often involved using molasses as an enema. In those early days, rum was referred to as "Kill-Devil," a thick, black, and unpleasant liquid that varied in quality depending on the distiller's location. It's quite intriguing how rum's popularity continued to grow despite these challenges.

Symptoms of elevated lead levels resulting from the use of lead pipes include poor appetite, stomach aches, vomiting, constipation (rather than diarrhea), crankiness, loss of energy, anemia, headaches, and trouble sleeping. In severe cases, very high lead levels may lead to coma, convulsions, and even death.

By 1690, approximately 50% of all rum production occurred locally, and the first popular cocktail, Flip (a combination of rum, beer, and egg whites), became all the rage. While punch, mulled wine, and cider were also popular mixed drinks, the popularity of rum and Flip quickly overshadowed the demand for other beverages—except rum.

Andover: A Microcosm of Rum's Impact and Growth

Step into the bustling town of Andover in the 17th century, and you'll find yourself at the heart of a rapidly expanding rum culture. As a microcosm of this growth, Andover experienced both the benefits and the social challenges that came hand in hand with the rising popularity of rum.

With the increasing trade of rum from the West Indies, and Andover's lumber heading south, Andover witnessed a surge in wealth, and a population, once modest, grew to over 800 souls. Andover was truly on the rise.

However, alongside the prosperity, the arrival of rum brought its fair share of "social ills." By the 1680's, the impact of rum on Andover's society was evident in the rise of various issues, including curfews were implemented, the town faced petitions against rowdy taverns and the violent brawls that often-accompanied excessive drinking. It even had its first murder attributed to excessive drinking.

Andover would face the task of finding a balance between reaping the rewards of rum's economic potential and addressing the social issues that came with it. This delicate balancing act would shape the course of Andover's history in the years to come.

So next time you stroll through the historic streets of Andover, remember the role it played as a microcosm of rum's impact and growth. It serves as a reminder that every chapter in history has its triumphs and tribulations, and Andover's story is no exception.

Sources

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Cheever, Susan, Drinking in America, Our Secret History, Twelve, New York, New York, 2015.

Curtis, Wayne, And a Bottle of Rum, A History of the New World in Ten Cocktails, Broadway Books, New York, New York, 2006.

Earle, Alice Morse, Stage Coach and Tavern Days, The MacMillan Company, London, 1900.

Comments ()