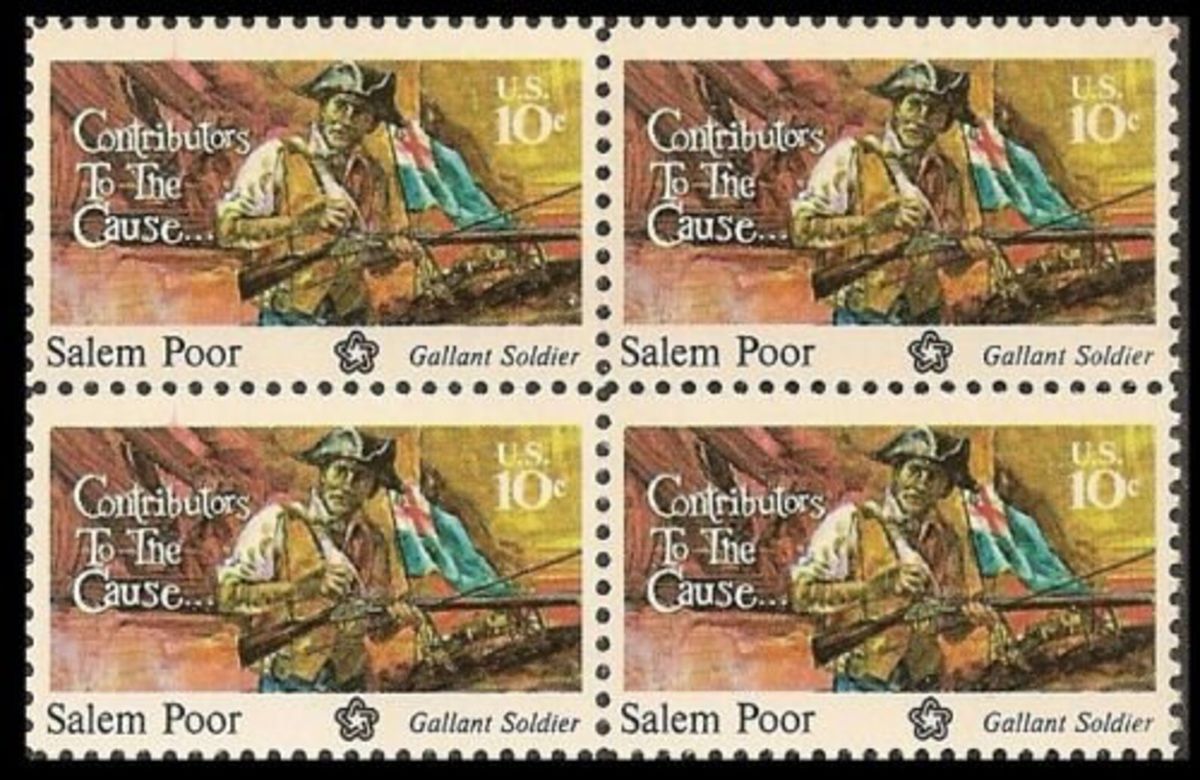

Salem Poor: Slave to War Hero

Salem Poor, a heroic figure of the Revolutionary War, was commemorated on a US postage stamp. His remarkable journey included rising from the bonds of slavery, though he ultimately passed away in modest circumstances.

Salem Poor's story begins when he was acquired by John and Rebecca Poor in Salem, Massachusetts, which is where he got his name. It remains uncertain whether he was brought to Salem on a slave ship or born there. According to legend, as an infant, Rebecca carried Salem to Andover perched on the bow of her saddle. In 1747, at the tender age of 3 or 4, he was baptized as the "boy, servant to John and Rebecca Poor" in Andover, Massachusetts, marking the beginning of his life as a slave in Andover.

Slavery in 18th C. Massachusetts

The history of slavery in Andover isn't well-documented, but recent efforts by the Andover Center for History and Culture have significantly improved our knowledge by creating a registry of known slaves. By 1754, Andover had a total of 42 black slaves, comprising 28 men and 14 women. While we have detailed studies on slavery in Boston, like The Negro at the Gate: Enslaved Labor in Eighteenth-Century Boston, by Jared Ross Hardesty, we can only speculate about what life was like for Salem Poor as a slave in Andover during the 1700s.

In Massachusetts, enslaved blacks were the primary source of bound labor and outnumbered other types, including apprentices, indentured servants, and Indigenous peoples. Boston's labor needs were unique, differing from other regions of the America’s where bound laborers were mainly involved in agriculture. The town's thriving mercantile economy depended on skilled workers capable of providing specialized services like shipbuilding (which involved around thirty different trades), blacksmithing, coopering, printing, and distilling. Owners often trained their slaves to expand their labor force and increase their value.

Slaves served in one of three ways: working directly for their master, being hired out, or setting the terms of their own employment. The most common arrangement was working directly for their master, with over 70% of female slaves serving as domestic servants. Although men had fewer restrictions within the home, they also often worked directly with or for their masters. Some even ran errands for their masters, as seen in tavern records like Simon Bradstreet's Man traveling to Lynn. Nevertheless, 27 percent (140 out of 518) of all males advertised for sale in Massachusetts between 1704 and 1781 possessed skills in domestic tasks such as gardening, stable work, and waiting tables.

"Hiring-out" was another way for slave owners to profit from their "investment". Owners would advertise available workers, and Bostonians in need of labor would post requests for hired slaves. The hiring process seemed informal, with few records surviving.

Although the evidence is limited and mostly circumstantial, there were instances where slaves found their own employment. Onesimus Mather, for instance, learned to read and write, and Cotton Mather rewarded him with "great Opportunities to get money for self."

As we can see, the experience of being a slave was fluid and heavily influenced by the needs and temperament of the owner. These historical records allow us to begin to understand what led Salem to eventually become a freed slave.

Poor’s Tavern

John Poor III, who happened to be Salem Poor's owner, was a fourth-generation Andover resident. By the mid-1700s, he had become a prominent landowner in what is now South Lawrence, Massachusetts, formerly known as Shawshin Fields. In addition to his large landholdings, John enjoyed a sterling reputation and served in various roles, including selectman. Nearby, the home of Timothy Poor, an innkeeper, also stood.

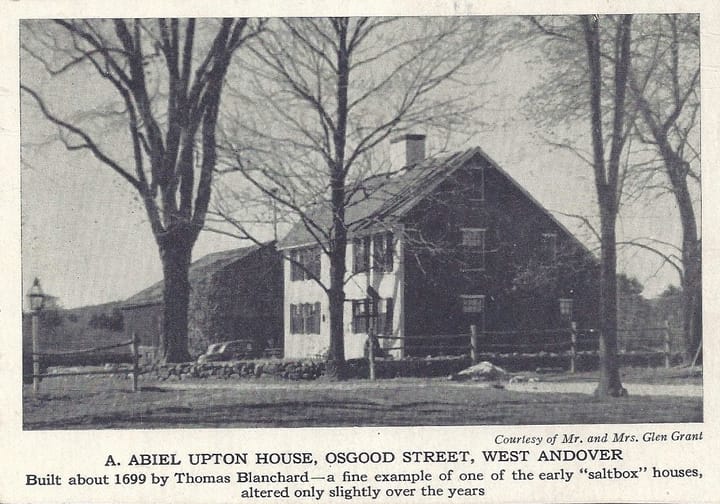

In the tradition of many tavern owners, running taverns seemed to run in the family. The Poore Tavern in Newbury, for example, was constructed back in 1642 and remarkably resembled the "Old Poor Homestead" of Enoch Poor.

Timothy Poor's inn, conveniently located at the corner of South Broadway and Andover Streets, was just a short distance from the ferry that crossed the Merrimack River to Haverhill. Although the exact establishment date remains unknown, it was in operation before the Revolutionary period. Being in close proximity to the ferry, this inn likely provided not only accommodations but also stable services, along with food and drinks. This route probably served as a post road to Haverhill, regularly bringing news from Boston. Locals would gather at the tavern to share and discuss the day's news over a few drinks.

Following the American Revolution, the Poor's Inn, became known as the "Shawsheen House," continued to operate with Ebenezer and Benjamin Poor as its proprietors.

Salem Poor’s freedom

How did Salem Poor manage to secure his freedom? The exact details remain elusive. However, what we do know is that around 1769, when Salem was roughly 25 years old, he took a significant step toward freedom by purchasing it from John Poor for £27, which would be equivalent to approximately $6,000 today. The question arises: How did Salem amass such a substantial sum of money? Could it be that John Poor, like Cotton Mather, allowed his slave to work and earn his own money? If that were the case, Timothy Poor's Inn would have been a plausible place for Salem to earn extra income, perhaps as a stable hand or by waiting on tables.

The Poor Inn serves as a logical setting where Salem could have expanded his understanding of the grievances against the British Parliament, which ultimately led to the Revolutionary War. Listening to the conversations of patrons while working at the inn would have provided him with valuable insights. It's worth noting that the Poor family was well-represented among the Patriots, so both at home and at the inn, Salem would have been immersed in discussions that deepened his comprehension of the unfolding issues.

In 1771, Salem Poor married another former slave, Nancy Parker, and the couple welcomed a child named Jonas. Notably, in 1774, during an Andover Town Meeting, a decision was made not to provide financial support to the wife and children (and it's possible there were more children) of Salem, who was still referred to as "the servant of John Poor III." This additional piece of information reinforces the notion that Salem lived in close proximity to the Poor family and was within earshot of the voices of the Revolution.

Battle of Bunker Hill

As a free man, Salem had certain expectations placed upon him, one of which was to take part in militia drills. These drills, held monthly, were essential for honing the skills required for military service. When the Revolution began, Salem answered the call and joined Captain Benjamin Ames' South Parish Company, consisting of 58 men, and served under the command of Col. Frye's Regiment.

On June 17, 1775, the Battle of Bunker Hill unfolded, with the Andover Regiment present on the battlefield. This battle was intense, resulting in the loss of three Andover men's lives and severe injuries to another seven. Salem Poor found himself right in the heart of the action, lending a helping hand to the wounded as they retreated. However, it was at this pivotal moment that Salem's life took a dramatic turn. He fired a final shot that proved fatal for British Army Lt. Col. James Abercrombie, cementing his status as a war hero.

The significance of Salem's heroic act is underscored by the fact that 13 officers later sent a petition to the General Court on December 5, 1775, which stated:

Salem Poor was the only soldier so honored. His service continued in 1776 under Captain Abram Tyler's company and served at Fort George. Later, he made the significant decision to re-enlist for three more years, dedicating his time to the cause at Saratoga. However, on July 10, 1775, George Washington ceased the recruitment of African Americans, eventually banning all black men from participating in the Continental Army by December. Salem, however, chose to remain, showcasing his unwavering commitment. In 1777–1778, he endured the harsh winter at Valley Forge and fought valiantly in the Battle of White Plains. Following this, Poor promptly re-enlisted in the militia, serving alongside Patriot forces until March 20, 1780, when he received his discharge in Providence, Rhode Island.

In that same year, Salem Poor married Mary Twing, a fellow former slave. They settled in Providence, where they were later ordered to leave, likely due to financial difficulties. In 1785, Poor publicly disavowed Mary's debts through a newspaper advertisement. Subsequently, he entered into marriage once more, this time with a white woman named Sarah Stevens in 1787. Their journey together saw them spending several weeks in a Boston Almshouse in 1793, and Poor faced a brief incarceration for breach of the peace in 1799. He married once again in 1801.

Salem Poor's life came to an end in a Boston Almshouse a few months after his final marriage. On February 5, 1802, the Boston Overseers of the Poor documented the burial of Salem Poor, noting that he was "...a negro man belonging to the Town of Andover."

Salem Poor's life was marked by tragedy, yet it was equally distinguished by his unwavering patriotism. While it's highly likely that the Poor Tavern played a significant role in his life, we may never know all the details. What we do know, however, is that he received recognition during his lifetime and again two centuries later for his acts of valor and commitment to his country.

Sources

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Dalton, Bill, Salem Poor's heroism and disappointing life, The Andover Townsman, Feb 7, 2013.

Hardesty, Jared Ross, The Negro at the Gate: Enslaved Labor in Eighteenth-Century Boston, The New England Quarterly, Vol. 87, No. 1, pp. 72-98, The New England Quarterly, Inc. 2014.

Lambert, David Allen, Salem Poor (1743/44-1802): A Forgotten Hero of Bunker Hill Rediscovered, New England Ancestors, pp40-41, Fall 2007.

Mofford, Juliet Haines, Andover Massachusetts: Historical Selection from Four Centuries, Merrimack Valley Preservation Press, 2004.

Comments ()