"Necessities of the Neighborhood"

How many houses extended hospitality to travelers along the road without a license? Considering the distance between houses and the time it took to travel, a welcoming stop along the way was necessary. These houses provided hospitality without a license and are truly forgotten taverns.

Many taverns began in this manner. It was common for homes to charge travelers and neighbors for drinks before obtaining a license. For instance, in 1680, John King of Salem expressed surprise at being indicted because he believed that having the "approbation of forty or fifty of the neighborhood to sell liquor by retail" was sufficient license. For three years, supported by local custom, he "supposed he was at liberty to supply the necessities of the neighborhood."

In the upcoming issues, I will spotlight these hospitable taverns.

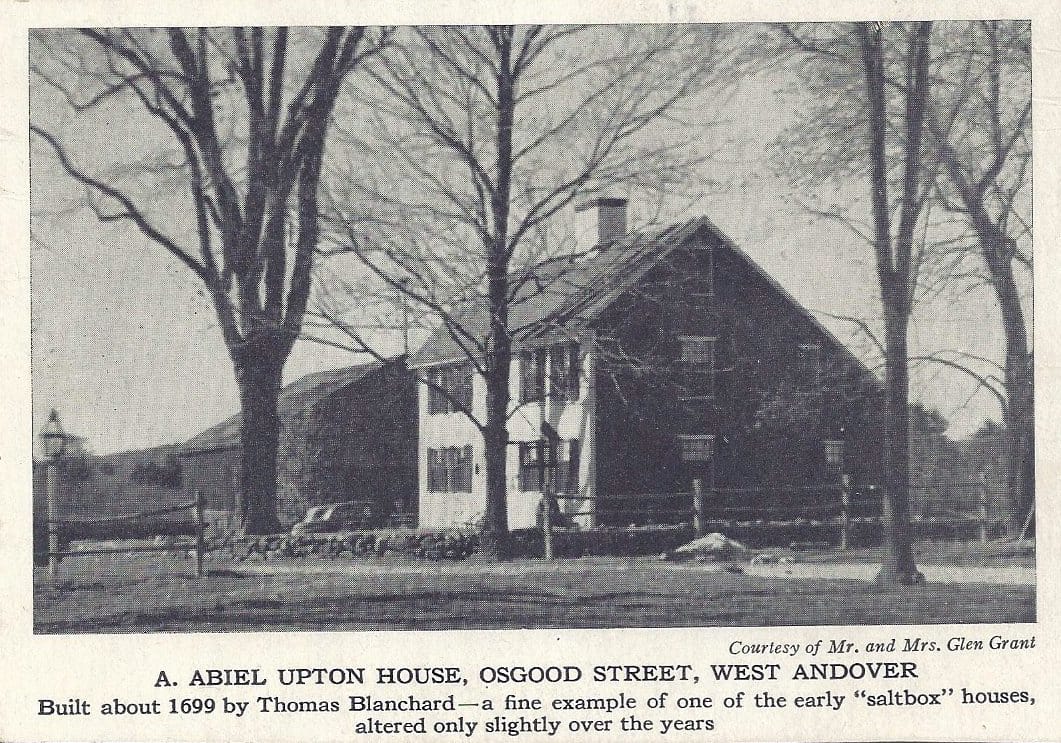

Blanchard-Upton House

Samuel Blanchard was born on August 6, 1629, in Hants, Penton Grafton, England, and was nearly 10 years old when he arrived in Boston on June 23, 1639, traveling with his parents from London.

Samuel’s father, Thomas, was born in France and migrated to England during the French Huguenot movement. There, he married Agnes and had four sons, along with an additional son born at sea, who sadly perished along with Agnes. Thomas and his surviving sons settled in Braintree and Malden. In February 1651, they purchased land and a house on the Mystic River side of Charlestown, where Thomas lived until his passing on May 21, 1654. Upon his death, Thomas bequeathed to Samuel “the sum of four score pounds, thirty of which were to be paid in cattle, ten pounds in corn, and ten pounds annually, in either cattle or corn, for four years.”

Samuel, a husbandman, served as a constable in Charlestown in 1657. He married Mary Sweetser on November 3, 1654, with whom he had six children. After Mary's passing, he married Hannah Doggett. Together, they had four children, all born in Charlestown: Thomas (born April 28, 1674), Jonathan “John” (born July 3, 1677), Samuel (born June 4, 1680), and Hannah (born September 26, 1681). By 1686, Samuel had relocated to Andover with his family from Charlestown, MA.

In Bailey’s Historical Sketches of Andover, there's a claim that Henry Jacques was an alias for Samuel Blanchard, but evidence supporting this is scarce. Henry Jacques (born 1619) was a housewright who worked in Newbury during the 1640s and migrated to Andover with the earliest settlers before 1646. Given Samuel’s funeral in 1707 and his recorded presence in Charlestown, it's highly improbable they were the same individual. Despite their French heritage and likely shared religious beliefs, there's little to suggest a connection beyond their profession. Interestingly, one of Samuel’s children, Joshua (born 1661), became a housewright and probably trained under Jacques, highlighting the intergenerational transmission of skills in this trade.

Samuel Blanchard acquired a significant amount of land on the west side of Andover as early as 1662 and, following tradition, allocated parcels to his children to establish homesteads. In 1699, he gifted 50 acres to his son, Thomas Blanchard, upon his marriage to Rose Holmes on March 22, 1698/9, and another 50 acres to his daughter, Hannah, upon her marriage to Stephen Osgood in the same year. These properties bordered Samuel’s land and were connected by what is now known as Osgood Street.

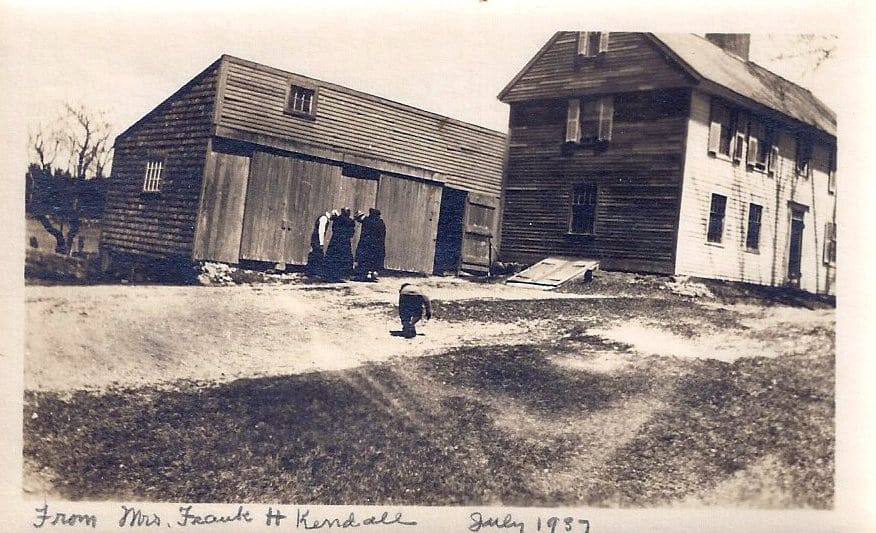

Thomas Blanchard builds his home

Thomas Blanchard enthusiastically embarked on constructing his new house, crafting a two-room home with one room positioned to the left of the entrance and chimney, and another room situated on the second floor. An expansive chimney on the east end graced the house, leading to a grand 10' wide fireplace in the spacious first-floor room. This inviting space also boasted "Indian Walls" — a brick barrier between the inner and outer sheathing, originally utilized for defense during early colonial days. (Brick in the walls also acted as fire stops). This ground-floor kitchen became a cherished spot to bask in the warmth of the fire.

As the family expanded, and prior to 1720, the house underwent expansion, gaining a matching east side and an integral salt-box roof.

An intriguing aspect of the construction is its adherence to French techniques. Given the Blanchards’ French connections and the presence of Henry Jacques, an active builder in Andover during the late 1600s, this architectural influence isn't unexpected. Furthermore, it sheds light on why Samuel Blanchard chose to own land situated far from South Parish Church and Andover Center.

Road to Tewksbury

Thomas' property lay along the Road to Tewksbury. This lost road extended from Osgood Street into the woods, connecting to the Old Stagecoach Road in Tewksbury, and is approximately 3.5 miles from the heart of South Parish Andover. This road presented numerous opportunities. Thomas, being a shoemaker, regularly received deliveries of leather for crafting shoes, while his finished products were collected and paid for. Additionally, about a quarter mile down the Road, Thomas operated a mill, likely a sawmill, which was supplied by a mill pond and springs across the Road from his house. These activities, along with other passing traffic, made Thomas Blanchard's home a frequent stop for travelers.

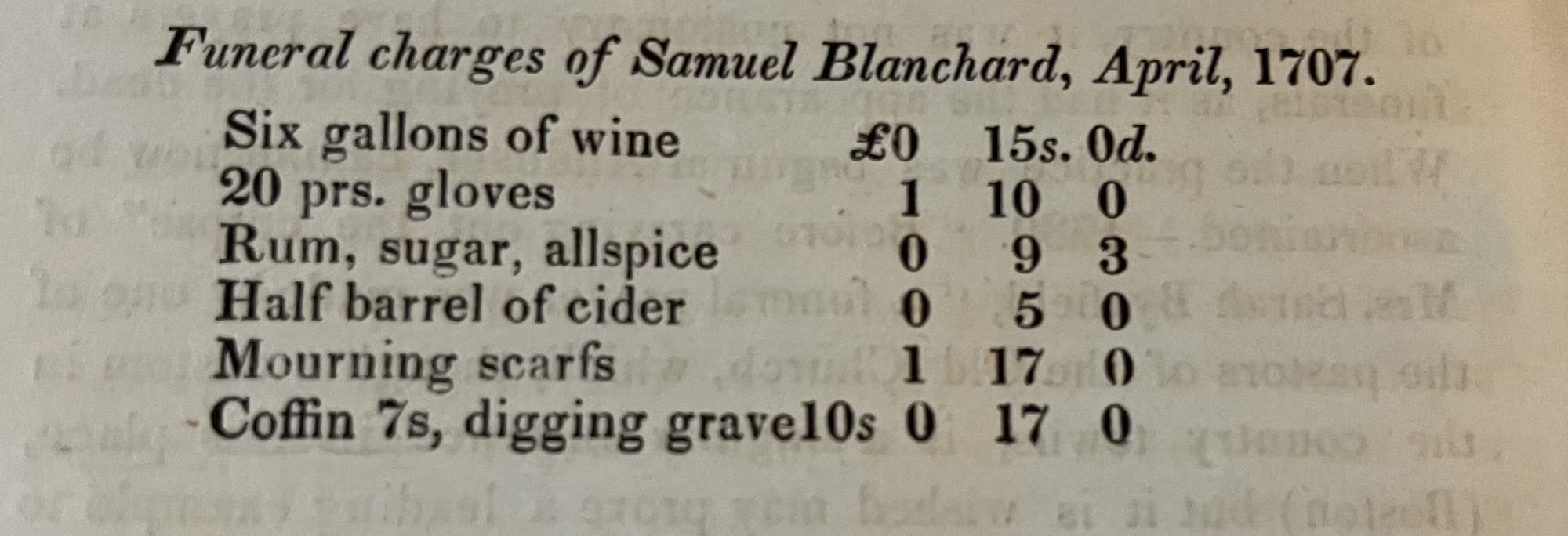

Guests stopping by frequently would naturally expect a refreshment. Much like today when hosting guests, a hospitable host offers something to drink. In the early 1700s, this practice included offerings like hard cider, beer, and perhaps even rum. Early settlers harbored concerns about drinking water purity, so cider was a staple in every household. Orchards were among the first crops planted, and each autumn, apples were pressed into cider and stored in basements. Similarly, beer was primarily brewed at home, with over 50% of households seeing women tending kettles of beer over the fire. Even well into the 1800s, cookbooks provided detailed instructions on brewing beer.

While there's no official record of the Blanchard House holding a tavern license, there are indications that it welcomed numerous guests with alcoholic beverages. Before 1740’s Thomas Blanchard’s closest neighbor was over two miles away. As William Chander highlighted in his tavern license petition, traveling 1-1/2 miles is too far for travelers without expecting a tavern. That was enough for Chandler to get licensed for the Horseshoe. Thomas Blanchard did not try to get licensed as a tavern, but as was the custom surely offered drinks to travelers.

How many other homes situated along commonly traveled roads also functioned as informal taverns, offering hospitality to travelers? Taverns were the focus of hospitality with or without a license.

Sources

Abbot, Abiel, History of Andover from its Settlement to 1829, Flagg and Gould, Andover, MA 1829.

Andover Historic Preservation Site, Welcome to the Andover Historic Preservation Web Site | Andover Historic Preservation (mhl.org).

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1880.

Comments ()